THE RISE AND CONFLICTS OF HINCMAR, ARCHBISHOP OF RHIEMS

[Representation of Hincmar at Rheims—G069 / [CC BY-00] Wikimedia File:Reims (51) Saint-Rémi Baie 208-2.jpg]

ON THIS DAY, 3 MAY 845, Rothad, bishop of Soissons, consecrated Hincmar as archbishop of Rheims. This was significant because it moved Hincmar into a powerful position from which he frequently intervened in ninth-century European political and ecclesiastical affairs.

Born around 806—probably in Northern France—Hincmar studied at the abbey of Saint-Denis, Paris, obtaining the grounding in canon law and theology that enabled him to become an advisor to kings. In 834 he became an advisor to Louis I the Pious, and in 840 to Charles the Bald, who awarded him the abbeys of Nôtre-Dame at Compiègne and Saint-Germer-de-Fly.

Hincmar’s subsequent rise to archbishop was not without conflict. Ebbo, the former archbishop of Rheims, had been twice deposed by synods. However, Ebbo had the backing of Emperor Lothar I, who was hostile to Hincmar because Hincmar adhered faithfully to Lothar’s rivals, first Louis the Pious and then Charles the Bald. Upon taking office, Hincmar nullified Ebbo’s consecration of priests, and Ebbo appealed to Pope Sergius II, asking for his see back. The pope upheld Hincmar’s possession of the see. Pope Leo IV then conferred the pallium on Hincmar—a white woolen band worn by popes and archbishops to symbolize their full and legitimate episcopal authority.

As archbishop, Hincmar was in the thick of many controversies, usually about his own authority or the power of the royal personages whom he supported. These controversies were complex and are only touched upon here in the simplest outline.

When Lothar II sought to divorce his wife, Hincmar forbade it and wrote De divortio Lotharii et Teutbergae (On the Divorce of Lothar and Teutberga) strongly affirming the Christian position against divorce.

Later Rothad, bishop of Soissons, deprived a priest of his powers. Hincmar argued that as a suffragan bishop (subordinate to Hincmar) Rothad did not have the legal right. Pope Nicholas I, the Great, sided with Rothad. The trial cited decretals (decrees) that Hincmar suggested might be forgeries. They were, but not until the twelfth century did scholars begin seriously questioning them, and not until the seventeenth century was the extent of the forgery conclusively established. They are known today as the False Decretals. Meanwhile, the affair prompted Hincmar to write a book on his own ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Following Lothar’s death, Hincmar successfully maneuvered to get Charles the Bald crowned king despite Pope Adrian II’s objections. In subsequent conflicts, Hincmar actively organized opposition to Louis the German, Charles’s rival.

Hincmar’s most famous controversy was over predestination. He wrote against the view that God chose some people in advance for hell, and said we choose our own destiny. God’s foreknowledge does not compel us to sin, for God is never the author of sin. Hincmar also defended the doctrine of the Trinity in De una et non trina deitate (On One and Not a Threefold Deity).

Hincmar also opposed Pope John VIII when he felt John’s legate to Germany and Gaul intruded on his [Hincmar’s] prerogatives. To uphold his position, he wrote a life of Saint Remigius, making false claims about Rheims’ supremacy over other churches during Remigius's life.

His blessing for the eulogiae (bread left over from Communion) shows his Trinitarianism and his belief in the power of the blessed loaf. It went like this:

O Lord, holy Father, almighty, and eternal God, be pleased to bless this bread with Thy holy and spiritual blessing, that it may be to all who receive it with faith, reverence, and thanksgiving, health both of mind and body, and a safeguard against all diseases, and all the wiles of every foe; through our Lord Jesus Christ, Thy Son, the Bread of Life, Who came down from Heaven and giveth salvation to the world, and liveth and reigneth with Thee, God, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, forever. Amen.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

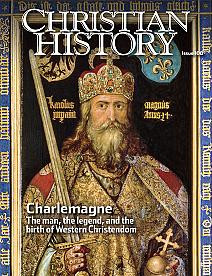

For more on the culture and political climate of that era, read Christian History #108, Charlemagne