Colleagues and critics

[Sylvester van Parijs, Portrait of Mary of Hungary on horseback, 1538 to 1553. Antwerp, hand-colored woodcut—Rijksmuseum / [CC0] Wikimedia; NOTE anyone with definite knowledge of the meaning of the stick, please contact us.]

Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (c. 1450–1536)

Little information about Jacques Lefèvre’s early life is known apart from his birthplace of Étaples, France (hence the addition to his surname to differentiate him from a contemporary). By the time he entered the University of Paris to study for the bachelor of arts degree in the late 1470s, he was an ordained priest.

Around the age of 30, Lefèvre traveled to Italy and familiarized himself with Aristotle, Plato, and other classical thinkers. He became a devoted humanist and returned to the University of Paris to utilize classical teaching styles as a professor.

He later moved to the Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, where his former student Guillaume Briçonnet (c. 1472–1534) was abbot. There Lefèvre delved into deep study of the Bible. In his De Maria Magdalena et Triduo Christi Disceptatio (1517), Lefèvre contended against some medieval thinkers that Lazarus’s sister Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the woman who anointed Jesus’s feet were all different women. Extreme controversy ensued, but he continued working and writing. Erasmus was also critical of Lefèvre, particularly around the latter’s knowledge of Greek in his commentary on Paul’s epistles.

By 1523 Lefèvre was vicar general of now-Bishop Briçonnet’s church in Meaux. Within two years Franciscan friars suspected the clergy there of holding Protestant views—their diocesan reform had hints of “Lutheranism.” The resulting suppression of his works by the Parlement of Paris forced Lefèvre to flee France. He was only able to return under King Francis I’s protection. Later Lefèvre received the shelter of the king’s sister Marguerite de Navarre (1492–1549); he served as court chaplain and tutored her children and other young royals, living at court until his death.

Although he often courted controversy, Lefèvre always seemed more interested in teaching and learning than in theological debates. His piety astounded his contemporaries, with Martin Luther writing in 1517, “I am afraid Erasmus does not exalt Christ and God’s grace enough and in this he is much more ignorant than Lefèvre.”

Like Erasmus, Lefèvre remained a Roman Catholic dedicated to reform from within. One of those reforms included the availability of the Bible in the people’s own language, which he boldly declared in the introduction to his 1523 French translation of the four Gospels: “The Gospels are made available to you in the vernacular tongue from the Latin version that is read everywhere, without adding or removing anything, so that the simple members of Christ’s body may be as certain of the evangelical truth as those who have it in Latin.”

Johann Froben (c. 1460–1527)

Born in Hammelburg, Germany, Johann Froben went to university in Basel, after which he established a printing business in the city. Basel was quickly becoming a center of European printing through the established work of Johann Gutenberg’s former apprentices.

Froben developed a professional friendship with famous printer Johann Amerbach (1444–1514), whose son Bonifacius Amerbach was a professor in Basel; Froben eventually purchased Amerbach’s printing house in 1507. Froben desired to use his printing acumen to publish the works of the Greek fathers and joined with the older Amerbach and Johann Petri to print the collected works of Augustine.

Froben and Erasmus had both a deep friendship and a successful working relationship. Erasmus would stay with Froben’s family whenever in Basel, and Froben published many of Erasmus’s works. Between Froben and his son, the pair printed more than 200 of Erasmus’s writings and revisions.

Froben’s most famous printing was Novum Instrumentum Omne, Erasmus’s New Testament in Greek. Martin Luther consulted the second edition of the work in his own translation of the New Testament into colloquial German.

Froben also hired famous artist Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497–1543) to illustrate many of his texts, and the artist created Froben’s printer’s mark and painted a portrait of him circa 1522. Froben innovated Basel’s printing industry by using roman type, italics, and Greek fonts.

In 1527 Erasmus wrote a letter describing his grief over his great friend Froben’s death, arguing, “all the apostles of science ought to wear mourning.” In large part because of Froben’s skill, dedication, and innovation as a printer, Basel became the sixteenth-century center of the Swiss printing world, spreading ideas that would contribute to the Reformation.

John Colet (1467–1519)

Born the oldest son of Sir Henry Colet, who served twice as the lord mayor of London, John Colet graduated from Oxford in 1490. After becoming a rector, he traveled to France and Italy in 1493 to study law, patrology, and Greek for three years. Colet returned to England in 1496, was ordained two years later, and began lecturing at Oxford on the epistles of Paul. While a lecturer Colet invited fellow humanist Erasmus to visit him in England, where Erasmus watched Colet deftly shift from the old scholastic method of teaching to one that incorporated classical methods of instruction.

By 1504 Colet was appointed dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral, and five years later, after inheriting a great deal of money from his father, he founded St. Paul’s School—where boys could receive a Christian education. Colet later became chaplain to Henry VIII and preached at Thomas Wolsey’s ordination as cardinal.

Though some portrayed Colet as a closet or emerging Protestant, he remained a devoted priest who wanted to reform the Catholic Church from within. He believed that only by reading the Bible could one gain holiness, and he also attacked idolatry and abuses within the church. The bishop of London even accused Colet of heresy in 1512, although the charges were later dropped.

Colet wrote commentaries on Romans and Corinthians as well as treatises on the church and the sacraments. He also wrote a popular Latin grammar book with William Lilly (c. 1468–1522) and Erasmus. Erasmus wrote of his friend, “When I listen to Colet it seems to me that I am listening to Plato himself”—great praise from a fellow admirer of the classical philosophers.

Colet died in 1519 of the sweating sickness in London.

Johannes Oecolampadius (1482–1531)

Born in Germany into a well-off family, Oecolampadius went to Heidelberg University to study theology. He soon became a humanist interested in classical learning, Greek, and Hebrew. By 1515 he was cathedral preacher in Basel, and because of Oecolampadius’s deep knowledge of Greek, he became Erasmus’s assistant on the latter’s Greek translation of the New Testament. Oecolampadius continued his love for languages and theology by translating many Greek church fathers’ works.

Oecolampadius had an interest in the monastic life and joined the Brigittine monastery at Altomünster in 1520. He found his position there uncomfortable after his rejection of transubstantiation and his emphasis on the study of the Bible were revealed, and he left in 1522. Oecolampadius returned to Basel to teach at the university and preach at St. Martin’s Church. Not only did he depart from Catholic views of transubstantiation but also went so far as to join Zwingli in disagreeing with Luther’s view that the Eucharist contains Christ’s real presence.

Instead Oecolampadius advocated for a humanist understanding of the Greek New Testament: Jesus’s body and blood could be nothing more than symbolic. Luther and Oecolampadius debated one another on the meaning of the Eucharist in 1529 at the Colloquy of Marburg. The two camps divided their allegiance to either Luther’s side or Zwingli’s.

After Oecolampadius became Basel’s most celebrated preacher, speaking against Roman Catholic abuses and a literal interpretation of the Eucharist, the city of Basel officially adopted the views of the Protestant Reformation in 1529. Erasmus complained, “Oecolampadius is reigning here.”

Oecolampadius was relieved that the transfer was peaceful and involved no violence. Conflicts continued elsewhere as the Reformation spread, however, and Zwingli was killed during the Battle of Kappel in 1531. Oecolampadius, already struggling with his health, joined his friend and colleague in death one month later.

Bonifacius Amerbach (1495–1562)

The son of a Swiss printer (see p. 37), Bonifacius Amerbach studied law and classical antiquities in Basel and Freiburg. He then moved to Avignon, France, to study under Andreas Alciatus (1492–1550), or Alciat, a renowned Italian writer and lawyer. Amerbach received his doctorate in Avignon in 1525, thereafter teaching at the University of Basel.

As a student in Basel, Amerbach struck up a friendship with Hans Holbein the Younger, who painted a portrait of Amerbach in 1519; Holbein would go on to become a famed court painter to Henry VIII in 1535. During Reformation outbreaks of Bildersturm (image-storm, or iconoclasm) when Protestants destroyed religious art, Amerbach saved numerous Holbein paintings.

While in Freiburg, Amerbach befriended Erasmus, with whom he initially shared opposition to the views of the reformers. Amerbach was especially reluctant to accept Johannes Oecolampadius’s view on the Lord’s Supper—that Christ’s body is metaphorically, not literally, present with the bread. To maintain Amerbach’s professoriate, the University of Basel agreed that the professor could abstain from partaking in the Lord’s Supper.

In 1534 the city of Basel released a new confession for those who lived there to sign; this confession’s language on the Eucharist was vaguer, and the city council agreed with Amerbach that his views were not contrary to it. He became rector of the university in 1535, and immediately went to Freiburg to fetch Erasmus to help him. After Erasmus died in Basel in 1536, Amerbach became the heir of his estate, demonstrating how close their friendship had been.

Amerbach had tried to outrun the plague at various times in his life—first in 1521 and again in 1539—but his wife, Martha, and youngest daughter, Esther, died of the disease in 1541 and 1542. Amerbach lived another 20 years, retiring from teaching at the university in 1548.

Mary of Hungary (1505–1558)

Mary was the fifth child born to King Philip I and Queen Joanna of Castile. Mary’s mother, Joanna, was the sister of Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII’s first wife, and her grandfather was Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. Married in 1515 to King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia, she was crowned queen of Hungary six years later.

Her marriage was happy, and she mourned her husband’s death when he drowned during the Battle of Mohács against invading Ottomans. A Hungarian courtier wrote to Erasmus at the time that if Queen Mary “could only be changed into a king, our affairs would be in better shape.” Because she had no children, Mary’s reign as queen of Hungary ended at Louis II’s death; she vowed never to marry again.

Mary was interested in the writings of Luther and Erasmus. Both men wrote treatises for the young widow: Luther dedicated to her Four Comforting Psalms in 1526, and Erasmus wrote A Christian Widow to Mary in 1530. Regardless of her personal humanist and perhaps Protestant-leaning views, Mary acquiesced to the advocacy of Catholicism as the only true faith by her brother, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

After Mary served a short regency in Hungary, Charles V appointed her regent of the Netherlands; he needed trusted family members to help rule the many territories in his kingdom. An ardent opponent of Protestantism, Charles V forced Mary to discourage its spread throughout the Netherlands. She did not rule with a heavy hand toward Protestants, however, perhaps betraying her sympathies.

After Charles renounced his throne in favor of his son Philip, Mary also resigned after 27 years of service and moved to Castile. In a letter to her brother outlining her reasons for wishing to resign, she wrote, “a woman is never so much respected and feared as a man, whatever her position.” She died in Castile at age 53. CH

By Jennifer A. Boardman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #145 in 2022]

Jennifer A. Boardman is a freelance writer and editor. She holds a master of theological studies from Bethel Seminary with a concentration in Christian history.Next articles

“Wherever truth can be found”

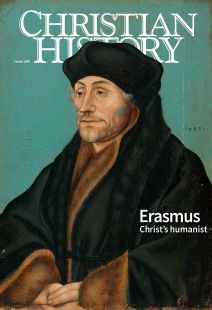

Ronald K. Rittgers and the editorsErasmus: Recommended resources

Read more about the life of Erasmus and his role in sixteenth-century humanism and reform in these resources recommended by our authors and CH staff.

the authors and editorsIntroduction

Lewis called the Incarnation "the grand miracle"

Jennifer Woodruff Tait and Marjorie Lamp MeadSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate