“Wherever truth can be found”

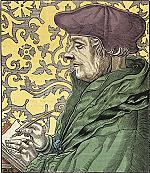

[Erasmus riding between Rotterdam and Basel. Louis van Roode, Holbeinhuis Mosaic, Coolsingel, Rotterdam—Sandra Fauconnier / [CC BY 4.0] Wikimedia]

CH: What do you most want people to understand about Erasmus as a humanist?

Ronald K. Rittgers: I teach a class called Faith and Folly: Christian Humanism in the Renaissance. We treat Erasmus as arguably the most famous Christian intellectual north of the Alps during his lifetime. I think what’s most important about Erasmus—and this is true of all the Christian humanists—is that he believed the gospel and was earnest about his life with Christ, and at the same time, he welcomed truth, goodness, beauty, justice, and virtue wherever they can be found—even outside of specifically Christian sources.

Most of the Protestant reformers were trained as humanists. After plague, war, and schism, the humanists wanted Europe and its church to be reborn. They wanted better editions of the church fathers’ writings and better editions of Scripture, but also better editions of non-Christian sources. Erasmus famously wrote in the Handbook of a Christian Soldier—when he’s talking about the necessity of reading ancient philosophy, especially Plato, to understand the Bible—“But let everything be related to Christ.”

Ancient Christian logos theologians (logos is the Greek word for “word” used in John 1 for Jesus) believed that Christians have a leg up on every other ancient philosophy because we have reason himself. We have the Word himself.

Erasmus was very consciously reappropriating that. There was this spirit of generosity that wherever there is truth, wherever there is wisdom, wherever there is virtue, it’s related to Christ. Therefore it is a gift for the Christian. There were tensions there, to be sure. Erasmus got into trouble for saying Socrates will probably be in heaven.

Erasmus was very influenced by the late medieval movement of spiritual renewal called devotio moderna: deeply heartfelt inward piety that produces the imitation of Christ. But he also wanted to read all kinds of people outside the Christian fold because he believed he could find wisdom there too. I think that’s a really interesting tension for a modern Christian to live in: being rooted in Christ, but being open to wherever God has placed goodness, truth, and wisdom for us to find.

CH: Erasmus traveled a lot. What was his role as a friend, networker, and influencer?

RKR: Erasmus was uniquely cosmopolitan in outlook among the humanists. Most of them were ardent nationalists, and Erasmus refused to be roped into any one national tradition—Dutch or otherwise. He had invitations to take up residence with all of the movers and shakers of his age; he’d visit for a while, but then he’d move on.

Wherever he could find worthy intellectual interlocutors who were deeply committed to spiritual renewal, that’s where he wanted to be—not just because he wanted to be with smart people, but because he wanted to transcend differences that separated people. He was not intimidated by the boundaries that other people set up.

On the other hand, Luther was frustrated with him because Erasmus wouldn’t take a position in their debate (see pp. 24–27). Luther referred to him as a slippery eel. Erasmus didn’t quite understand what was at stake pastorally in that whole debate. Luther’s existential pastoral sensibilities come through. Erasmus as pastor, I’m not so keen on; but Erasmus as a generous orthodox Christian theologian and intellectual—there’s a lot there. (To be fair Erasmus did author works of a pastoral nature, but they were not nearly as popular as Luther’s.)

CH: What about his ideas on education?

RKR: Some people criticize Erasmus as being too idealistic about education. He developed a whole curriculum for how everyone should be introduced to the “philosophy of Christ.” Given the literacy rates of the day (under 10 percent), which he knew full well, maybe he was a little out of touch with reality. But he did inspire a Protestant school in Nuremberg in 1526 that became a forerunner of the German gymnasium school system.

Was he out of touch or was he just ahead of his time? I think the final line of my lecture on Erasmus is that nobody followed the letter of his prescriptions, but his spirit lived on, which was entirely appropriate given his Neoplatonic leanings.

When my wife and I discussed sending our kids to college, I said I wanted them to have an education in Christian humanism. I want them to be able to encounter truth wherever it is. But I want them to be rooted in biblical theology. And that’s basically what Erasmus wanted, beginning with the Bible itself.

CH: Are there some areas where we shouldn’t listen to Erasmus?

RKR: The Neoplatonism thing can cut both ways. When there’s been a strict division between mind and body, as can happen in Neoplatonism, misogyny has often followed. We can question what role women played in Erasmus’s program for reform and what vision he had for the education of women.

Also the debate with Luther was an interesting intellectual question for him. He laid out the different views and asked: Why do we have to nail it down to one thing? For Luther people need to know what’s expected of them, if anything, in the life of salvation, because the peace of their conscience is at stake.

I think Erasmus was orthodox in his theology. But you can criticize his Christology for being too low and his human anthropology as being too high. He affirmed the necessity of grace in salvation, but sometimes he presented Christ primarily as a teacher of Christian virtue whom we can follow by the exercise of our (somewhat) free will.

He was so deeply concerned about the materialism and the superstition of a lot of late medieval piety that he was constantly trying to get people to look beyond it. But Christianity has a lot at stake in affirming the goodness of the material world—provisionally in this age, but still good.

When push came to shove, Erasmus said he agreed with the historical church about the Eucharist (see pp. 20–21), and he got upset when reforming Protestants saw him as advocating for a spiritual presence in the Eucharist rather than Jesus’s physical presence in the elements. He would say he’d never said that. But you can see why they concluded that he believed in a spiritual presence from his theology. CH

By Ronald K. Rittgers and the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #145 in 2022]

Ronald K. Rittgers is professor of the history of Christianity at Duke Divinity School. He is the author or editor of numerous books on the Reformation including A Widower’s Lament, The Reformation of the Keys, and The Reformation of Suffering. He spoke to us about the continuing relevance of Erasmus.Next articles

Erasmus: Recommended resources

Read more about the life of Erasmus and his role in sixteenth-century humanism and reform in these resources recommended by our authors and CH staff.

the authors and editorsIntroduction

Lewis called the Incarnation "the grand miracle"

Jennifer Woodruff Tait and Marjorie Lamp MeadIntroduction

Lent developed out of periods of prayer and fasting by new converts in the early church

Jennifer Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate