Natural adversaries

Has Christianity always warred with science? Or, conversely, did Christianity create it? In issue #76, CH asked these questions of David Lindberg (1935–2015), Hilldale Professor Emeritus of the History of Science at the University of Wisconsin. Here is an excerpt.

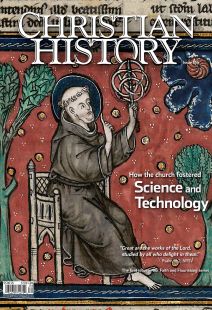

[Burning Almaricians—Chronicles of Saint-Denis. 15C. Attributed to Jean Foucquet. National Library of France]

Christian History: Many people today have a sense that the church has always tried to quash science. Is this, indeed, the case?

David Lindberg: This view, known as the “warfare thesis,” originated in the seventeenth century, but came into its own with certain radical thinkers of the French Enlightenment. These people were eager to condemn the Catholic Church and went on the attack against it.

CH: What other myths about science and Christianity are commonly accepted today?

DL: One obvious one is that before Columbus, Europeans believed nearly unanimously in a flat earth. . . . The truth is that it’s almost impossible to find an educated person after Aristotle (d. 322 BC) who doubts that the earth is a sphere. In the Middle Ages, you couldn’t emerge from any kind of education, cathedral school or university, without being perfectly clear about the earth’s sphericity and even its approximate circumference.

CH: Was there medieval conflict between them?

DL: Christianity and science had a complex relationship. Before Christ’s birth, Aristotle and Plato had written treatises on scientific questions; centuries later, Ptolemy and Galen would do so. These books entered medieval Christendom during the twelfth century in Latin translation from Greek and Arabic versions. Christian scholars immediately realized that these books were impressive and valuable, teaching them how to think about a wide range of scientific questions. But it was also clear that [they] contained theological landmines. . . . Medieval scholars had a terrible dilemma. They were not prepared to compromise the central doctrines of Christian theology. But they also recognized that the classical sciences had great explanatory power. . . . They corrected the ancient sources where that seemed necessary, and on occasion they reinterpreted theological doctrines. And they argued vigorously for the usefulness of the classical sciences.

There were certainly skirmishes, including several cases in which a university scholar was condemned for teaching doctrines judged dangerous, but most were local and temporary. And there was never anything approaching intellectual warfare. . . . In the end Christendom made its peace with the classical tradition. Aristotle’s writings became the centerpiece of medieval university education, and the church became their greatest patron.

CH: What guided medieval scholars as they worked out this accommodation?

DL: Augustine (354–430) gave them their principal tool. He had cautioned centuries earlier that Christians should not make fools of themselves by reading their astronomy from the Bible:

Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds as certain from reason and experience.

Now it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people reveal vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh that ignorance to scorn.

By David Lindberg

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #134 in 2020]

David Lindberg (1935–2015), was Hilldale Professor Emeritus of the History of Science at the University of Wisconsin.Next articles

Understanding God through light and tides

Nicholas JacobsonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate