JESUITS: FROM POST-REFORMATION RENEWAL TO SUPPRESSION TO THE PAPACY

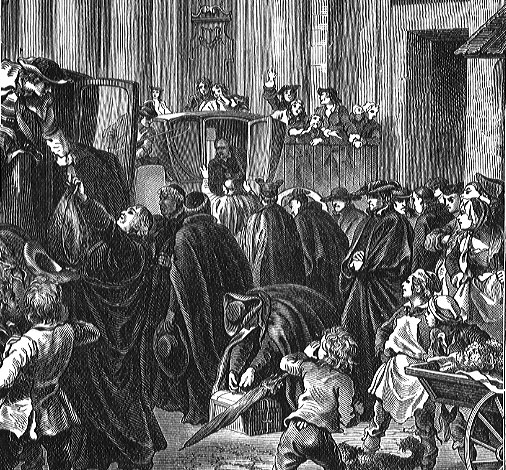

[Above: Jesuits expelled from Spain. Ridpath. Cyclopedia of Universal History. 1890. public domain]

DURING THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY, the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) spread throughout Europe. Founded in 1540, the order vowed to do the bidding of popes. It became famous for its far-flung missions and its innovative educational methods. On the good side, Jesuits founded hundreds of schools and protected the rights of indigenous people in Latin America. But many Jesuits also subverted governments and incited persecution of Protestants.

Some universities, cities, and states resisted the society. They complained about it to parliaments, kings, and popes. In 1565, an Austrian assembly demanded its banishment from Germany and Hungary. Antwerp expelled the society in 1578 because it refused to abide by a treaty.

After Jesuits plotted to assassinate her, Elizabeth I of England issued an order against them in 1591. In 1597, Henry IV of France restricted them because they tried to take his life and to undermine peace with Protestants. Elizabeth’s successor, James I, laid out a detailed case against the society in 1604.

In 1603, the Parliament of Paris noted that Jesuits were troublemakers. “When the King of Spain usurped the government of Portugal, all the Religious Orders adhered firmly to their King, the Jesuits excepted, who deserted him, and were the cause of two thousand deaths, for which they obtained a special Bull of Absolution.”

The uneasy relationship between Jesuits and Catholic nations continued into the following century. Portugal expelled the Jesuits in 1759 and France in 1764. On this day, 2 April 1767, authorities throughout Spain opened sealed copies of a letter from their sovereign, Charles III. The next morning, they arrested six thousand Jesuits, loaded them on ships, and sent them to Italy. Charles had grown alarmed at Jesuit wealth and power. He may have believed they were preparing to overthrow his government. He also expelled the society from his South American territories and from Naples.

Because Jesuits had always returned after banishment, European leaders demanded a permanent solution. Pope Clement XIV abolished the society in 1773. Jesuits went undercover or took refuge in Prussia and in Russia.

Pope Pius VII restored the society in 1814. He needed help against Napoleon who had humiliated and imprisoned him. The restored Jesuits lobbied for the 1870 decree of papal infallibility.

In the twentieth century, many Jesuits incorporated secular humanism or Marxism into their theologies. They ignored or defied popes who resisted the trend. They butted heads with John Paul II who opposed communism. Yet in 2013 an Argentine Jesuit, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, became Pope Francis I. The society had come a long way since its suppression.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more about the Jesuits, their founder, and their ups and downs, watch Pioneers Of The Spirit: Ignatius Loyola

and read relevant passages in Christian History #122, The Catholic Reformation