God’s money

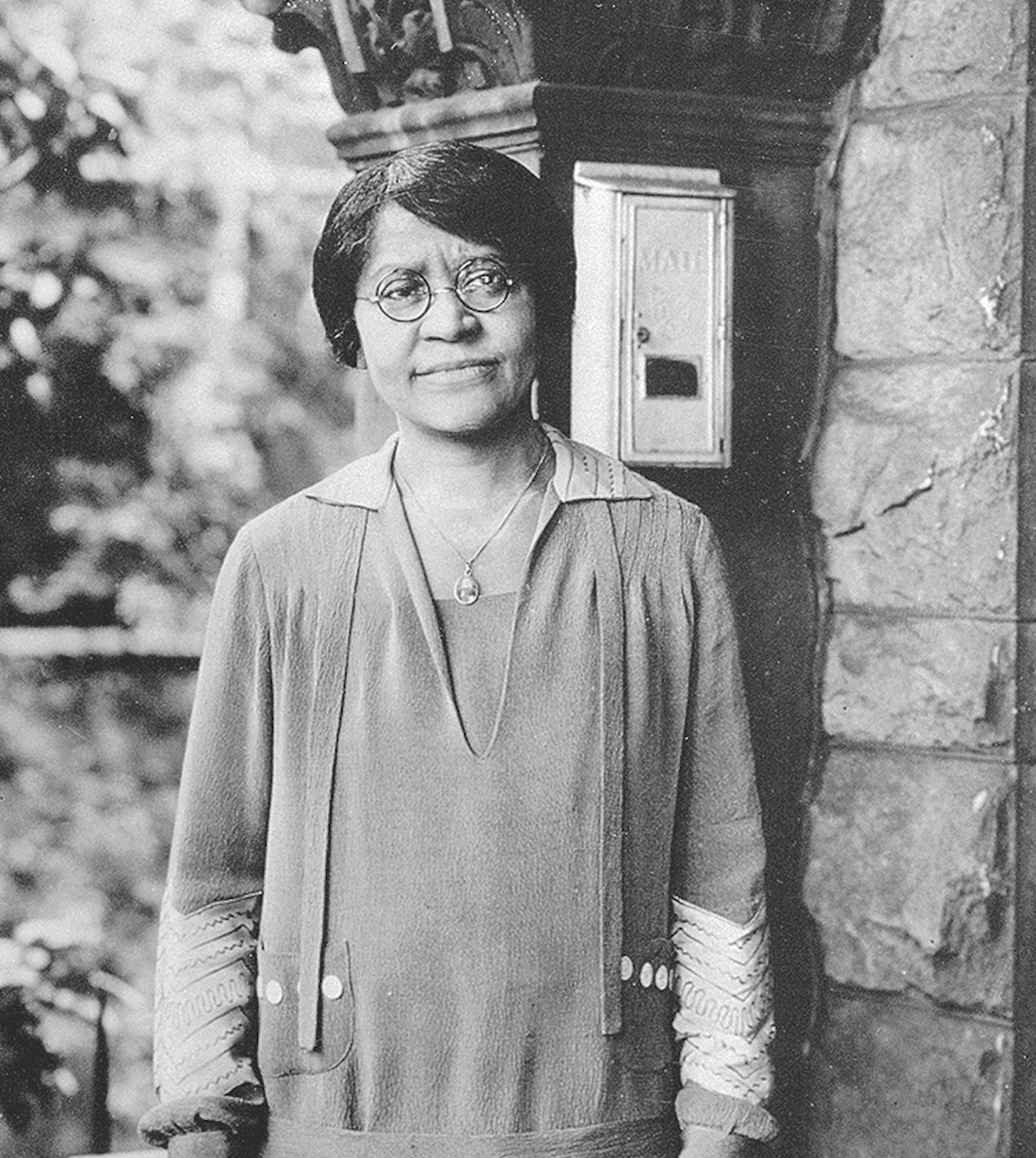

[Annie Turnbo Malone, Chicago History Museum, ICHi-027073—[Public Domain] Chicago History Museum Images]

How influential thinkers have approached business, finance, and the market

Benedict of Nursia (d. 547)

Benedict lived for three years as a hermit before going on to found 12 monastic communities in southern Italy; the influential Rule he gave them has served monastic and lay Christians for over 1,500 years. It provides concise, complete direction for the well-being of a monastery—not only spiritually, but administratively, with advice to everyone from abbot to cellarer.

Benedict divided his monks’ working day into three roughly equal portions: five to six hours of liturgical and other prayer; five hours of manual work, whether domestic work, craft work, garden work, or fieldwork; and four hours reading Scriptures and spiritual writings. All work was directed to making the monastery self-sufficient, with material surplus available to the poor. In times of economic and social distress, Benedictine monasteries served as havens of compassion. This balance of prayer, work, and study has become universally instructive for believers of all ages, cultures, and vocations.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274)

Son of a noble family, Aquinas rejected their plans for him to become a powerful Benedictine abbot, instead joining the up-and-coming Dominican order. His theological thought was capacious enough to include economic wisdom during an era when Italian city-states were emerging as financial hubs and Western Europe was awakening from economic and social slumber. Aquinas saw economic growth as the fruit of a virtuous life lived in community: once basic needs are met, individual Christians should contribute to the needs of their communities. He did not condemn commerce and profit themselves, arguing that communities benefit from the expansion of opportunity and trade.

Aquinas understood the ethics of buying and selling as one part of a virtuous life: the market price was the just price if the buyer and seller were honest and not trying to take advantage of each other. But an ethical problem arises with dishonest participants, especially when the civil law allows or encourages dishonesty. The moral character of buyers and sellers was more important to Aquinas than the act of buying and selling itself. For Aquinas the virtuous man was fair in all his dealings, including economic ones, but could not be virtuous on his own; he needed friends who also love virtue, good laws and customs, and above all God’s grace.

School of Salamanca (15th–16th centuries)

Roman Catholic scholars at the University of Salamanca articulated and debated crucial issues of free trade, natural pricing, property rights, and the role of government in the economy. They included:

• Francisco de Vitoria (c. 1483–1546) believed that the just price is reached by common agreement and that government intervention in trade violates the Golden Rule.

• Martín de Azpilcueta, or “Doctor Navarrus” (1491–1586), built on Vitoria to argue for natural pricing, currency exchange, and the positive integration of profit and human need.

• Diego de Covarrubias y Leyva (1512–1577), student of Navarrus, spoke of the importance of personal property rights, including plant and mineral rights.

• Luis de Molina (1535–1600), a gifted Spanish scholar teaching in Portugal, argued that the value of a particular good is not fixed between people or with the passage of time, but changes according to individual valuations and availability. He also defended retail-wholesale distinctions and private property.

John Wesley (1703–1791)

For more than 50 years, John and his brother Charles led thousands to Christ and helped spearhead movements for the “transformation of manners” (personal ethics and social justice). Some credit the Wesleys with helping England avoid the excesses of the French Revolution. Integrated with the Wesleyan call to pursue personal holiness was the expectation that believers would work for “providential increases” in God’s kingdom in every area of society.

John Wesley believed poverty alleviation began with the opportunity to work for a sustainable income: “Give a man work and he shall have meat.” He also criticized the rich for living lives of luxurious excess, getting richer from government funds and pensions, while their compatriots perished from hunger. Methodists believed all workers should be diligent and honest, but advocated for systemic reforms as well. Wesley’s vision included immediate charity, personal transformation by the Holy Spirit in community, and lasting development as Christian business owners treated workers well and workers offered a full day’s work as worship to God.

Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795)

New factories in the early Industrial Revolution in England were symbols of economic and social progress—and upheaval. Josiah Wedgwood was a pioneer of factory reform, enduring the ire of rivals. The son of a potter, he started in the family business at nine and even as a teenager was designing the fine china for which his factory became known.

Wedgwood was a patrician with stringent discipline. In contrast to his peers, however, he took serious precautions with the work environment. He affirmed that productivity would improve when workers enjoyed fair wages, sanitary housing conditions, and good job training. Wedgwood joined other reformers in working against alehouses, brothels, and cockfighting—replacing these with schools for all, hospitals, orphanages, better housing, and improvements in roads, clean water, and public institutions.

Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920)

Kuyper was a Dutch Reformed pastor, theologian, philosopher, and public servant best known for his proclamation that Christ is Lord over “every square inch” of creation and for his concept of “sphere sovereignty”—arenas where God’s common grace is working toward human improvement and where evil aims at subversion.

Kuyper saw divine ethics as both its own sphere and one that informed all the others, including economics. By the early twentieth century, economics had evolved from a subset of moral philosophy to a “value-free” science in the hands of mostly secular thinkers. Kuyper thought Calvinist principles should underlie, animate, and provide the goal of Calvinist economic science; nevertheless, some room must exist for economics to flourish in its own sovereign sphere, providing insights to contribute to social theology.

Booker T. Washington (1856–1915)

Son of enslaved parents, Booker T. Washington served as an icon of self-determination and dedication to religious and vocational improvement for millions struggling under Jim Crow in the wake of the Civil War and the subverted efforts of Reconstruction. His strong faith informed his personal journey of acquiring an education and founding the prestigious Tuskegee Institute in 1881. From 30 students and poor facilities, it grew into a premier vocational institution with 1,500 students and over 500 acres at the time of his death.

Washington opposed the “agitations” and “extremist folly” he found in W. E. B. Du Bois (see below) and others, preferring gradual economic improvement as the foundation for political rights. He was accused of being too passive and accommodating, and eventually his heart broke over the failed promises of the Wilson administration and the hardening of racial attitudes throughout the South.

W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963)

In 1895 Sociologist Du Bois became the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard. In 1909 he helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and, from 1910 to 1934, served it as director of publicity and research, member of the board of directors, and founder and editor of its magazine, The Crisis. Raised Congregationalist, he was not a faithful son of the church as an adult, though he affirmed its instrumental importance.

Du Bois lauded churches for promoting good morals and assisting in sound business principles but hated their failure to respond to human need: “Today the church is still inveighing against dancing and theatre going, still blaming educated people for objecting to silly and empty sermons—boasting and noise—still building churches when people need homes and schools. . . .” He advocated for legal reforms to overcome social and economic injustice, saying that hope for the future lay in three things: the perception by the intelligent White American laborers of their common cause with African Americans; the hard work and dogged determination of African Americans; and the sympathetic attitude of the country’s elites.

Annie Turnbo Malone (1869–1957)

Malone, daughter of formerly enslaved parents, was a pioneer in multilevel marketing; her entrepreneurial spirit, rooted in deep faith, helped her endure divorce, business competition, and criticism—and unleashed her creativity. She developed haircare products for African American women in her kitchen and began her company with three sales agents and a new strategy: free treatments. Soon she had thousands of agents and purchased a building for her Poro College, Incorporated.

Malone made it possible for her agents to leave demeaning jobs that did not pay well and forged them into a community. She provided them with housing and clothing in a comprehensive communal space that included a bakery, ice cream parlor, and auditorium. It had its own laundry and sewing facility as well as a medical unit that treated students and African Americans in the community.

As her company grew, so did her philanthropy with millions given to a variety of causes benefiting the Black community. She acquired her own supply chain—including a fleet of trucks to deliver her products, because some trucking companies refused to work with her.

R. G. LeTourneau (1888–1969)

From humble beginnings and a seventh-grade education, LeTourneau taught himself engineering and eventually built a manufacturing empire. His earth-moving machines helped win World War II and construct the highway infrastructure of modern America in the 1950s and 1960s. By the end of his life, he held over 300 patents. He also became a leading spokesperson in the lay-driven faith and work movement (see pp. 44–46).

When he was 30 and deeply in debt, LeTourneau’s missionary sister urged him to get serious about serving God. Confused, he assumed he must become a church worker. After LeTourneau attended a revival meeting, his pastor commended his surrender to God’s will and told him God needed his business skills. He decided to make God his business partner and eventually gave away 90 percent of his personal income and stock in the company, reflecting, “The question is not how much of my money I give to God, but rather how much of God’s money I keep for myself.” CH

By Charlie Self

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #137 in 2020]

Charlie Self is director of learning communities at Made to Flourish, ordained in the Assemblies of God, and professor of church history at the Assemblies of God Theological Seminary in Springfield, Missouri. He is the author of Flourishing Churches and Communities.Next articles

God’s kingdom

Interviews with two scholars who study Christians and the Market

Denise Daniels, Brent Waters, and the editorMoney Matters: Recommended resources CH 137

Find more on the history of the church’s relationship with economics and the market in these resources selected by CH’s authors and editors.

The editors and issue authorsBible in America: Did you know?

Bible towns, Bible songs, Bible novels, and pocket Bibles

the editorsBible in America: Letters to the editor

Readers respond to Christian History

our readers and editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate