A cathedral, a retreat, a challenge

All glory to God in the sky,

And peace upon earth be restored!

O Jesus, exalted on high,

Appear our omnipotent Lord!

Who, meanly in Bethlehem born,

Didst stoop to redeem a lost race,

Once more to thy creatures return,

And reign in thy kingdom of grace.

When thou in our flesh didst appear,

All nature acknowledged thy birth;

Arose the acceptable year,

And heaven was opened on earth:

Receiving its Lord from above,

The world was united to bless

The giver of concord and love,

The Prince and the author of peace.

O wouldst thou again be made known!

Again in thy Spirit descend,

And set up in each of thine own

A kingdom that never shall end.

Thou only art able to bless,

And make the glad nations obey,

And bid the dire enmity cease,

And bow the whole world to thy sway.

American Methodists sang Charles Wesley’s words about Christ’s birth from the Pocket Hymn-Book, Designed as a Constant Companion for the Pious, pulled from pocket or purse. Counseled by fervid preaching, hymn-filled class meetings, and crowded quarterly conferences, American Methodists not only lived in, but also saw through and beyond, nature, world, and nation. The little hymnbook sings out with the wonder of the created world (the terms in bold above), but within the expressions of awe for the world that is, we find a deep longing for the world to come.

The Pocket Hymn-Book references “nature” 28 times, pointing to the world to come as often as it does to this world. “Creation” appears in seven hymns; sometimes referring to the whole world, sometimes to individual redeemed humans. “World,” less ambiguously, nearly always points to this planet (37 times). One hymn claims, “Strangers and pilgrims here below, / This earth we know is not our place” and continues, “Patient th’ appointed race to run, / This weary world we cast behind.”

“Earth” references this world over 80 times but also claims the world to come as home: “Come, let us anew Our journey pursue… , And press to our permanent place in the skies; Of heavenly birth / Tho’ wand’ring on earth, This is not our place.” Characteristically, although this particular hymn exalts in God’s created world, the last verse makes clear what it all points toward: “Gloriously hurry our souls to the skies.”

Seeing the forest and the trees

Christian hymns have always focused three ways: back to creation and to the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, upward to the Trinity, and forward to the coming of Christ. In nineteenth-century America, while other groups dwelled on centuries of verse about the glories of God’s creation, Methodists, Baptists, and other revivalistic movements focused on the forward: living into their hymnody as it pointed them toward the heavenly promised land.

John Wesley had a broader view; he described the goodness of God’s created works in his A Survey of the Wisdom of God in the Creation: or A Compendium of Natural Philosophy. But pocket hymnbooks focusing on heaven, not Wesley’s summary of Enlightenment-era science (see “Reading the ‘book of nature,’” pp. 25–29), guided the preachers he sent to assume leadership of his movement in the New World.

Yet the huge irony is this: as much as their worship focused toward a heavenly creation, Methodists worshiped in an earthly one. Specifically, they worshiped in forests. In fact, they eventually sought them out.

American Methodists tried initially to honor Wesley’s commandment to preach in fields. But his preachers discovered that his imperative had to be adjusted given the blistering American summer sun. Only a fool would endure shadeless preaching in a field and expect willing listeners to follow suit.

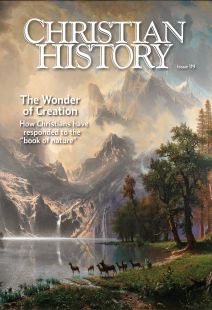

Order Christian History #119: The Wonder of Creation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Instead, when crowds exceeded the capacity of a home or small chapel, the preacher gathered the congregation cathedraled in a stately forest or under an oak’s embracing branches. (Even in notoriously cloudy Britain, Wesley reported preaching under trees or in groves about 40 times.)

American preachers also soon found these natural forest cathedrals a place for solitude, prayer, and devotions. And as they took Methodism into sparsely settled areas, particularly the western frontier, they found forests to be wild and full of dangers, some life-threatening. Sometimes Methodists brought the danger with them, as is the case in several of Methodism’s nineteenth-century divisions. Woodland meetings provided the isolation needed for dissenting Methodists to strategize and protest the church’s policy and practice on matters of race, gender, class, and style.

“All my soul was centered in God”

All three experiences of the American woodland— shady preaching spot, woods for prayer, dark challenge to itinerant preachers—defined early American Methodism and shaped the itinerancy of its first great leader, Francis Asbury (see CH 114).

In July 1776, traveling in present-day West Virginia, Asbury wrote of the forest as confessional:

“Wednesday, 31. Spent some time in the woods alone with God, and found it a peculiar time of love and joy. O delightful employment! All my soul was centered in God!”

June 1781 (also in West Virginia) brought a wilderness challenge but also woodland solitude with God:

Tuesday, 5. Had a rough ride over hills and dales to Guests. Here brother Pigman met me, and gave an agreeable account of the work on the south branch of Potomac. I am kept in peace; and greatly pleased I am to get into the woods, where, although alone, I have blessed company, and sometimes think, Who so happy as myself?

In New Jersey in June 1787, Asbury recorded one of many instances of cathedral-like preaching in

the woods:

Sunday, 24. I preached in the woods to nearly a thousand people. I was much oppressed by a cold, and felt very heavy in body and soul. Like Jonah, I went and sat down alone. I had some gracious feelings in the sacrament—others also felt the quickening power of God … I felt my body quite weary in, but my spirit not of, the work of God.

That very year the Methodists Americanized Wesley’s directive about outdoor evangelism in their book of church law, the Discipline, noting the wilderness that had already been claimed for God:

“What may we reasonably believe to be God’s Design, in raising up the Preachers called Methodists? Answ[er]. To reform the Continent, and spread Scripture Holiness over these Lands. As a Proof hereof, we have seen in the Course of fifteen Years a great and glorious Work of God, from New York through the Jersies [New Jersey], Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, even to Georgia.”

Woodland prayer and shaded preaching would conquer wildernesses, redeem citizenry, and reshape a continent. All these woodland experiences eventually came together in the dramas known as camp meetings—revivals that became a Methodist signature. It’s no wonder they appealed to Methodists and became a programmatic feature of outreach. For 30 years previous, Methodists had already gathered large crowds outdoors and under the trees for their quarterly conferences and meetings.

As years passed and the camp meeting tradition lost its grip on the entire church, late nineteenth-century Methodism reimagined and reinvented its wildernesses. On the one hand, the Chautauqua movement made woodland cathedrals a site for extensive, national Sunday school training and programming. On the other hand, Holiness movement advocates transformed camping into a nationally orchestrated and carefully planned campaign for denominational renewal, through a fresh commitment to holiness of heart and life (see CH 82 and 114).

Methodists found the world around them hard to avoid, whether as natural cathedral, devotional retreat, or wilderness challenge. Heaven might lie ahead, true; but as Charles Wesley wrote, “God had also, through Christ’s incarnation, opened heaven for them on earth and began his peaceable reign.” CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #119 The Wonder of Creation. Read it in context here!

By Russell E. Richey

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #119 in 2016]

Russell E. Richey is research fellow of the Center for Studies in the Wesleyan Tradition, dean emeritus of Candler School of Theology, William R. Cannon Distinguished Professor of Church History Emeritus at Emory University, and the author of Methodism in the American Forest.Next articles

Heaven under our Feet

What did the son of a pencil-maker have in common with the Transcendentalists?

Jennifer Woodruff TaitCosmic worship, sanctified matter, transfigured vision

Christian poets, mystics, priests, and preachers encourage us to worship God by experiencing his creation

Kathleen A. MulhernThe heavens declare the glory of God

Monks and nuns left us a legacy of spirituality honoring God’s creation

Glenn E. MyersSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate