Thinking long thoughts

“WHAT ELSE CAN ONE DO when he is alone in a narrow jail cell, other than write long letters, think long thoughts and pray long prayers?”

These words from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” (1963) might have been penned by any number of imprisoned Christians since the time of the apostle Paul. Innumerable letters, thoughts, prayers, poems, hymns, and novels have been composed under some of the worst conditions possible—many, like King’s letter, becoming classics that continue to exhort, comfort, and inspire readers today.

Perhaps the earliest and most esteemed writings from an imprisoned Christ-follower are Paul’s prison epistles: Ephesians, Colossians, Philippians, and Philemon (p. 10). They exemplify several common themes of Christian prison writings: Paul recorded his own devotional musings, used his situation as a prisoner to establish his spiritual authority, and offered comfort and exhortation. Similar testimonies from prison abound during the period of Roman persecution, perhaps none more famous than the first Christian writing we have by a woman outside the Bible—the “Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas” (p. 14).

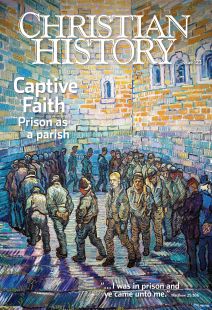

Luther translating the Bible while in captivity. D’Aubigne, Historic Scenes in the Life of Martin Luther. Illustrated by P.H. Labouchere. London: Day and Son, Limited, 1806.

Time to write long books

Several centuries later Roman philosopher, scholar, and statesman Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (c. 480–524) was imprisoned on charges of treason against the Ostrogoth king Theodoric. Against his master Boethius supported the Roman senate; also, Theodoric was an Arian while Boethius believed in the orthodox view of the Trinity. (Theodoric feared Trinitarians would unite against him with orthodox Easterners.)

In the year of imprisonment leading up to his execution in 524, Boethius wrote The Consolation of Philosophy, which would become one of the most influential texts in medieval and early modern Europe. Faced with his own dramatic reversal of fortune, Boethius crafted a dialogue in poetry and prose between himself and Lady Philosophy, seeking comfort amid the paradoxes of human will, fickle fate, divine providence, and mortal suffering.

Among the many inspired by Boethius was Thomas More (1478–1535). The influence of Consolation of Philosophy is apparent in More’s own Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation (1534). Like Boethius Thomas More wrote his Dialogue while imprisoned and awaiting execution (in his case in the Tower of London).

More, a staunch Roman Catholic, had refused to placate Henry VIII by signing the Act of Succession when Henry desired to divorce Catherine of Aragon and establish himself as the head of the Church of England. Like Boethius he explored the spiritual benefits of tribulation and found his source of consolation in an eternal perspective. Rather than drawing attention to his imprisonment, however, More created an impression of the commonality of suffering—in prison or out.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

One of the most famous prison classics is The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). Its author, John Bunyan (1628–1688), was arrested in 1661 for preaching; authorities feared nonconformists like Bunyan were stirring up rebellion against Charles II and cast suspicion on any group gatherings. During the 12 years he spent in a Bedford jail, anxiety for his wife and children and fears about the state of his own soul plagued Bunyan. Taking Paul as his model, he found comfort in the grace of God and came to regard suffering as an opportunity to identify with Christ, receive spiritual nourishment, and serve as a witness. Bunyan probably wrote the bulk of The Pilgrim’s Progress while he was in prison, though it was not published until after his release. According to some reckonings, only the Bible has sold more printed copies.

If these walls could sing

Others crafted poems and music in their cells. One, Theodulph (750–821), bishop of Orleans, was theological adviser to Charlemagne. Deposed in 818 by Charlemagne’s son, Louis I the Pious, for suspected conspiracy in a revolt, Theodulph was confined in a monastery in Angers (in western France) until his death. While there he wrote the lyrics to “All Glory, Laud, and Honor,” a hymn of praise still widely sung (though now generally in English rather than Latin and with fewer than the original 39 verses).

Centuries later John of the Cross (1542–1591), a mystic theologian, priest, and associate of Teresa of Ávila, was imprisoned for nine months in Toledo in the 1570s by an opposing church faction. Soon after his escape, he composed his now-famous “Cántico Espiritual” (“Spiritual Canticle”), possibly begun in prison.

And only a few decades later, the Tower of London housed poet and Jesuit priest Robert Southwell (c. 1561–1595), who ministered to English Catholics, largely in secret, until he was betrayed and imprisoned in 1592. In the three years before his execution for treason, he was tortured multiple times. Nevertheless he continued to write poetry, including a lyrical expression of Peter’s remorse following his denial of Christ. A collection of his poems, Saint Peter’s Complaint, with Other Poems (1595), was published shortly after his death.

Instrumental music, too, came from prison terms. Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) crafted his Quartet for the End of Time in 1940, while a prisoner of war in the Stalag VIII-A camp in Görlitz, Germany. The eight movements reflect themes and images from Revelation. He recalled the performance later: “The Stalag was buried in snow. We were 30,000 prisoners (French for the most part, with a few Poles and Belgians). The four musicians played on broken instruments.”

Some significant editions and translations of the Bible also developed in prison. Pamphilus of Caesarea (c. 240–310), a Christian scholar and priest, curated an extensive library and directed a theological school in Caesarea, Palestine. During the persecution of pagan Roman emperor Maximinus, Pamphilus was arrested, tortured, and executed.

During his two years of imprisonment, he continued his work editing the Septuagint (a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible). His famous library was destroyed in the seventh century, but not before serving as an important source for many scholars.

Over a thousand years later, following his excommunication and refusal to recant at the famous Diet of Worms in May 1521, Martin Luther spent 10 months hiding disguised and under a pseudonym in Castle Wartburg. Frustrated by the imposed solitude and excessive leisure, he suffered physical ills and apparent spiritual attacks. But they seemed to resolve when he began the absorbing work of translating the New Testament in October 1521.

Working from the original Greek, Luther completed it in 11 weeks; it was published in September 1522. Luther’s was not the first German translation of Scripture, but his mastery of the language resulted in a text written for ordinary people. Its popularity shaped the evolution of the German language.

Flowing with justice and mercy

Many prisoners have served as advocates for social reform. Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498) of Florence, a Dominican monk, lecturer, student, and ascetic, had established an impressive democratic government, but his abrasive and scathing critiques of Pope Alexander VI and other corrupt clergy earned him political and religious enemies.

Savonarola was arrested, suffered multiple “trials” under torture, and was hanged and burned for schism and heresy in May 1498. A number of prison writings have been inaccurately attributed to him, but one, at least, is almost certainly his: the “Exposition and Meditation on the Psalm ‘Miserere’ [51]” expresses profound spiritual sorrow at his failings and identifies his sole refuge in God.

William Penn (1644–1718), the eldest son of an English admiral, was raised Anglican. However in his early twenties, he joined the Quakers; his enthusiasm for his newfound faith led to his imprisonment in the Tower of London in 1668. There he wrote No Cross, No Crown (1669), eloquently presenting Quaker ideals of self-denial, pacifism, and social reform. Released in 1669 he went on to lead an eventful political and religious life (see CH issue 117).

German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers from Prison (1951) were compiled from his writings made between 1943 and 1945 (prior to his execution by the Nazi regime for his role in the plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler). In them he spoke against the Nazi regime and described the horrors of his imprisonment.

Richard Wurmbrand (1909–2001) spent 11 years imprisoned in Romania for refusing to endorse the Communist Party. His wife, Sabina, also suffered in prison. After his ransom by Western churches, Wurmbrand testified before the US Senate, showing his scars as an appeal to the free people of America not to support his oppressors. The Wurmbrands went on to found the Voice of the Martyrs in 1967, the same year Richard released his classic Tortured for Christ.

Novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008), a Soviet army captain enthusiastic about Communist ideals, was accused of anti-Stalin conspiracy in 1945 and spent the next eight years as a political prisoner. In 1952 he underwent emergency cancer surgery by a doctor who shared his own conversion to Christianity. The next day, the doctor was mysteriously bludgeoned to death. The experience inspired in Solzhenitsyn a new and deep awareness of God and of life.

Nine years after his 1953 release, Solzhenitsyn published One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962), based on his own experiences in the gulag. The bluntly honest book caused an uproar in Russia; his works, though officially banned, were widely circulated. Solzhenitsyn’s masterpiece, The Gulag Archipelago, critiques the prison camp system and the Soviet Union. Initially circulated clandestinely in manuscript form, it was officially published in 1973, after which Solzhenitsyn was deported. It has since been published in hundreds of editions and dozens of languages.

New Christian Charles Colson, formerly President Nixon’s top aide and “hatchet man,” experienced a crisis in conscience and spiritual conviction in 1974. Colson voluntarily pleaded guilty to Watergate-related charges and served a seven-month prison term. His memoir, Born Again (1976), relates his political experiences and his spiritual rebirth in prison.

Marching from jail

But perhaps no prison work is as well known as a statement for justice than the letter with which we began. In April 1963 an important desegregation campaign planned for the Easter season was faltering, so Martin Luther King Jr. decided to get himself arrested by ignoring a court directive against holding marches.

While in prison King penned his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in response to eight local clergymen who had called him and his colleagues extremists. In answer to the accusation, King affirmed his commitment to love and justice and aligned himself with other “creative extremists”: Paul, Martin Luther, John Bunyan. He exhorted the church to “recapture the sacrificial spirit” of early Christians who “rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed.” CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #123 Captive Faith. Read it in context here!

By Catherine Barnett

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #123 in 2017]

Catherine Barnett is adult and young adult services librarian in the Chillicothe Public Library District in Chillicothe, Illinois.Next articles

Paradoxes of prison

For some prisoners, the plunge into the depths became a step heavenward.

Dan GravesChristian History Timeline: Crime and punishment

Prisons, prison ministries, and Christians

the editorsPrison as a parish: Christian responses

How Christians have tried to reform the justice system and minister to prisoners

Todd V. CioffiSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate