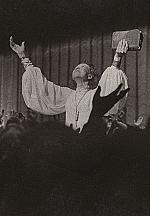

Seeing what Jesus can do

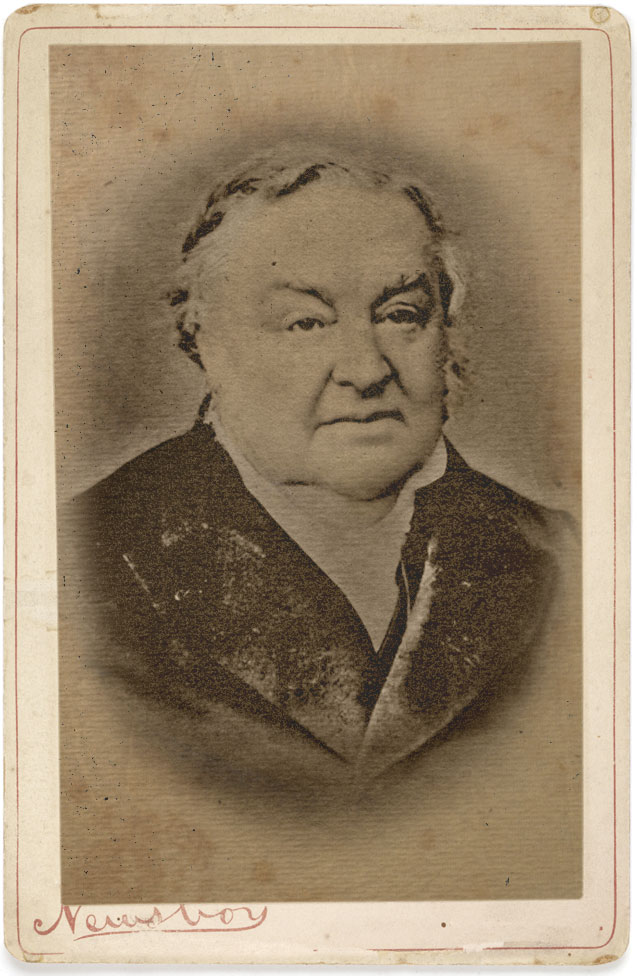

[Above: Johann Christoph Blumhardt the Elder, 19th-c. photograph—Memorial for Johann Christoph Blumhardt / Courtesy of Blumhardt Gesellschaft]

Johann Christoph Blumhardt (1805–1880) did not much care for his parishioner Göttliebin Dittus (1815–1872). The woman was a bother, coming to him repeatedly with disturbing tales of nightly visions. Blumhardt, a Lutheran pastor in the quiet farming village of Möttlingen in southwestern Germany not far from Stuttgart, had more pressing matters to deal with. He even described Dittus as a repellent personality.

But the woman was persistent. When her relatives and the doctor got involved, Blumhardt had little choice but to take her seriously and try to help. In so doing he started something far greater than he had imagined.

Christian history is full of remarkable things happening in out-of-the-way places. The Protestant Reformation began in 1517 in Wittenberg, an inconsequential town in a remote province of the Holy Roman Empire (see CH issue #139). The Pentecostal movement was born in 1906 in an old, ramshackle building in a gritty part of Los Angeles (see pp. 34–37 and CH issue #58). And Christianity itself started in the Galilee region, the backwaters of Roman Palestine.

The healing ministry of Johann Christoph and his son Christoph Friedrich (1842–1919) began in just such an

out-of-the-way place. But their unique understanding of the gospel of God’s reign went on to influence the modern missionary movement, the ecumenical movement, Pentecostalism, the nineteenth-century healing movement, and even Swiss religious socialism. Great theologians such as Karl Barth (1886–1968), Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945), and Jürgen Moltmann (b. 1926) all acknowledged the influence of the Blumhardts on their theology and public witness.

“We have seen enough”

The elder Blumhardt came to Möttlingen in 1838. His first years of ministry were relatively quiet, filled with the basic tasks of rural pastoral life in the nineteenth century. This state of affairs began to change in 1841, when Dittus came to him expressing alarm about her nocturnal spiritual experiences.

After Blumhardt’s initial visit to the Dittus apartment near the village square, accompanied by the mayor and other members of the village council, it became apparent to him that these experiences were of a most nefarious nature. Additional visits confirmed this impression:

It became clear to me that something demonic was at work here, and I was pained that no remedy had been found for the horrific affair. As I pondered this, indignation seized me—I believe it was an inspiration from above.

I walked purposefully over to Göttliebin and grasped her cramped hands. Then, trying to hold them together as best as possible (she was unconscious), I shouted into her ear, “Göttliebin, put your hands together and pray, ‘Lord Jesus, help me!’ We have seen enough of what the devil can do, now let us see what the Lord Jesus can do!”

From this point on, the battle was engaged. For the next 18 months, into Advent of 1843, Blumhardt consistently and tirelessly ministered to Dittus. He would eventually describe strange paranormal activities and phenomena when he reported on the event to his superiors—noting that his only tools for combating the forces holding the woman in bondage were prayer, fasting, and the reading of Scripture. Finally, like the breaking of a fever, on the evening of December 28, 1843, the struggle came to a dramatic conclusion:

The most moving moment came, which no one can possibly imagine adequately who was not an eye or ear witness. At two o’clock in the morning the supposed angel of Satan roared, while [Dittus] bent her head and upper part of her back over the backrest of the chair, with a voice of which one could hardly have believed a human throat capable, “Jesus is Victor! Jesus is Victor!”—words that sounded so far and were understood at such a distance that they made an unforgettable impression on many people.

Now the power and strength of the demon seemed to be broken more with every moment. It became ever more quiet and calm, could only make a few motions and finally disappeared unnoticed like [when] the life-light of a dying person goes out, however not until eight o’clock in the morning.

Jesus is victor

The events connected with the case of Dittus led to a regional revival marked by physical, emotional, and spiritual healings. The town swelled as people came to experience the revival firsthand and proclaim the same rallying cry as Dittus: “Jesus is Victor!” However, the revival caused controversy with Blumhardt’s superiors, and eventually he left Möttlingen for the village of Bad Boll, where a wealthy benefactor purchased a small health spa for Blumhardt’s ministry.

At Bad Boll, Blumhardt established and oversaw a spiritual retreat center, which his son took over after the elder Blumhardt’s death in 1880. Bad Boll became almost synonymous with healing in the German-speaking world, and the ministry of both Blumhardts impacted other movements and individuals in France and the United Kingdom, and even the American healing movement of the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Though the elder Blumhardt has been more readily associated with stories of healing, both Johann Christoph and Christoph Friedrich reflected a great deal on the meaning of healing. Both are described as unpretentious and down-to-earth in their approach, choosing to combine spiritual practices with homeopathic techniques.

They did not develop or use elaborate rituals in their practice. Rather they most commonly employed prayer, fasting, the reading of Scripture, and the laying on of hands in faith. Neither Johann Christoph nor Christoph Friedrich believed that healing is guaranteed, and both stressed that healing is often the result of a process as opposed to a singular intervention.

New heaven and new earth

Three other aspects characterized the Blumhardts’ theology of healing. The most obvious was their recognition that the healing of the body signifies that God cares not only for the soul, but also for the wholeness of each person. The healing of the body, when such an event happens, signifies that God’s concern is for the human person considered as a whole. Salvation includes both the forgiveness of sins and the restoration of our embodied existence.

The second unique aspect of the Blumhardts’ reflections on healing was the conviction that both sickness and healing could be doorways to solidarity with the suffering. When the elder Blumhardt prayed for healing for a specific illness, it became a moment in which to pray for all who suffered from the same illness—indeed for all who suffered in general. Yet many who are sick cannot see past their own pain, much to the dismay of the Blumhardts. Christoph became disgusted by the attitudes of some visitors to Bad Boll in the late nineteenth century; he found them excessively focused on individual needs and desires.

Christoph viewed this myopia as short-circuiting the broader vision and context of healing. His inability to convince people to widen their vision actually led him to stop praying for healing in any sort of public fashion in the 1890s, though he would continue to pray for healing when asked privately.

The last point has to do with the broader context in which the Blumhardts understood the events of healing. For both of them, healing could only properly be understood in an eschatological context. Each event of healing is a provisional sign of what God intends to do for all of creation, when the new heaven and the new earth would finally be unveiled at the end of all things.

When the first events of healing happened in Möttlingen, and then later during the revival and at Bad Boll, they often took Blumhardt and others by surprise. This characteristic gave them an eschatological coloring—these events of healing were signs of the nearness of God’s reign. Johann Christoph Blumhardt stated,

We will be consoled by his compassion because we already see signs of Jesus’s approach: dawn breaks into our night. Many sick will be healed, many of the desolate will receive help, and many will be free who seem overpowered by the enemy! . . . Countless people will recognize that a healing Savior is close by.

As such, to pray for healing is also to pray for the coming of God’s kingdom and the healing of all creation. This hope filled their approach to healing, allowing those who longed for wholeness to see that their desire is connected to the desire of all people, indeed of creation itself, to enter into God’s shalom and experience a truly flourishing life. CH

By Christian T. Collins Winn

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #142 in 2022]

Christian T. Collins Winn is teaching minister and theologian in residence at Meetinghouse Church and adjunct professor of religion at Augsburg University in Minneapolis.Next articles

Marching to Zion

Stories from a nineteenth-century transatlantic faith-healing movement

Joel CabritaChristian History Timeline: The gospel brings healing

Church history is brimming with stories of divine healing; here is a timeline of some featured in this issue

the editorsPower in the blood

Divine healing at the Azusa Street revival and in early Pentecostalism

Gastón EspinosaExtraordinary becoming ordinary

Charismatic renewal and healing prayer in mainline denominations

Amy Collier ArtmanSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate