Jesus was not a white man

THERE WERE MANY SIDES to Howard Jones—musician, pastor, family man, missionary—but as an editor at Christianity Today some years ago, I wanted to interview him about his unique role in evangelical history: in 1957 he became the first African American leader to join Billy Graham’s organization.

Howard Jones’s stoic demeanor when we met reflected the steely focus that carried him through the challenges of being a pioneer of racial progress in America. “It’s an awareness that you’re a living test, a human experiment,” he told me. “Your every word and action has the potential to make or break the hopes of your race.”

When Jones joined Graham’s crusade team, racial reconciliation was decades away from becoming a Christian buzzword, and Martin Luther King Jr. had not yet reached the full height of his fame. Yet, because Jones accepted the challenge of being a “human experiment,” he was a primary case study in Graham’s evolving courage in racial relations.

Playing clarinet and alto saxophone, Jones started off wanting to lead a big band and hoping “to become the next big name in jazz music.” In the late 1930s, big band leaders like Duke Ellington and Count Basie made women swoon, men jealous, and young musicians like Jones eager for a shot at fame.

From all appearances, Jones was a star in the making, but his future wife, Wanda, flipped the script on his planned career. “As a jazz musician, I tended to attract a lot of attention,” he said, “but Wanda attracted mine.” As classmates at Oberlin High School in Ohio, Wanda Young and Howard Jones dated seriously for a couple of years. Then she delivered an ultimatum: put God first or find another girlfriend. “She told me, ‘I love you, but I love Christ more,” he remembered. “‘You keep playing, and I’ll keep praying.’” After several miserable weeks, he came to see things Wanda’s way.

In 1941 the couple enrolled at Nyack Missionary Training Institute (now Nyack College) in metropolitan New York. After graduation they married, and Howard began pastoring Bethany Chapel in Harlem. Drawn to the lost souls outside the church walls, he formed an evangelistic outreach to New York’s inner-city neighborhoods. Along the way, he met Jack Wyrtzen, a bandleader-turned-minister, whose Word of Life youth radio broadcast and evangelistic rallies packed venues like Carnegie Hall.

After eight years in the Bronx, Jones returned to Ohio and became the pastor of Smoot Memorial Alliance Church in Cleveland. There an advertisement in Christian Life turned his attention to Africa. A radio station in Liberia wanted recordings of Negro spirituals produced by African American churches. Their Liberian listeners loved the spirituals. Jones’s church choir recorded some tunes, and the station responded enthusiastically. Jones began sending tapes regularly. They were soon inundated with mail from listeners across Africa who had been converted through the program. “They said it was the first time they had ever heard the voice of an American black man,” Jones recalled.

Soon the radio ministry invited Jones to preach in Africa. So he embarked on a three-month tour, becoming the first African American clergyman to hold major rallies in Africa. “The people went wild,” Jones said. “They beat drums, chanted, and said, ‘Praise the Lord! We’ve seen the white missionary, but we’ve never seen a black preacher from America.’”

Jones believed their enthusiasm disproved the narrow-minded notions American Christians harbored about African missions. “White evangelicals [believed] that Africans would not respond to black American missionaries. We helped change that perception.”

Segregation from Moody to Graham

Jones’s efforts in African missions were groundbreaking, but his most significant contribution to dismantling the church’s cultural prejudices came by way of a letter from Billy Graham.

In the 1950s Graham realized that his integrity as an evangelist would be measured by his response to America’s struggle over race relations. Nearly a full century after the Civil War, Christians in the former Confederate states still balked at integration.

Nineteenth-century evangelist Dwight Moody had confronted the race issue head-on when in 1876 he attracted both black and white audiences to meetings in Augusta, Georgia, but whites began complaining that blacks were filling the best seats. So the rally’s sponsors divided the seating by race. Moody opposed the decision but bowed to white pressure.

In 1917 America’s next superstar preacher—Billy Sunday—held special meetings for African Americans and visited black churches during a campaign in Atlanta. He had been sensitive to the plight of minorities since the start of his ministry as a Bible teacher for the Chicago YMCA. However, he drew the line when it came to holding integrated meetings. He knew that no national white Christian leader who wanted to remain in good standing could upset such social mores.

Billy Graham faced a similar dilemma. During his early years of ministry, he never questioned the custom of segregated seating at his southern crusades. But by 1952 the young celebrity preacher was wrestling with the hypocrisy of racial prejudice in the church. “There is no scriptural basis for segregation,” he told an audience in Jackson, Mississippi. “It may be there are places where such is desirable to both races, but certainly not in the church.”

Blacks and a few whites greeted Graham’s words enthusiastically, but most whites were critical. Under pressure, Graham softened his views. “We follow the existing social customs in whatever part of the country in which we minister,” he said. “I came to Jackson to preach only the Bible and not to enter into local issues.”

Nevertheless, Graham soon realized he could not detach this social issue from his spiritual message. In 1953 Graham stunned the sponsors of his Chattanooga, Tennessee, crusade when he spoke out against segregated seating. There he famously removed the ropes separating black and white seating before one of the meetings. A year later, the Supreme Court banned segregation in public schools. Emboldened by the court’s decision, Billy Graham vowed never again to hold segregated crusades. From then on he began incremental but clear steps toward dismantling segregation in the American church.

But the last thing Jones expected when he returned from Africa in 1957 was a letter from Billy Graham. Graham was then in the early weeks of his 68-day crusade at New York’s Madison Square Garden. He asked Jack Wyrtzen how to reverse the low minority turnout at the event. Graham realized it was important for his rallies to reflect the diversity of his host city, and he was eager to demonstrate his commitment to racial integration. The evangelist had already integrated his team with Akbar Abdul-Haqq, a gifted preacher from India, but he wanted to add an African American. Wyrtzen recommended Howard Jones.

When Jones met the evangelist, Graham greeted him with a warm hug. Graham explained his situation and then invited Jones to join his team. Jones was wary about taking advantage of his church. “I had already been away from my church for three months, so I was afraid that if I asked for any more time off they’d kick me out,” he said.

But when Graham wrote to Jones’s church, the congregation was thrilled to have their pastor “borrowed” by the world’s most famous preacher.

Billy Graham's Jackie Robinson

What came next was tougher. Graham asked Jones to sit on the platform with him in front of 18,000 people. A dozen other pastors and civic leaders sat with them, but Jones was the only African American on stage.

A decade earlier, as the first black player in Major League Baseball, Jackie Robinson had received angry stares and death threats. As “the Jackie Robinson” of Billy Graham’s ministry, Jones didn’t receive death threats, he said, “but I was the recipient of plenty of dirty looks.”

News of Jones’s inclusion on the team brought Graham an alarming number of angry letters. “You should not have a Negro on your team,” they warned. “You’re going to ruin your ministry by adding minorities,” they wrote. “We may have no choice but to end our support.”

“What Billy did was radical,” said Jones. “He weathered the barrage of angry letters and criticisms. He resisted the idea of . . . playing it safe. There was never any hesitation on Billy’s part. . . . He knew it was what God was calling him to do.”

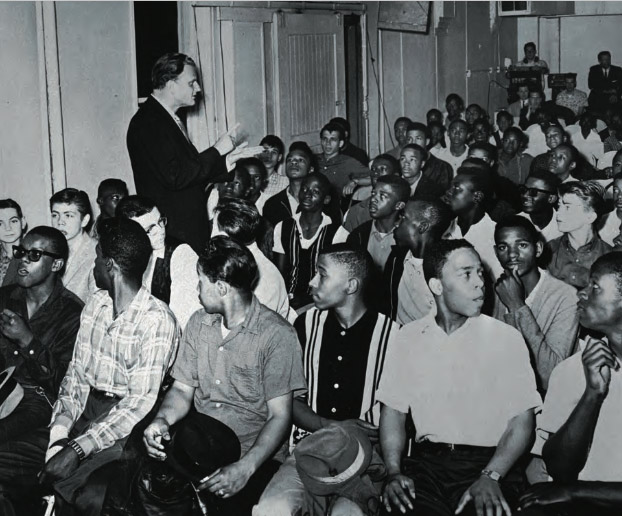

But when Graham asked Jones how to increase minority turnout at the crusade, Jones gave him the hard truth. “If they’re not coming to you, you have to go where they are,” Jones said. “Billy, you need to go to Harlem.”

Many of Graham’s white colleagues said it was too dangerous—“Those savages up there will kill you!”—but Graham knew Jones was right.

“The funny thing is, some of those whites who were saying ‘Don’t go to Harlem’ were members of evangelical churches that were sending white missionaries to Africa,” Jones said.

Jones organized a rally of more than 8,000 people in Harlem, followed the next week by an event in Brooklyn, where more than 10,000 blacks and other minorities came out to hear Graham. The events boosted black attendance at the crusade. By the end of the campaign, blacks made up 20 percent of the 18,000 people who attended each night.

Jones was often the only black person in the room during the long days prior to the evening meetings. And the isolation in the evenings seemed worse. “I remember sitting on the crusade platform on various occasions with empty seats next to me because some white crusade participants had decided to sit on the other side of the stage,” he recalled.

At other times Jones went down to counsel new believers during the altar calls only to see white counselors move away.

Integrating social ministry and evangelism

A year later Jones joined the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) as a full-time associate, serving for more than 35 years, until he retired in 1994. He participated in countless evangelistic campaigns to Africa and elsewhere, helped recruit Canadian evangelist Ralph Bell as Graham’s second African American associate, and was instrumental in various humanitarian initiatives on behalf of the BGEA, raising $80,000 for famine-stricken West Africa in 1975.

“Howard played a strong role in showing Billy the importance of meeting physical needs as well as the spiritual,” Ralph Bell told me in an interview.

During Graham’s 1966 London Crusade, a hotel refused Jones a room because of his skin. Graham told his entire team to vacate the premises and find a hotel that welcomed all races.

In South Africa in 1973, during the height of apartheid, Graham preached: “Jesus was a man; he was human. He was not a white man. He was not a black man. He came from that part of the world that touches Africa, and Asia, and Europe, and he probably had a brown skin.” And then this: “Christ belongs to all people. He belongs to the whole world.”

Jones saw Graham’s boldness up close, and it troubled him greatly when critics, both black and white, questioned the evangelist’s commitment to racial reconciliation and social justice. “I lost a lot of my black friends who thought I should leave Billy,” Jones said. “But the people who accuse Billy of not being vocal enough against racism and other social issues have not seen what goes on behind the scenes. They do not know that man’s heart.”

In November 2010 Howard Jones died at the age of 89. His life was marked by many “firsts” that helped shape racial progress in the modern evangelical movement: first African American evangelist in Africa, first president of the National Black Evangelical Association, first African American inducted into the National Religious Broadcasters Hall of Fame, and first black associate with the BGEA.

Among all those accomplishments, partnering with Graham during the turbulent days of racial unrest in America brought him particular satisfaction.

“In New York, Billy once and for all made it clear that his ministry would not be a slave to the culture’s segregationist ways,” Jones said. “The gospel has always transcended whatever racial or cultural boundaries we’ve constructed to limit it.” CH

By Edward Gilbreath

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #111 in 2014]

Edward Gilbreath coauthored Howard Jones’s 2003 memoir, Gospel Trailblazer. He is executive director of communications for the Evangelical Covenant Church. His most recent book is The Birmingham Revolution: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Epic Challenge to the Church.Next articles

Mama was “a real theologian”

In marrying Ruth Bell, Billy Graham acquired a strong-willed partner, a shrewd father-in-law, and a heritage of Presbyterian purposefulness

Anne Blue WillsConfessor-in-chief

Billy Graham shared the spotlight—and moments of intimate prayer—with more presidents than any other Christian leader

Stephen Rankin“Go forth to every part of the world”

Billy Graham’s early missions to Europe helped shape a global evangelical movement

Uta BalbierWatershed: Los Angeles 1949

The revival that took Billy Graham from anonymity to national fame

Grant WackerSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate