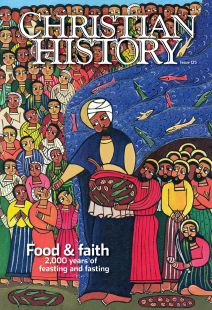

What would Jesus buy?

Your breakfast today: a bowl of cereal, a bagel, or perhaps a fruit and yogurt smoothie. Your breakfast 250 years ago: porridge, brown bread or hotcakes, and a mug of cider or beer. What happened in between to transform the American diet? It had to do with sickness, health, and God.

Your breakfast today: a bowl of cereal, a bagel, or perhaps a fruit and yogurt smoothie. Your breakfast 250 years ago: porridge, brown bread or hotcakes, and a mug of cider or beer. What happened in between to transform the American diet? It had to do with sickness, health, and God.

Early Americans were often sick. A 1793 yellow fever epidemic spread through Philadelphia, killed 5,000 people, infected Alexander Hamilton (he recovered), and shut down the national government. Abigail Adams had rheumatic fever as a child. George Washington had smallpox, suffered from attacks of dysentery, and lost a brother to tuberculosis. Ben Franklin lost a son to smallpox.

As the population of the nation increased from 3.9 million in 1790 to 23 million by 1850, so did the effects of disease: outbreaks of tuberculosis, diphtheria, cholera, pneumonia, malaria, typhoid, and yellow fever. Approaches to disease prevention varied wildly: Washington was bled for his dysentery, a practice that contributed to his death in 1799. And, to avoid smallpox, many Americans received live inoculations. People began to explore the role diet played in keeping healthy and preventing disease; and they often connected this to their faith.

vegetarian vision

Some of the earliest connections arose outside orthodox Christianity from Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), a Swedish engineer and scientist, who began to experience dreams and visions at age 53. They led him to proclaim a new revelation for the church that (among other things) forbade both meat and alcohol. Joseph Smith would later express a similar “Word of Wisdom” for the Mormons (Latter-day Saints).

Several Swedenborgian groups established congregations in the United States, and Swedenborg’s most dedicated disciple may have been John Chapman (1774–1845), known more familiarly as Johnny Appleseed. Chapman traveled through Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana establishing apple nurseries. He sold saplings to newly arrived settlers who were anxious to trim the growing time from seed to fruit-bearing apple trees.

Known for his gregarious nature and unorthodox religious views, Chapman acted as a Swedenborgian missionary. His self-denial fit his church’s emphasis on vegetarianism and temperance, and the iconic image of Johnny Appleseed in ragged clothes and bare feet may be more portrait than caricature.

Meanwhile, at the turn of the nineteenth century, Oliver Evans (1755–1819) had revolutionized the milling industry by improving the traditional mill. His inventions made the process less labor intensive, reduced waste and cross-contamination, and produced a finer flour. Americans had relied on mills to process hard wheat for home-baked bread. The cheaper, finer flour produced by new mills meant a softer loaf of bread; consumers turned to buying bread instead of making it at home. Later flour would even be bleached, as white flour was more attractive to consumers and had a longer shelf life.

Many Christians began to question the value of these advancements. In 1817 William Metcalfe (1788–1862) led his Bible Christian Church to migrate from England to Philadelphia. The BCC had been established in 1809 by William Cowherd near Manchester, England; it split from nearby Swedenborgians but kept prohibitions against eating meat and drinking alcohol.

In Philadelphia Metcalfe actively promoted pacifism, temperance, abolitionism, and vegetarianism. Like many Christian vegetarians, he taught that Christ himself was a vegetarian. The message wasn’t widely applauded, but his efforts brought him in contact with vegetarians from more orthodox traditions. One was William Alcott (1798–1859), a Christian medical doctor known for writing the first American vegetarian cookbook as well as various articles on “Christian physiology.” (Alcott’s close friend and second cousin Amos Bronson Alcott was the father of Louisa May Alcott of Little Women fame.)

Metcalfe may also have met Sylvester Graham (1794–1851), a Presbyterian minister in Philadelphia originally interested in the message of temperance. His reading led Graham to conclude that diet greatly affects health and that chemical additives are dangerous. In the Old Testament, Graham found Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden eating the perfect diet, which was, of course, vegetarian. He was particularly interested in promoting old-fashioned brown bread:

She who loves her husband and her children as woman ought to love, and . . . perceives the relations between the dietetic habits and physical and moral condition of her loved ones, and justly appreciates the importance of good bread to their physical and moral welfare—she alone . . . [is] a perfect bread-maker.

Graham flour and crackers were developed by bakers marketing to Grahamites. The bland cracker supposedly lessened the urge for “self-pollution,” a euphemism for masturbation. Graham spread his message in print in On Self-Pollution (1834), A Treatise on Bread and Breadmaking (1837), and A Lecture to Young Men on Chastity (1837). Foreshadowing the sophisticated marketing strategies of generations of diet gurus, he even published a book of testimonials.

In 1829 a cholera epidemic broke out in Europe. Graham told his audiences that the diet he described would prevent them from catching cholera. Critics blasted Graham in the newspapers, saying that a vegetarian diet would leave people weak, but those who had taken his advice and survived the epidemic testified to his diet’s effectiveness, thus increasing his popularity. In 1850 Graham joined William Alcott, William Metcalfe, and Russel Trall to establish the American Vegetarian Society in New York City.

cornflakes for God

In 1852 Joseph Bates, tireless evangelist of Seventh-day Adventism (see “The sacred duty,” p. 40), baptized John P. Kellogg, the father of John Harvey “J. H.” Kellogg (1852–1943) and Will Keith “W. K.” Kellogg (1860–1951), in Battle Creek, Michigan. Battle Creek would eventually become the Adventist headquarters, and doctor J. H. and marketer W. K. would remain prominent in the movement.

The Adventists established the Western Health Reform Institute in Battle Creek in 1866 as a place to encourage the sick to become well on Adventist principles. When J. H. completed his medical training, Ellen and James White asked him to serve as the institute’s medical director. He held the role until his death 67 years later, even though he was “dis-fellowshipped” from the SDA church in 1907.

J. H. believed strongly in the Adventist approach to wellness. Patients at the Battle Creek Medical and Surgical Sanitarium (Kellogg changed the name) were encouraged to consume lots of water, get plenty of sunshine, exercise, and eat a bland, low-fat diet. The Kellogg brothers shared with their predecessors the idea that a rich, flavorful diet excited the passions and led to spiritual and moral weakness.

In 1894 W. K. and J. H. developed a way to bake whole grains into flakes. The original creation was a wheat flake called Granose, soon followed by grain-based coffee substitutes, granola bars, and various roasted grain concoctions.

One of the patients who tried these early breakfast cereals was C. W. Post. Suffering from a series of stress-related breakdowns, Post went to Battle Creek for a cure. He left with the idea of developing and marketing his own breakfast cereals, which he began to do in 1895. The first was a “cereal beverage” called Postum; then came Grape Nuts and Post Toasties, a form of cornflakes originally called Elijah’s Manna from 1 Kings 17. (This was not the last time the Old Testament would inspire health food. In 1964 Christian natural foods grocer Max Torres began Food for Life, which still markets baked goods based on Ezekiel 4:9 and Genesis 1:29.)

Meanwhile the Kellogg brothers established the Sanitas Food Company in 1897 and began actively producing and marketing cornflakes. Religious convictions had little to do with the wave of consumers who turned to this new breakfast diet. It was clever advertising that convinced many of the health benefits and convenience. “You could simply pour breakfast out of a box,” historian Howard Markel said. “Even dad could make breakfast now.”

To make cornflakes more attractive to consumers, W. K. wanted to add sugar to the recipe. John Harvey disagreed—the addition of sugar ran counter to his entire philosophy. In 1906 they parted ways, and W. K. founded the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company. Two lawsuits later in 1922, W. K.’s company was renamed the Kellogg Cereal Company.

The sanitarium was eventually sold, and the Kellogg brothers never reconciled. (Supposedly J. H. wrote an apologetic letter to his brother on his deathbed, but John’s secretary found it too abject and never sent it.) Even so, along with Chapman, Metcalfe, Alcott, and Graham, the Kellogg brothers’ faith had remade the American breakfast table. CH

By Matt Forster

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #125 in 2018]

Matt Forster is a freelance author living in Clarkston, Michigan, and a frequent contributor to Christian History.Next articles

Food in Christian history: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you understand the story of food and faith.

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate