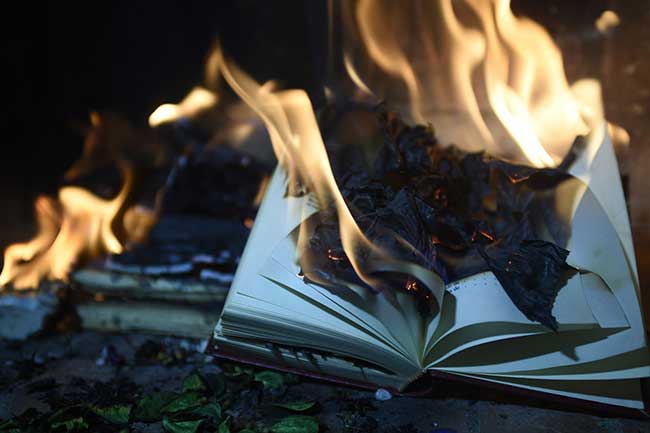

WHICH RELIGIOUS BOOKS WERE FIT ONLY TO BE BURNED IN RUSSIA?

[Above: a burning book, image by Rafael Juárez from Pixabay. Free for use under the Pixabay Content License]

LATE IN MAY 1998, a Russian paper, Nezavisimaia Gazeta, published a story about the burning of Christian books in Yekaterinburg, Russia. Yekaterinburg (also spelled Ekaterinburg) is not some minor outpost. Located in the Urals, it is one of Russia’s largest cities. Its hierarch is the third highest ranking bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church. In response to media questions, Boris Kosinsky, spokesman for Bishop Nikon of Yekaterinburg, denied the incident. He added “It is the bishop’s will and I cannot comment on it.”

When confronted shortly after the burning, Nikon claimed he only destroyed some magazines, not books. Witnesses became reluctant to talk. However, after almost a year, the book burning was established as fact before the Sacred Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church.

What had happened was this. On this day 5 May 1998, following a session of the ecclesiastical consistory of the Ekaterinburg diocese, Nikon called the school and ordered confiscation and destruction of certain works. Underlings confiscated books from seminary students and burned them in a large iron crate in the seminary courtyard. Among the confiscated texts were publications of Alexander Schmemann, John Meyendorff, Nikolai Afanasiev, and Alexander Men. Many Orthodox believers consider these writers liberal and even heretical. However, Fr. Alexander Schmemann’s works had been widely used by the Russian Orthodox Church and published with authoritative approval, and Alexander Men was often called the “Russian C.S. Lewis” and a “one-man antidote to decades of Marxist propaganda.”

Men’s spirit can be seen in his prayer,

“Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, despair, lust of power, and idle talk. But give rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to Thy servant. Yea, O Lord and King, Grant me to see my own transgressions, and not to judge my brother, For blessed art Thou, unto ages of ages. Amen.”

In addition to burning the books, Nikon also defrocked the priest Oleg Vokhmianin for life when he refused to renounce the writings. The official charge included the following wording:

“For persistence in error and allegiance to new doctrines which contradict the traditions of the holy fathers and do not have the approval of the plenitude of the Orthodox church, and for persistent refusal to aid in the exposure of dangerous and heretical notions, which was unequivocally expressed in front of the ruling bishop and members of the ecclesiastical consistory, from 5 May 1998 you are forbidden to perform your clerical ministry for the rest of your life, without the right of giving blessing and wearing the cross and vestments.”

However, Moscow authorities soon overrode the hierarch in this matter. Father Oleg Vokhmianin was restored to the priesthood a month later. By contrast, in 1999, the Russian Orthodox Church “retired” Bishop Nikon, then aged just 39. The reason given was that he had provoked divisions among the clergy and believers. However, corruption was involved. More than fifty priests had complained he demanded large fees to resolve administrative disputes, was drunken, and openly homosexual.

Although the book-burning was generally deplored in the press, not all Orthodox were sure it was a bad thing. Lay Christians called into a local radio station to agree with the burning. So did many priests. One of them, David Mozer, called the book-burning “a visible icon, a method of teaching that is vivid and emotional.” Archbishop Chrysostomos wrote a letter after the burning. In it he objected to Schmemann having questioned the beneficial impact of Constantine’s conversion and his claiming there had been changes under Constantine in the forms and beliefs of the Orthodox Church. This statement was not surprising. Two years earlier he had described Schmemann and Meyendorff as “the most perverted theologians who have spoken within the Orthodox Church” because of their ecumenical spirit and their regard for western scholarship.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more about the writers mentioned in the article and the religious climate in Orthodox Russia, consult Christian History #146, Christ and Culture in Russia