Welcoming the Stranger

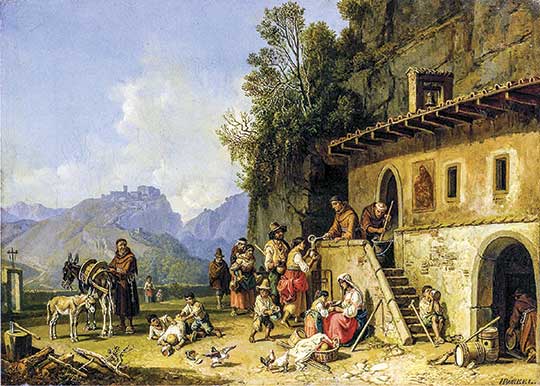

The Roman Empire was in trouble by the time of Benedict of Nursia (480–547), who founded 12 monasteries and left us his Rule as a guidebook for monastic life. The Goth Alaric had invaded in 400, followed by Attila the Hun in midcentury. Later Geiseric, king of the Vandals, pillaged his way through Italy leaving economic devastation. Benedict’s communities were islands of peace in the midst of a collapsing empire plagued by war, disease, and hunger.

Benedict’s holy charisma attracted those from all walks of life—shepherds, peasants, pagans, monks, nobility, and even royalty. His monasteries took in high-born and farmer; native and immigrant; educated and illiterate; young, middle-aged, and old. In the midst of violence, chaos, and impoverishment, Benedict chose to embrace strangers.

In his biography of Benedict, Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) recounted an incident that perfectly illuminates this, involving a monk-gardener, formerly a Goth who marauded through fifth- and sixth-century Italy. Gregory described this Goth as “poor in spirit,” perhaps indicating a background as a lowly soldier bullied by a sharp-tongued superior officer or a servant beaten regularly with a stick.

Whatever the monk’s former life, he panicked while clearing a thicket of thorns when the blade of his scythe detached, flew through the air, and disappeared into a lake. When Abbot Benedict heard of his monk’s predicament, he did not send a messenger to admonish or punish; instead, he interrupted his day to visit the distraught Goth. He retrieved and fixed the scythe miraculously, then handed it back to the frightened man, saying, “Here. Take your tool. All is well. Go back to work, but don’t be sad anymore. Stop worrying.”

Benedict’s actions epitomize the gentle spirit that would suffuse his famous Rule. In fact Christians have a long history of hosting strangers—and feeding them. The Old Testament instructs, “You shall love the stranger, for you were once strangers in the land of Egypt” (Deut. 10:19), and Jesus teaches this generosity as the essential nature of love: “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink. . . .

[As] you did it to one of the least of these . . . you did it to me” (Matt. 25:35, 40). As Augustine pointed out, “the stranger” is actually our “companion” on our communal earthly journey, for “we are all strangers.”

Even today food remains the soul of Benedictine hospitality. Benedictine sister Joan Chittister pointed out that monastic hospitality “bakes fresh bread daily and . . . open[s] a soup kitchen and a food bank and a food pantry” because that creates a real and sacred connection, in fact the “bread and butter” of Benedictines.

The Latin for “stranger,” hospes, which gives us hospitality and host, can also mean “guest.” Later “host” came to mean “enemy” and “army” (because armies devour things and people); but in hospital, hospice, and hostel, we witness caring for sick, dying, or sojourning strangers as the essence of hospitality’s gracious spirit. Since the 1300s host has also meant the “body of Christ” in the Eucharistic bread, that ultimate form of sustenance (see “Everyday substances, heavenly gifts,” pp. 27–31).

Benedict adopted this hospitality as central to his monastic vision, and chapter 53 of his Rule anchors this signature trait of accepting the stranger as God: “All guests who present themselves are to be welcomed as Christ, for he himself will say: I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” God, he knew, might show up poor, dirty, helpless, and from a country other than the one he called home.

By Carmen Acevedo Butcher

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #125 in 2018]

Carmen Acevedo Butcher is a lecturer at the University of California at Berkeley and the author of Man of Blessing: A Life of St. Benedict.Next articles

Baptists, Did you know?

Baptists “churching themselves,” founding schools, joining the army, and climbing trees

The editor and various contributors.Editor’s note: Baptists in America

Graham’s crusades and King’s struggles are seen as bigger than any one denomination. . . . a lot of Baptist stories are like that.

Jennifer Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate