The things that are Caesar’s

THE PHARISEES expected to hang Jesus on the horns of a dilemma—God or Caesar? Sacred or secular? Or in our terms, church or state? They inquired: “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not?” After examining a coin bearing the emperor’s image, Jesus resolved the dilemma: “Give, then, to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Matt. 22:17–21). In just a few words, Jesus distinguished God and Caesar, yet commanded obedience to them both.

[Forty Martyrs of Sebaste. Wikimedia: Andreas Praefke]

Two kingdoms

After Jesus’ death and Resurrection, as Christianity moved into the uttermost parts of the empire, the church wrestled with its ultimate allegiance to God and its lesser loyalty to the state. What did it mean for a Christian to be both a resident of the Roman Empire and a citizen of the Kingdom of God? The apostles gave different answers at different times.

During the early decades of church expansion, Roman authorities viewed Christianity as a sub-sect of Judaism, which was a legal religion. In 57 AD, basking in the protection of the civil government, Paul wrote to instruct the church in Rome: “Let everyone submit to the governing authorities, since there is no authority except from God, and the authorities that exist are instituted by God” (Rom. 13:1; 1 Tim. 2:1–2; Tit. 3:1). Even during the unsettled years before Nero’s persecution, Peter sent a letter from Rome to a group of exiles in Asia Minor (now Turkey), urging them: “Fear God. Honor the Emperor” (1 Pet. 2:17).

In spite of these expressions of loyalty, both Peter and Paul are traditionally said to have died martyrs’ deaths during Nero’s persecution from 64 to 68. About three decades later, Emperor Domitian instigated the second round of imperial persecution, most severe in Rome and in Asia Minor. The apostle John fell victim and was exiled to Patmos, an island off the coast of Ephesus. During these troubled times, he recorded the Book of Revelation, expressing a much different attitude toward government.

John used apocalyptic language that could be interpreted to refer to the Roman Empire, or to any government opposed to God. In Revelation John saw such governing authority as a beast that blasphemes against God and makes war on his people (Rev. 13:1–10), or a harlot from which “a voice from heaven said: ‘Come out of her, my people’” (Rev. 18:4). Paul advocated for submission to the state; John for separation from it.

The early church maintained these dual views of the state as expressed by the apostles. In the year of Domitian’s death, Bishop Clement of Rome wrote a letter to the Corinthian church. He began with a reference to the recent persecution: “the sudden and successive calamitous events which have happened to us.” In the same letter, however, he modeled for the Corinthian Christians a prayer for the government:

Make us obedient both to your almighty and glorious name and to all who rule and govern us on earth. For you, Master, in your supreme and inexpressible might have given them their sovereign authority that we may know the honor and glory given to them by you and be subject to them, in nothing resisting your will. Grant to them, Lord, health, peace, harmony, and security that they may administer the government you have given them without offense.

Honoring the emperor

Clement’s prayer for the governing authorities, expressed even in the context of persecution, exemplifies most Christians’ attitudes during the second and third centuries of the church. Apologists writing in defense of the faith often insisted that Christians prove their loyalty to the government by praying for their leaders while worshiping only God.

Justin Martyr addressed his First Apology to Emperor Antoninus Pius, the Roman senate, and the people: “Therefore, we adore only God, but in other things we gladly serve you, acknowledging you as emperors and sovereigns, praying that along with your royal power you may be endowed too with sound judgment.” And Theophilus of Antioch wrote in a letter to the pagan Autolycus: “Therefore, I honor the emperor, not indeed worshiping him but praying for him.”

Even the fiery-tempered Tertullian of Carthage claimed that Christians served the emperor better than others did because “our God has appointed him [the emperor]. Since he is my emperor, I take greater care of his welfare . . . because I pray for it to one who can grant it.”

What was the attitude of early Christians toward civil servants and their own possible public service? Much of what we find in the New Testament and among the church fathers’ writings deals generally with the emperor and governing authorities. Occasionally, however, we read reports of specific encounters involving individual Christians.

The New Testament writers record several interactions with governmental representatives—Roman centurions and other soldiers; tax collectors, who collaborated with the Roman occupiers; a royal official from Herod Antipas’s court; proconsuls, including Sergius Paulus of Cyprus, who believed Paul’s and Barnabas’s preaching; imperial guards in Rome, who heard the Gospel from Paul; governors; and even kings.

Some of these encounters resulted in conversions to Christianity, but even then none were instructed to quit their jobs except Levi (Matthew), who left his tax booth to follow Jesus. Even tax collectors and soldiers who responded to John the Baptist’s call to repentance were not told to resign, but only to perform their duties honestly.

Nonetheless in early church writings, we find no evidence for Christians in the military prior to 170 or in government service until even later. In fact catechumens applying for baptism were interrogated about their service in the military or the government. In the Apostolic Tradition, an early third-century church manual, Hippolytus of Rome outlined restrictions on occupations for Christians:

A soldier who is in authority must be told not to execute men; if he should be ordered to do it, he shall not do it. He must be told not to take the military oath. If he will not agree, let him be rejected [from joining the church].

A military governor or a magistrate of a city who wears the purple, either let him desist or let him be rejected. If a catechumen or a baptized Christian wishes to become a solder, let him be cast out. For he has despised God.

Taking the sword from soldiers

During the several-years-long process of catechism to prepare for baptism, Apostolic Tradition explains that baptismal candidates agree to limitations. Soldiers and magistrates were rejected unless they resigned from their positions.

An exception was usually made for soldiers who served as police or during peacetime. Tertullian, however, made no exceptions, writing in On Idolatry: “But how will a Christian war? Indeed how will he serve even in peace without a sword, which the Lord has taken away? . . . The Lord, in disarming Peter, unbelted every soldier.”

This absence of Christians from public service provoked criticism from their detractors; such civic duty was important in Roman society. The pagan Caecilius complained to the Christian Octavius that Christians “do not understand their civic duty.” Celsus, a Greek philosopher and opponent of Christianity, insisted that Christians should “accept public office in our country”; otherwise, they were shirking their duties to society and neglecting their obligation to protect the empire while receiving its benefits.

Origen of Alexandria, responding in Against Celsus, defended his fellow Christians on the basis of their higher calling: “But they keep themselves for a more divine and necessary service in the church of God for the sake of the salvation of men. Here it is both necessary and right for them to be leaders and to be concerned about all men, both those who are with the Church . . . and those who appear to be outside it.” Tertullian agreed: “We have no pressing inducement to take part in your public meetings. Nor is there anything more entirely foreign to us than affairs of state.”

Early Christian apologists put forward many reasons for Christians not to perform military service. First the law of Christ called for Christians to “beat their swords into plows and their spears into pruning knives” (Isa. 2:4) and to love their enemies. On this Justin, Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Origen all agreed.

Second, as Tertullian noted, Christians would be forced to participate in Roman idolatry and oaths to the emperor, including emperor worship.

Third, said Origen, “The more pious a man is, the more effective he is in helping the emperors—more so than the soldiers who go out into the lines and kill all the enemy troops that they can.” Spiritual soldiers take up the full armor of God, he said, and engage in prayer on behalf of all in authority. Indeed Christians composed “a special army of piety through our intercessions to God.”

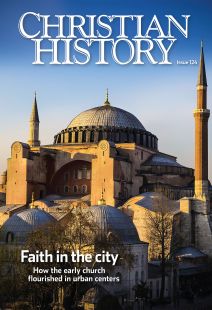

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

In reality some Christians did serve in the military. In 173 the Thundering Legion included those recruited from the strongly Christian region of Armenia. In his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius wrote that during a campaign on the frontier of the Danube, the Roman army, under the leadership of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, suffered from drought, whereas their enemies had ample supplies of water. After Christian soldiers prayed for rain, not only did rain refresh the Romans, but the accompanying thunder and lightning frightened their opponents.

Tertullian passed along this same story as part of his defense of Christianity, but he still disapproved of Christians in the military. No baptized Christian is able to enlist, he said, and anyone already in military service must abandon the army at the time of baptism: “There is no agreement between the divine and the human oath, the standard of Christ and the standard of the devil, the camp of light and the camp of darkness.” Nonetheless even his protests are evidence that Christians served in the army at the turn of the third century.

Fighting for Christ

Many of these Christian soldiers, however, suffered persecution and martyrdom. During Decius’s persecution in 250, Bishop Cyprian of Carthage related the story of two soldiers who were martyred. In 298 a centurion named Marcellus refused to worship the Roman gods, renounced his position in the army, and at his trial, testified: “It is not fitting that a Christian, who fights for Christ his Lord, should fight for the armies of this world.”

During the prelude to the great persecution of Diocletian and Galerius, the first to suffer were Christian soldiers, Eusebius said—presumably because their commitment to the empire was questioned.

One of the great stories of persecution among Christian soldiers is the Acts of the 40 Martyrs of Sebaste. The Edict of Milan had supposedly ended persecution in 314, but Emperor Licinius reneged on this agreement and attempted to purge his army of Christians. Evidently he feared their loyalty to Constantine, who had granted them toleration.

Licinius’s edict was eventually delivered to the Twelfth Legion, successors of the Thundering Legion and now stationed in Sebaste (in modern Turkey). In 320 this famed legion still included 40 committed Christians. When they refused to recant their faith, the governor conceived a torturous punishment that he hoped would break their defiance: he ordered them to strip and to stand naked upon an icy lake until they relented.

Throughout the night the Christians encouraged each other to remain faithful and to maintain the sacred number of 40. Sadly one soldier relented and left the lake to seek refuge in a heated tent on the shore.

But then a guard on the shore decided to confess his faith in Jesus Christ, to join the Christians in their suffering, and to take the place of the deserter. He stripped off his clothes and confessed, “I am a Christian!” Thus, the story relates, God answered the martyrs’ prayers that their number would be complete. By the next day, all 40 Christian soldiers had died—but each martyr had earned the crown of life.

From governor to bishop

While unknown numbers of Christians enrolled in military service before 314, few reports tell of public service among Christians. In 278 Bishop Paul of Samosata also held the post of civil magistrate, but Eusebius criticized him for his arrogance and pomp, not to mention his heretical views. Evidently public jobs were further out of reach for Christians than military service was.

This situation, of course, completely reversed with the conversion of Emperor Constantine. Upon achieving sole rule as emperor in 324, he set upon the task of Christianizing the Roman Empire. He appointed Christians to public offices and took many as his personal advisers, opening government jobs to Christians. He ordered all soldiers to worship the supreme God on Sundays. Whatever he meant by that decree or however it was interpreted by soldiers, he had legitimized the service of Christians in the army and the magistracy.

Perhaps the story that best illustrates the cooperation of church and state in the fourth-century empire is that of Ambrose, bishop of Milan. Ambrose began his public career as governor of Milan, and his ambitions were political. But in 373 the death of the Arian bishop Auxentius threatened the peace of his city, which was divided over Arianism and Nicene orthodoxy.

Ambrose decided to preside over the election of Auxentius’s successor. Surprisingly a child in the crowd began to cry out, “Ambrose, bishop!” The crowd took up the chant. Ambrose had no intention of accepting an ecclesiastical position, but Emperor Gratian insisted that his secular governor would now serve the empire best as bishop of Milan.

It is ironic that Ambrose, who was not yet a church member, was selected as the best choice for bishop. At the time he was only a catechumen, so he submitted to baptism, ordination, and consecration as bishop all in eight days!

Church and state, however, did not always harmonize. When Emperor Theodosius I commanded the slaughter of 7,000 Thessalonicans, Ambrose condemned him and demanded clear signs of his repentance.

The next time the emperor appeared at the church in Milan, the bishop met him at the door and refused him entrance: “Stand back! A man such as you, defiled by sin, with hands covered by the blood of injustice, is unworthy, without repentance, to enter this sacred place, and to partake of holy communion.” Theodosius made his contrition publicly; in this case, the state yielded to the church.

In 380 that same emperor completed the interlocking of church and state by declaring orthodox Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. Two generations later his grandson, Theodosius II, instituted a law that permitted only Christians to serve in the military, thereby expecting divine favor to rest upon the imperial armies.

The distinction between “the things that are Caesar’s” and “the things that are God’s” established by Jesus and the apostles had had now become less clear. Today we still look back to the complicated legacy of the early church as we try to obey God and Caesar, to live as citizens of heaven while residing in the world. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #124 Faith in the City. Read it in context here!

By Rex D. Butler

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #124 in 2017]

Rex D. Butler is professor of church history and patristics at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and the author of The New Prophecy and “New Visions”: Evidence of Montanism in the Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas.Next articles

“The same kind of Christians we have always been”

We spoke to Karen Swallow Prior, author of Booked (2012) and Fierce Convictions (2014) and professor of English at Liberty University, about how Christians ought to live as citizens in the culture.

Karen Swallow Prior and the editors“God has given us the earth as a gift”

We spoke to Jill Sornson Kurtz, a professional architect with a particular interest in designing sustainable buildings for everyday life, on her work as a Christian in the building industry today.

Jill Sornson Kurtz and the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate