Louis de Berquin Rejected a Compromise that Would Have Saved His Life

Louis de Berquin (left) is released from prison by John de la Barre

ONE of the earliest Protestant martyrs of France had the backing of King Francis I and his sister Marguerite. Ultimately, however, that was not sufficient to save him.

Louis de Berquin belonged to a noble family. Coming to Paris in 1512 to study, he met Christian humanists such as Jacques Lefevre de Etaples who wanted to reform the Catholic Church from within. William Farel, who would become the reformer of Switzerland, and Louis de Berquin listened to Lefevre with respect. “Christians,” said Lefevre to his students, “are those only who love Jesus Christ and His word.” They also listened to Erasmus, who pointed out the abuses of the church in witty writings. Berquin eventually opened correspondence with him.

Although Berquin agreed with much that Luther taught when the German reformer rose to prominence, he disliked his coarseness of speech. All the same he translated Luther’s De votis monasticis (On monastic vows) into French along with several tracts by Erasmus.

In 1523, the doctors of the Sorbonne declared some of Berquin’s writings to be heretical. He was tried before the French Parliament and imprisoned. King Francis I ordered him set free a few days later.

But in 1525 the king became a prisoner in Madrid, Spain. Parliament could safely disregard him and pursue Berquin’s case again. He was ordered to keep silent and remain on his estate near Abbeville. Berquin, however, felt that truth must be spoken and continued to call for reforms. Parliament burned his books and threw him into prison again. Only the intervention of the king’s sister, Marguerite of Valois, saved Berquin’s life.

Although Erasmus urged him to follow a safe course, Berquin refused to be silent. He replied to Erasmus, “Beneath the cloak of religion the priests conceal the vilest passions, the most corrupt morals, and the most scandalous infidelity. It is necessary to rend the veil which covers them, and boldly bring an accusation of impiety against the Sorbonne, Rome, and all their flunkies.”

In 1529, with the king away, Parliament tried Berquin again. Things looked bad for him. Marguerite, who loved learning and was both tolerant and brave, appealed to the king on Berquin’s behalf: “I, for the last time, very humbly make you a request; it is that you will be pleased to have pity upon poor Berquin, whom I know to be suffering for nothing other than loving the word of God and obeying yours.”

On this day 16 April 1529, Parliament brought Berquin into court at noon and read his sentence to him. He was condemned to make a public renunciation by walking bare-headed to the Place de Greve with a lighted candle in his hand, where he was to watch while his books were burned. He was then to proceed to the Church of Notre Dame and do penance “to God and his glorious mother, the Virgin.” After that his tongue was to be pierced, he was to be taken back to prison and shut up for life with neither books to read, nor pen and ink to write.

Berquin appealed to the king. When Parliament demanded Berquin fulfill his sentence that afternoon, he said, “I would rather endure death than give my approval, even by silence only, to condemnation of the truth.”

Afraid that the king would once again interpose on behalf of the scholar, Parliament brought Berquin out of prison the next day, 17 April 1529, and burned him at the stake as a heretic. One of the officials present at the execution, who was no friend of the Reformation, solemnly stated, “I never saw any one die more Christianly.”

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

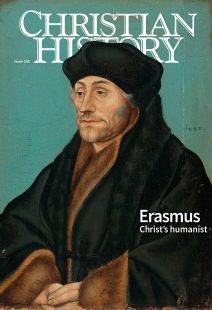

For more on the reforms inspired by Erasmus, see Christian History #145, Erasmus: Christ's humanist