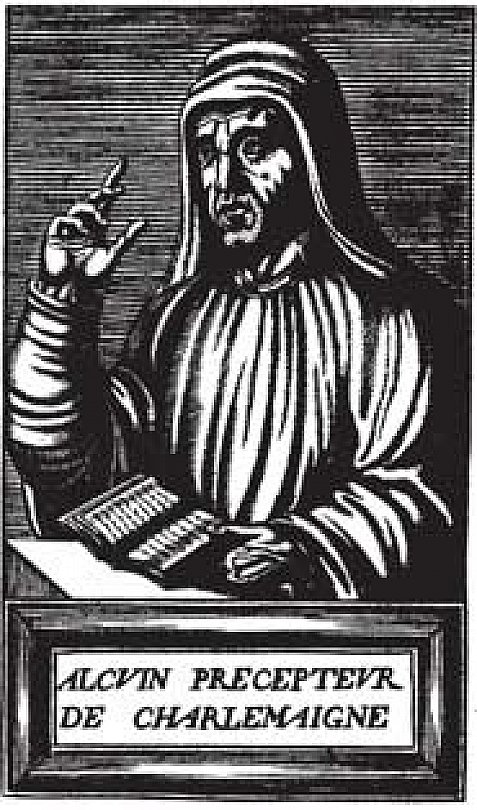

Alcuin the Educator Was a Friend of a Great Emperor

Alcuin was the leading educator in Charlemagne's empire.

N THIS DAY, 19 May 804, Alcuin died in the monastery of Tours in Gaul. Although English-born, he had allowed Charlemagne to persuade him to come to his court. In this way, Alcuin became the leading educator of the Franks.

Alcuin trained at York to become a teacher. The cathedral church there possessed one of the best schools and one of the largest libraries in Europe. He had risen to a position of leadership and was entrusted with important tasks. One such task was to obtain from Rome the pallium (a cloth that symbolized Roman approval) for York’s new archbishop. On his way home, he met Charlemagne in Parma (in modern Italy), and the great king invited him to join him in restoring learning and correcting the immorality of the clergy.

Although not able to yield to the request at that moment, Alcuin soon did join Charlemagne’s court. He advised the king, tutored his children, educated promising students, wrote books on morals, oversaw the copying of rare and precious texts that he placed in libraries around the kingdom, and gained fame and power. Manuscripts copied under Alcuin’s headship were renowned for their calligraphy, known as “Carolingian Miniscule” because the letters were smaller than those employed in the past.

When Alcuin finally returned to England, he did not stay long. Political conditions had deteriorated in Northumbria, and Viking invasions threatened the future of his homeland. When Charlemagne urgently requested he return to deal with two serious theological problems, the scholar agreed. First, some bishops near Spain had developed a theory that Jesus was not the begotten Son of God, but rather adopted into the Godhead. Alcuin exerted all his energy to refute this heresy and saw it condemned by the Council of Frankfurt in 794.

The second issue involved the veneration of images (mainly icons, or flat paintings). The Second Council of Nicaea (787) proclaimed that icons could be venerated but not worshipped, while prohibiting veneration of sculpture as “sensual.” Pope Hadrian I agreed with the council. When the decrees came to Charlemagne’s attention, possibly in a translation which erroneously indicated that Christians should give images the same honor they did to the Trinity, he asked Alcuin and other court theologians to refute the practice, which he regarded as the adoration that belongs to God alone. The resulting argument acknowledged that images were educationally useful but denied they should be “adored.” This opinion was confirmed at the Council of Frankfort with Hadrian’s representatives present.

Alcuin also pleaded with Charlemagne not to force conversion to Christianity on the Saxons. He suggested the king send holy monks and bishops among them instead to win their assent to Christianity by persuasion. Unfortunately, Charlemagne rejected this good advice, and the Saxons retaliated with war and slaughter.

Charlemagne put Alcuin in charge of the monastery school of St. Martin in Tours, where many pupils came to learn under him. One of his most notable students was the encyclopedia-writer and theologian Rhabanus Maurus. Late in life, upholding the pride of his monastery against Theodulf of Orleans, Alcuin disobeyed a direct command from Charlemagne to hand over an escaped criminal priest to Theodulf. Charlemagne rebuked Alcuin sternly for his disobedience. Already old and sick, Alcuin felt betrayed. He soon died. In the interim, he wrote a lengthy epitaph for himself, which included the lines:

What now I am, thou soon shalt be. Decay

Hath left no vestige of each futile aim,

Save dust and ashes to the worms a prey.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

Christian History #108, Charlemagne is devoted entirely to Charlemagne and his times.

Christian History #139, Hallowed Halls tells more about the rise of Christian education.