Reading the “book of nature”

WHEN CHARLES DARWIN left England to circumnavigate the world in 1831, he didn’t come across a single scientist. The word “scientist” was not coined until two years later; so many people were doing scientific work in so many different fields that the need arose for a single word by which to refer to all of them collectively.

When scientists talk God

Prior to that time, the closest equivalent to “scientist” was “philosopher,” and the general enterprise of studying nature was often called “natural philosophy.” It’s no accident that the first scientific society in North America, founded in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin in 1743, is called the American Philosophical Society. That older language conveys a crucial fact: in earlier centuries, science was more openly tied to philosophical, even to theological, ideas, and scientists were more willing to speak about God.

In fact many of the scientists who created modern science during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—a period often called the “Scientific Revolution”—were serious Christians who did not hide their faith in the privacy of home and church. Their ideas about God and creation influenced how they viewed their scientific work; they launched a new desire to learn more about God through studying the “book of nature” (his creation), as well as through the “book of Scripture.”

Although the Scientific Revolution happened in Christian Europe and most of the people involved were Christians, that’s not when science itself began. Natural philosophy, including extraordinarily sophisticated work in astronomy, occurred in places like Athens and Alexandria centuries before the birth of Jesus. Christian authors before around the sixth century responded to Greek science mostly by incorporating a limited set of those ideas into their theological writings, not by making original contributions of their own.

That all began to change when John Philoponus (490–570) wrote insightful commentaries on certain works of Aristotle (384–322 BC). But a critical mass of Christian scientists did not exist until about the twelfth century, when universities sprang up across western and southern Europe, and Aristotle’s works took center stage in the curriculum.

Order Christian History #119: The Wonder of Creation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

This natural philosophy changed fundamentally during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when ideas based on Aristotle gradually gave way to ideas now associated with modern science. Christian beliefs strongly influenced three prominent features of this Scientific Revolution: a new view of nature, a new view of how to investigate nature, and a new way to praise God.

A new view of nature

Before the Scientific Revolution, “Nature” was often personified—as a wise, almost divine, being that actively supervised natural phenomena and formed a central part of scientific explanations. The legacy of Aristotle and of Greco-Roman physician Galen (129–c. 216) gave rise to expressions such as “Nature abhors a vacuum” and “Nature does nothing in vain.”

Proponents of the new science decisively rejected that way of thinking. Instead they reconceived natural objects as impersonal machines incapable of acting purposefully on their own. (Later thinkers would react against this idea and seek a re-enchantment of nature: see “Rooted on Kentucky’s land,” p. 9, and “Heaven under our feet,” p. 33.) But these scientists also affirmed that the Creator had acted purposefully in creating nature with certain specific properties.

It became a goal of science to explain nature by analogy with human technology, especially clocks. Astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) said, “My aim is to show that the heavenly machine is not a kind of divine, live being, but a kind of clockwork.”

No one agreed more with Kepler than chemist Robert Boyle (1627–1691). In his opinion the older notion of an intelligent “Nature” is “injurious to the glory of God, and a great impediment to the solid and useful discovery of his works”—since it shuts down further inquiry into the actual workings of the universe and makes human efforts to do so seem irreverent.

Instead, with great enthusiasm, Boyle promoted what he called the “mechanical philosophy” as both scientifically and theologically superior. In his opinion, since the universe is like a “great Automaton” or “a rare Clock,” it cries out for a Creator and clockmaker, none other than “the Divine and Great Demiourgos [craftsman], as both Philosophers [Plato] and sacred Writers [Hebrews 11:10] have styl’d the World’s Creator.” It is indeed no accident that the rise of the mechanical philosophy overlapped with the high-water mark of natural theology, the attempt to understand God’s nature and design through observation and experiment. Boyle stood at the meeting of both.

Simultaneously with this new view of nature came, secondly, a new view of how to gain knowledge. In universities prior to the Scientific Revolution, knowledge in all fields was gleaned from reading ancient books and later commentaries on them. Modern universities still use similar methods in biblical studies, law, and some other disciplines in the humanities.

Originally such analysis and interpretation of texts was also the basis for earning advanced degrees in medicine and natural philosophy. This changed during the Scientific Revolution: commentary on ancient texts was out, and experiments were in. The divinely authored “book of nature,” accessed by observations and experiments, came to be seen as more authoritative than any merely human book, regardless of its author.

Thus the great anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) set aside the long-revered books of Galen, replacing them with “this true book of ours—the human body—man himself.” William Harvey, who discovered the circulation of the blood through careful experimentation, considered it “base,” or lowly, to “receive instructions from others’ [books] without examination of the objects themselves, as the book of Nature lies so open and is so easy of consultation.” Philosopher and statesman Francis Bacon (1561–1626) likewise urged readers never to think they could “be too well studied in the book of God’s word [Scripture], or in the book of God’s works [nature]”; they should strive for “an endless progress or [proficiency] in both.”

Reason and experience combined

This new emphasis on observing and testing nature by hands-on experience contrasted with an alternative approach that also played an enormous role in the Scientific Revolution: the application of mathematics and pure reason. Scientific knowledge today is universally understood as emerging from both reason and experience, but few modern scientists realize that theological debates about God’s reason and God’s will were instrumental in getting here.

The debate asked which was more important in understanding God’s relationship to the created order—God’s reason, which humans share to some degree as creatures made in God’s image, or God’s will, not completely bound by the dictates of human reason? Those who stressed divine reason also stressed the transparency of nature to human reason. Those who stressed divine freedom emphasized the limits of reason in plumbing the depths of creation.

Leading scientists and philosophers lined up on both sides. Kepler and astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) believed that since a divine mathematician had created nature, we can attain fully reliable scientific knowledge through the mathematical symbols in which the book of nature

is written.

On the other hand, Boyle and physicist Isaac Newton (1642–1727) believed that the Creator is not subject to human ideas of how things ought to be done—so we must start with nature, not our own minds, to learn what God actually did.

Either way, proponents of the new science provided solid theological reasons for reading the book of nature in certain ways. They also found God’s wisdom, goodness, and power prominently displayed in the pages of that book and believed that drawing theological conclusions was part and parcel of doing natural philosophy.

Newton said that “the main Business of natural Philosophy” was to show the existence of God; he thought the best evidence for this came from the regularity and stability of the solar system and the wonderful bilateral symmetry of the bodies of animals. Perhaps more than anyone else, Boyle and Kepler made the practice of science a religious activity in itself: they saw themselves as priests in the temple of nature with, finally, a new way to give praise to the Creator they found there. Kepler said in a letter to a Catholic astronomer and statesman that since “we astronomers are priests of the highest God in regard to the book of nature, we are bound to think of the praise of God and not of the glory of our own capacities.” Boyle likewise wrote, “If the World be a Temple, Man sure must be the Priest, ordain’d (by being qualifi’d) to celebrate Divine Service not only in it, but for it.”

Since God’s world is full of “inanimate and irrational Creatures” that cannot comprehend their Creator and acknowledge their debt to him, it is humans who must praise God on their behalf: “Man, as born the Priest of Nature, and as the most oblig’d and most capable member of it, is bound to return Thanks and Praises to his Maker, not only for himself, but for the whole Creation.”

The Bible in the lab?

Clearly Christianity influenced conceptions of what scientific knowledge is, how we obtain it, and what to do with it—and biblical notions of God, humanity, and creation were not too far below the surface in that conversation. But, surprisingly, many early modern scientists did not apply the book of Scripture directly to their explorations into the book of nature.

These scientists studied the Bible intensely and some of them wrote lengthy treatises about it, but as a rule, they did not bring the Bible into the laboratory or the observatory, usually because they didn’t see its relevance to the immediate matters at hand.

No one revered the Bible more than Boyle, who learned the biblical languages on his own initiative and wrote one million words on biblical and theological subjects—including a book defending the inspiration of Scripture against literary critics.

But in 1664 and 1665, he published two large books of experimental observations, one about light and the colors of objects and the other about the effects of very cold temperatures—around a quarter million words altogether. The word “God” appears just eight times, all but once as part of thankful or hopeful expressions, such as “God permitting” or equivalent utterances that add nothing to the scientific content, even while they add much to our understanding of Boyle.

Boyle believed profoundly that God had created the natural world, but he didn’t use God or biblical texts in the lab to help him understand his observations or design his next experiment. Likewise the first edition of Isaac Newton’s greatest book, The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687), mentions God only once. The second edition includes a short essay about God and nature with numerous references to the Bible, but it leaves the “mathematical principles” themselves unchanged—Newton was simply telling his readers what the science meant, not how to do it.

Some even thought that the Bible could actually stand in the way of scientific progress if it wasn’t interpreted with sufficient subtlety. The most famous instance involved Nicolaus Copernicus’s theory that the earth orbits the sun, rather than vice versa. Sometimes the Bible seems to deny the Copernican view in very clear language: according to Psalm 93, “the world also is established, that it cannot be moved.” Psalm 104 blesses the Lord, “who laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not be removed for ever”; and, as Martin Luther pointed out, “Joshua commanded the sun to stand still and not the earth” in Joshua 10.

But it does move

Today we almost instinctively read those Scriptures differently, but virtually all sixteenth-century readers believed that the Bible taught the immobility of the earth. A sea change in interpretation took place when Christian astronomers cautioned the clergy to keep the Bible out of astronomy. Galileo declared (in words he borrowed from a Catholic cardinal), “The intention of the Holy Ghost is to teach us how one goes to heaven, not how heaven goes.” This attitude came to be widely adopted by the end of the seventeenth century and is commonplace among Christian scientists today.

Scientists of this era emphasized the need for God to communicate with unlearned audiences in popular language not well suited for scientific accuracy. Kepler, the greatest astronomer of his age and a former Lutheran divinity student, said: “Now the holy Scriptures, too, when treating common things (concerning which it is not their purpose to instruct humanity), speak with humans in the human manner, in order to be understood by them. They make use of what is generally acknowledged, in order to weave in other things more lofty and divine.”

But none of this means that Christianity and science were engaged in ongoing, inevitable conflict during the rise of modern science. Quite the contrary—Christian theological views shaped modern science in very important ways, while science influenced how Christians read the Bible. These scientists left us a legacy of trust; trust that the God we find revealed in the book of Scripture can also be seen in the book of nature and that God’s word and God’s works both lead us to a greater love of God. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #119 The Wonder of Creation. Read it in context here!

By Edward B. Davis

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #119 in 2016]

Edward B. Davis is professor of the history of science at Messiah College and editor (with Michael Hunter) of The Works of Robert Boyle. He writes articles about the history of Christianity and science and blogs regularly for BioLogos.Next articles

A cathedral, a retreat, a challenge

American Methodists worshiped in God’s creation even as they looked to the world beyond

Russell E. RicheyHeaven under our Feet

What did the son of a pencil-maker have in common with the Transcendentalists?

Jennifer Woodruff TaitCosmic worship, sanctified matter, transfigured vision

Christian poets, mystics, priests, and preachers encourage us to worship God by experiencing his creation

Kathleen A. MulhernThe heavens declare the glory of God

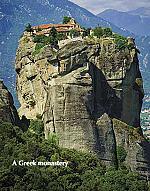

Monks and nuns left us a legacy of spirituality honoring God’s creation

Glenn E. MyersSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate