SATTIANADEN MADE HISTORY FOR INDIA'S TAMIL LUTHERANS

[Modern Palayamkottai (Palamcottah) Public Domain / Wikipedia]

IN 1778, Lutheran missionary Christian Frederick Swartz visited Palamcottah, India, to preside over a wedding and baptize some children. A Brahman widow requested baptism, but as she was living out of wedlock with a British captain, Swartz refused her request. Years later, the captain died, leaving her well off. In 1783 she traveled to Tanjore and again requested baptism, which now was granted. Swartz gave her the baptismal name Clorinda. That same year Clorinda built a church in Palamcottah. Swartz staffed it as he was able. But as time went on, lacking European missionaries, he turned to an able Indian helper. Sattianaden Pillai (also transliterated as Sattyanadan or Satyanathan) had converted from Hinduism and become a catechist.

On this day, 26 December 1790, Swartz and his fellow-missionaries ordained Sattianaden the first Tamil missionary of the Lutheran Church in India. Swartz described the event:

After the first hymn had been sung, I addressed [Sattianaden] from 1 Timothy 4:16, “Take heed to yourself,” &c. I then received his promise to discharge his office according to the instructions that had been given him. Each of us then blessed him, and commended him to the grace of God. Mr. Jaenicke and Mr. Kohlhoff next addressed him in a short exhortation. Finally, I turned to the congregation, and asked them whether, as we had now set him apart as Native Pastor, and were about to give him his written vocation and instructions, they would engage to acknowledge him as their appointed teacher, and yield obedience to him? They all answered, “We will.” On this, I gave him his Call and Instruction; and Royappen, the Native Preacher, concluded with prayer.

Sattianaden then preached from Ezekiel 33:11: As I live, says the Lord, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked. . . . His sermon so impressed leaders of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel they printed it and called for men like Sattianadan to be appointed as suffragan bishops. The sermon asked to whom the offer of divine mercy was made [everyone], how to obtain the blessing [by repentance and faith], and what blessings would follow [eternal life in all its riches]: “Let us therefore be persuaded no longer to continue in the practice of sin. . . . [A]nd endeavor to grow in grace and in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ, by our frequent addresses to him, and daily surrender of ourselves into his hands.” Swartz’s account of the ordination wrapped up on a note of praise:

[A]nd as soon as [Sattianaden] had concluded, received the Holy Supper with us. This was a sacred and most delightful day to us all. Should I not sing to my God? The name of the Lord be humbly praised for all His undeserved mercy! May He begin anew to bless us and the congregation, and graciously grant that through this our brother many souls may be brought to Christ! Amen.

The prayer that through “this our brother” many might be saved was certainly answered, for by the end of 1802 Sattianaden had baptized about 2,600 new believers.

—Dan Graves

----- ------ -----

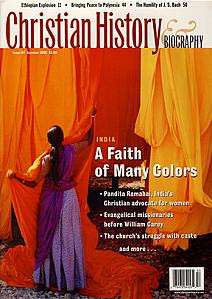

For more on Christianity in India, read Christian History 87: Christianity in India, a Faith of Many Colors