“Our garden must be God’s garden”

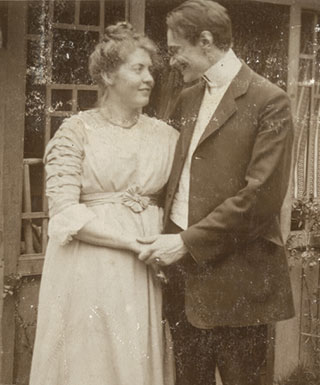

IN JUNE OF 1920, Eberhard Arnold (1883–1935); his wife, Emmy (1884–1980) [the pair shown at the left]; and their five children moved from Berlin to the German village of Sannerz. Their new temporary home: a shed behind the village inn. Their goal: to put into practice the teachings of Jesus in the spirit of the first Christians in the book of Acts. Their vision: a community of goods and work, with an open door, as an embassy of God’s coming kingdom.

The way of peace

What compelled the Arnolds to leave their comfortable home, and Eberhard’s budding career as a publisher and a speaker, for this path of radical community? In the aftermath of World War I (1914–1918), Germany was devastated and her masses impoverished. Eberhard saw the war as God’s judgment on a false Christianity corrupted by greed and power; he believed the established church had betrayed Jesus’ way of peace.

The Arnolds wanted to do something to address the dire social conditions in the city. They debated whether they should stay or establish a healthier life away from the cities and invite others to join them there. With food still in short supply, even their own children were suffering from poor nutrition.

The scales soon tipped in favor of the move to the country. Before the war began, growing circles of young people, the Youth Movement, had begun to search for a new kind of life. Inspired by itinerant tramps called Wandervögel, or “birds of passage,” young men in shorts and loose tunics and young women in simple, bright dresses hiked out into nature armed with violins and guitars in search of a more natural, genuine life.

Order Christian History #119: The Wonder of Creation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

These young people thought urban middle-class life held only class consciousness, cramped social relationships, and fleeting fashions; they were fed up with big cities, oppressive factories, stuffy etiquette, and dry, formal education. Social position, wealth, modern comforts, and religiosity no longer counted for anything.

This movement resonated deeply with Eberhard and Emmy Arnold. Could they establish a life that was genuine and free in the cities? Could God’s kingdom come afresh on earth amid the decadence and squalor of urban life?

No, they decided; Christianity must be reborn in the pure air of nature. It must be rooted again in the fields of God’s good earth, with fresh, earthy smell on feet and hands. They responded to the challenge of German social anarchist Gustav Landauer (1870–1919): “Land and spirit must meet; culture of the spirit has to be combined with work on the land.”

From the outset as many as 2,000 guests a year flooded the community the Arnolds founded in Sannerz. Fortunately they soon rented a large villa across the road from their initial shed. It came with farm equipment and livestock: cows, goats, pigs, and chickens.

The community grew slowly but steadily. People joined from all walks of life; there was plenty of work and youthful enthusiasm even if experience was lacking. Living on a shoestring, the community supported itself through publishing and donations while gradually developing its farm and garden. It also took in foster children. Physical labor was considered essential to the communal experience.

“We believe in a Christianity that does something,” Eberhard Arnold wrote. “Daily work with others is the best and quickest way to find out whether we are willing to live in community on the basis of real love and faith.”

But work did not preclude lively discussions in the evenings, or hikes in the open country. Gathering around a bonfire or under the trees to sing folk songs, dance, or tell legends brought together community members, visitors, and neighbors—who would often, given the early community’s poverty, bring along something for everyone to eat.

“We love the soil”

The established group grew to 50 people by 1927, necessitating a move to a large farmstead, the Sparhof, seven miles away. It was an isolated spot with rocky soil and sharp north winds. The buildings were dilapidated and the fields neglected. The community took up the challenge. They combined three farms, built houses, and set up workshops. The settlement became known as the Bruderhof, after Anabaptist communes of that name in the sixteenth century.

Everyone had to be involved in agricultural work, regardless of their experience, education, or gifts. The group had no money to buy food and struggled to grow enough. But Eberhard Arnold also believed in the spiritual significance of cultivating the land:

We love the body because it is a consecrated dwelling place of the spirit. We love the soil because God’s spirit spoke and created the earth and because he called it out of its uncultivated natural states so that it might be cultivated by the communal work of man. We love physical work—the work of muscle and hand—and we love the craftsman’s art, in which the spirit guides the hand. In the way spirit and hand work through each other we see the mystery of community.

Because the soil at the Sparhof had been neglected for so long, farming never really provided the community’s livelihood. The community decided to plant windbreaking trees on the hill behind the houses. Hundreds of spruce and larch saplings were set out, along with cherry, plum, and apple trees.

This helped, but everything was still in short supply. Garden vegetables ripened late because of the high altitude, and potatoes only lasted to the end of spring. Although they could grow their own wheat, it was not enough to see them through to the next harvest. At times, they ate meal after meal of wild meadow spinach.

Whenever possible the community, children, and guests worshiped outdoors to experience God in nature. Prayer, study, and worship were not to be at odds with farming. Neither was the intellectual work of the publishing house. Sometimes members read and discussed manuscripts while sorting potatoes or taking turns stirring the large jam kettle.

Simplicity did not mean abandoning technology. “Nothing of the mechanical and technical achievements of the last centuries should be lost!” Eberhard Arnold wrote. “But the degrading and brutalizing of the working class clings like a blight, a curse, to the tools, factories, machines, and industry of today.” For him modern factories in which people performed soulless labor with no community of heart were contrary to God’s order. By contrast, he thought that in a community based on faith and love technical innovation could protect and serve the dignity of each person and the needs of the common life.

Work for the kingdom

With the rise of Hitler, the Bruderhof, with its commitment to nonviolence, was forcibly expelled from Germany. They went to England and then Paraguay, and the community found itself closer to nature than it might have wished, again and again struggling to eke out a living in primitive conditions. Several hundred found their way to the United States in 1954. Eberhard had died in 1935, but Emmy followed the community’s way of life until her death in New York in 1980.

There are now close to 25 Bruderhof communities on five continents: many rural, some urban. While most support themselves through light industry, the original impulse to live close to the land remains. They try to grow most of their own food, to use sustainable farming techniques and alternative energy, to make conservation efforts on their lands, and to use natural materials in the furniture and toys they produce.

As well, communities practice simplicity of dress and a wholesome diet, emphasize outdoor play and exploring nature in children’s education, and frequently meet while turning compost, chopping firewood, and sapping maple trees. Even communities in city neighborhoods have small gardens. In all these things, traces of Eberhard Arnold’s original vision remain:

Whatever our work, we must recognize and do the will of God in it. God . . . formed nature, and he has entrusted the land to us, his sons and daughters, as an inheritance but also as a task: our garden must become his garden, and our work must further his kingdom. CH

By Charles E. Moore

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #119 in 2016]

Charles E. Moore is a member of the Bruderhof community; teaches at the Mount Academy in Esopus, New York; and writes for Plough Quarterly. His two most recent books are Bearing Witness: Stories of Martyrdom and Costly Discipleship and Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for His People.Next articles

A cathedral, a retreat, a challenge

American Methodists worshiped in God’s creation even as they looked to the world beyond

Russell E. RicheyHeaven under our Feet

What did the son of a pencil-maker have in common with the Transcendentalists?

Jennifer Woodruff TaitCosmic worship, sanctified matter, transfigured vision

Christian poets, mystics, priests, and preachers encourage us to worship God by experiencing his creation

Kathleen A. MulhernSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate