KIMBANGU RAISED UP A CHURCH AND BECAME A NATIONAL HERO

[Above: Detail from view of the temple at Nkamba in 2018—Ratelki Amerique / [CC-BY-SA 4.0] Wikimedia File:NKAMBA 2018.jpg]

SIMON KIMBANGU heard a voice saying: “I am Christ, my servants are unfaithful. I have chosen you to bear witness before your brethren and to convert them. Tend my flock.” Kimbangu protested that he was untrained; and he fled the call, going to work in oil fields at Leopoldville (Kinsasha). His plea was not entirely true: he had studied and taught for years at a Baptist school.

After two years, Kimbangu yielded to God’s call and returned to his home village, Nkamba. “Throw away your fetishes,” he preached, “and put your confidence in the one and all-powerful God. Repent and believe that God is offering you salvation through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ.” After a woman was healed through his ministry on April 6, 1921 (which became the official date of the foundation of the Kimbanguist church), crowds flocked to hear him. More people were healed through Kimbangu and a child was restored to life. The movement’s spread accelerated, attracting hundreds of thousands of followers in just a few months. It seemed God cared for black Africans after all! The Congolese threw away their fetishes and embraced forms and teachings of Christianity.

Congo’s Belgian administrators became alarmed. Workers were leaving their jobs to go hear Kimbangu, disrupting both government and trade. Colonial authorities feared that the religious crowds might become mobs bent on overturning the government. As a precaution, they posted machine guns around Leopoldville. In June, they summoned mission leaders and pressed them to condemn Kimbangu. The Protestants were for lenient measures but the Catholic Redemptorist Fathers called for brutal suppression. A military unit attempted to arrest Kimbangu on June 6, but he fled with his assistants and with his eldest son, Charles Kisolokele.

For the next five months, Kimbangu trained disciples in secret. However, in September, declaring that God ordered him to give himself up, he returned to Nkamba, preaching openly that his followers should persevere, show courage, and practice nonviolence. Arrested, he offered no resistance. His disciples sang hymns as he was led away in shackles. At his hearing, which took place without witnesses or a defense counsel, Judge de Rossi asked, “Do you know that you have organized a plot against the colonial government, considering whites as enemies?”

Kimbangu rejected the charge. “I have not organized any movement against whites neither [against] the government. I was simply preaching the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

On 3 October 1921, the judge sentenced him to a beating and death. Authorities in Leopoldville administered one-hundred and twenty lashes. However, King Albert I of Belgium commuted the death penalty to life imprisonment, heeding the pleas of enlightened civil servants and Protestant missionaries.

Immediately the Belgians unleashed terrible persecution on Kimbanguists, killing tens of thousands and deporting a hundred thousand more to concentration camps. This, however, had the unintended consequence of spreading the religious movement even faster, because the deported believers carried its message with them. Soon after Kimbangu’s arrest, the army destroyed Nkamba to prevent a Kimbangu cult from emerging there. Nevertheless, Kimbangu’s impoverished wife lived secretly among the ruins, and her husband’s followers visited her there, revering even the water in which she bathed.

The imprisoned Kimbangu was enveloped with an aura of heroism. The prison director recommended his release in 1935, citing his good behavior. Colonial authorities and the Roman Catholic archbishop opposed this, so Kimbangu remained imprisoned. Apparently, he was not passive, however. A murderer in the prison, who later became a Protestant minister, claimed that, in violation of rules against sharing food, Kimbangu divided his meat and distributed it among other inmates. He then saluted the warden, and returned to his cell. With such stories swirling around him, he became a symbol of Congolese nationalism.

Kimbangu died in prison on this day, 12 October 1951. His son, Charles, attempted to keep the Kimbanguists focused. However, many religious and cult leaders sprang up, claiming to act in the power and authority of Kimbangu. False doctrines permeated many of these movements. Some claimed Kimbangu was Christ reincarnated and that his three sons represented the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit of the Christian Trinity. They taught doctrines foreign to Kimbangu. In 1967, Rev. James Bertsche, a Mennonite missionary, attempted to set the record straight:

Never, either before or after his imprisonment, did Simon Kimbangu lead people to believe that he regarded himself as anything whatsoever but a Christian whom God had called to preach the Word of Life to his People.

Kimbangu’s sons guided their father’s outlawed movement as best they could under threat of a fate similar to his. The church insisted on a strict moral code that set it apart from the old pagan lifestyle. In 1959, Congo’s civil authorities finally recognized the church. Ten years later, the Church of Jesus Christ on Earth Through the Prophet Simon Kimbangu became the first independent African church to attain full membership in the World Council of Churches. By 2005, it had around eight million adherents and was famed for its care of its members.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

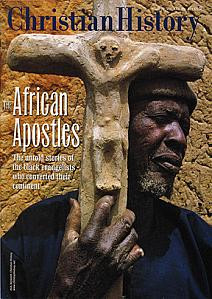

For more on Kimbangu, read "The People’s Prophet" in Christian History #79, African Apostles: Black Evangelists in Africa