Christianity goes to town

TODAY YOU DON'T NEED TO TRAVEL to Rome to view classic Roman architecture: its stately columns, arches, and domes have been copied worldwide. The originals invoked stability and continuity in Rome’s diverse empire, embracing all of the world that Rome thought mattered.

Marble temples and basilicas provided visible stability and continuity for religious cults and imperial institutions. And the emperor himself, or at least his image, oversaw business agreements and legal deals. His likeness had the same legal and religious force as the man in the flesh; sacrifice was to be offered to the emperor, and his image, as divine.

Of course Christians had a problem with this, and thus the empire had problems with them. What began as mere rooting out of troublesome “anarchists” resulted in a conflict between the claims of a universal state and the claims of a universal religion. Over the course of his reign, Constantine managed to align these previously conflicting interests.

Christians are everywhere

Tertullian (c. 155–c. 240) proclaimed that Christians filled “cities, villages, markets, the camp itself, town councils, the palace, the senate, the forum. All we have left you is your temples. . . . Nearly all the citizens of all your cities are Christians.”

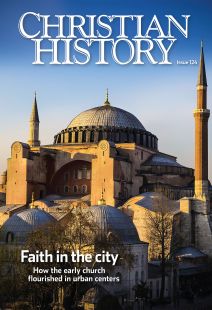

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Tertullian’s enthusiasm may have run away with him, but it is true that by his time Christians were numerous, if still a minority. During the Decian Persecution (249–51), a church flourished at Dura Europos, an important garrison town on the edge of the empire. Converted from a house (probably around 232), it was much less visible than pagan temples and even the synagogue, but its existence must have been public knowledge.

The Christian presence in Dura Europos seems to have had little effect on the townscape. But things were different in Rome, particularly by the time of Constantine. His gift of the imperial Palace of the Lateran in Rome, his building of imperial basilicas, and the grant of imperial honors to the bishop of Rome helped make the empire’s capital a stage for the symbolic confrontation between Christianity and paganism. The senate building and the ancient temples of the old religion still occupied the heart of the city, encircled by parish churches (tituli) and basilicas in the residential areas.

At the end of the fourth century, the apse of Santa Pudenziana in Rome was given a mosaic showing Christ enthroned on what appears to be the rock of Golgotha—pictured in the courtyard of the Great Church of Constantine in Jerusalem, where the Church of the Holy Sepulchre now stands. The city was now a figure of the City of God.

Traveling liturgies

In the primitive church, all Christians gathered with their bishop on Sundays and feast days to celebrate the liturgy. As membership grew sheer force of numbers made it impossible for all to gather in one place as a single congregation.

From the pilgrim Egeria in the late fourth century, we have a description of Jerusalem over the course of the liturgical year. Worshipers used prayers and readings appropriate to the day in places associated with biblical events, often with processions between sites. Jerusalem had only recently been rebuilt with magnificent imperial basilicas, and the traveling liturgies folded all the sites into a sumptuous liturgical cycle of prayer and praise and thanksgiving .

By the fifth century, we see the church in Rome doing this too: calling it the “stational” liturgy, the pope processed with a military guard and banners to different churches on appropriate days (such as Santa Maria Maggiore, where the relic of Jesus’ manger was kept, on Christmas). With each visit consecrated bread from the previous Eucharist was included with the new bread; at the end of the service, new bread from the service was distributed and some reserved for the next celebration.

In 330 Constantine chose Byzantium as the empire’s new capital and renamed it Constantinople after himself. Much has been made of Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, but the unfolding of that conversion is complicated. Constantine staged public displays of Christianity and was adept at self-promotion. He had been a devotee of the sun god Sol Invictus, the Invincible Sun. On top of a huge column in what was then the Forum of Constantine, he placed a statue of Apollo, the Roman sun god, adapted with his own features and including rays around his head made of nails reputedly used in the crucifixion of Christ.

Constantine dedicated his city with 40 days of ceremony culminating with the first games staged in his new hippodrome, filled with thousands of people. The games ended with a wooden statue of the emperor bearing the tyche, or spirit of the city, being borne around the track to halt before Constantine in his royal box. This was to be repeated annually: “The reigning emperor should arise and pay homage to the statue of the emperor Constantine and the Tyche of the City.” (To see a tyche, check out p. 35.)

Constantine is said to have included a variety of relics in the base of the column: the palladium (the statue of Athena that Aeneas had carried from Troy to Rome), the ax with which Noah built the ark, the basket from the miraculous feeding of the 5,000, and Moses’s stone from which water sprang during the Exodus. All this imagery is a curious mix of Christian and pagan.

The thirteenth apostle

Bishop Eusebius (c. 263–c. 339), a friend and counselor of the emperor, was willing to overlook the pagan elements of Constantine’s civic pride. This pioneering church historian described the city and its architecture as Christianized:

Honoring with special favor the city which is called after his own name, [Constantine] adorned it with many places of worship and martyrs’ shrines of great size and beauty. . . . He determined to cleanse of all idolatry the city which he declared should bear his own name; so that there should nowhere appear in it statues of the supposed gods worshiped in temples, nor altars defiled by pollutions of blood, nor sacrifices burnt by fire, nor demonic festivals, nor anything else that is customary among the superstitious.

There is no doubt that Constantine had brought sculptures from despoiled pagan shrines throughout the empire, and Eusebius must have known this. Perhaps his point was that Christianity visibly eclipsed their previous fame as cult images as Constantine collected them together. This is read differently now by different people and doubtless was then too. This type of ambiguity was necessary for Constantine; he needed the political allegiance of the still overwhelmingly pagan Roman senate as well as the more Christian one in Constantinople.

On Constantine’s death in 337, the Roman senate requested that his body be sent to Rome, presumably for traditional pagan ceremonies, but the senate of “New Rome” refused. Constantine was laid to rest at the Apostoleion, a church built to house relics of the apostles—symbolically elevating him in death to the status of the “thirteenth apostle.” Eusebius described the ceremony in language familiar to the Roman senate, but in a later text he calls Constantine “Savior” and “Good Shepherd,” identifying the emperor of this world with the emperor of heaven.

Church and city would continue to intertwine at Constantinople, with imagery of empire used alongside that of heaven on earth. The tenth-century Book of Ceremonies describes how both characterized the coronation ceremony for Leo I in 457.

It began on the Hebdomon, a military parade ground outside the walls of the city near the sea where the commanders placed a circlet on Leo’s head; the army, then the people, acclaimed him as “a new David, a new Constantine.” The clergy returned to Hagia Sophia to await his arrival. The new emperor made his way via two shrines to John the Baptist where he dedicated his diadem on the altars.

Then Leo entered into the city via the Golden Gate where the keeper of the palace met him. Clothed in purple and taken by chariot to the Forum of Constantine, he was greeted by the Prefect of the city before processing to the open space between the Great Palace and the Great Church. There he greeted the patriarch of Constantinople and processed to the sanctuary with him: the two halves of the rule of Christ on earth.

Pale yellow and swirling red

Justinian assumed the throne in 527, his own coronation ceremony much abbreviated, as he had been acting as regent for his dying uncle. In 532, during the Nika Riots, fire destroyed most of Constantinople, including much of the Great Palace and Hagia Sophia. Very nearly toppled from the throne, to reassert power Justinian rebuilt a far greater city, palace, and church with astonishing speed.

Less than six years later, the awe-inspiring new Hagia Sophia was consecrated. The whole of the empire had yielded up its riches, “forty thousand pounds’ weight of silver” embellishing the sanctuary alone. In early 563 Paul the Silentiary wrote a poetic description of Hagia Sophia:

You may see the bright green stone of Laconia and the glittering marble with wavy veins found in the deep gullies of the Iasian peaks . . . the pale yellow with swirling red from the Lydian headland; the glittering crocuslike golden stone which the Libyan sun, warming it with its golden light, has produced on the steep flanks of the Moorish hills; that of glittering black upon which the Celtic crags, deep in ice, have poured here and there an abundance of milk. . . . Such works as these our bountiful Emperor built for God the King.

Only the emperor himself had the power to command these far-flung resources on such a vast scale: the geography and geology of empire was literally built into the fabric of the church.

Emperors including Justinian made ceremonial processions across the Great Palace and into Hagia Sophia on high feast days. These began in the throne room where the emperor was presented with the relic of Moses’ rod, still in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul today: the emperor was assuming the role of a new Moses, the empire was the new Promised Land, and the city the New Jerusalem.

Procopius, Justinian’s chronicler, described in considerable detail the way Justinian built and renovated palaces, harbors, cisterns, baths, and visitors’ accommodations. He even recorded the emperor’s suppression of brothels and provision for former prostitutes to enter the cloister.

This demonstrated the impact of Christianity on the development of the city, but perhaps the most important thing was how, by the time of Procopius, the theology of empire had become thoroughly modeled in the fabric of the city. No less than the entryway into Hagia Sophia (see p. 30) claims the peace and unity of the empire, the church, and the city. But beware of easy assumptions—sometimes strong imagery is necessary to shore up weak realities. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #124 Faith in the City. Read it in context here!

By Allan Doig

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #124 in 2017]

Allan Doig is fellow, chaplain, and tutor for graduates at Lady Margaret Hall and a member of the faculty of theology in the University of Oxford. He is the author of Liturgy and Architecture: From the Early Church to the Middle Ages and the forthcoming The History of the Church through Its Buildings.Next articles

“God has given us the earth as a gift”

We spoke to Jill Sornson Kurtz, a professional architect with a particular interest in designing sustainable buildings for everyday life, on her work as a Christian in the building industry today.

Jill Sornson Kurtz and the editors“The transformative love of God in our lives”

Greg Forster is director of the Oikonomia Network at the Center for Transformational Churches, Trinity International University. These reflections on Christians and culture are adapted from a blog series at The Green Room.

Greg ForsterFaith in the city: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you understand the early church as an urban movement.

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate