Drinking from a fount on Sunday

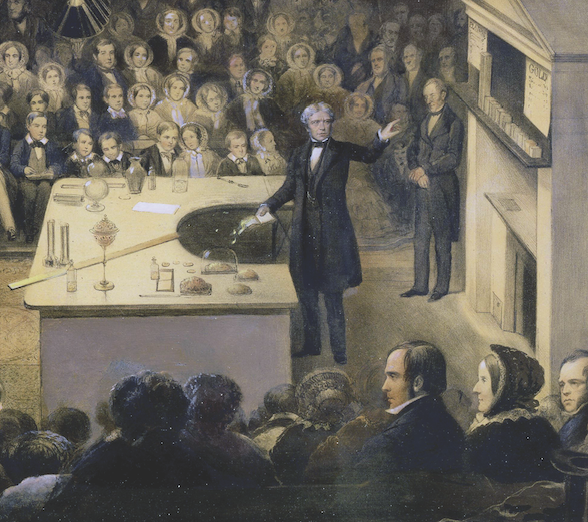

[Michael Faraday (1791–1867) Lecturing in the Theatre at the Royal Institution, c.1856 (coloured lithograph) [detail] / Bridgeman Images]

Michael Faraday (1791–1867) pursued distinctive paths in both science and religion. In science he was largely self-taught, being the son of a blacksmith; he eschewed the more mathematical approach adopted by many contemporaries, especially those with university training. He viewed himself as a natural philosopher, and he did not wish to be described as either a scientist or a physicist—he felt those terms were too utilitarian, focusing on ends above means. In religion he cleaved to a small, dissenting sect—the Glasites or Sandemanians—whose members separated themselves from the established churches and from other Christian denominations.

Primitive Christianity

The Sandemanians trace their ancestry to John Glas (1695–1773). After criticizing the Church of Scotland for failing to adhere to the dictates of the Bible, Glas was suspended from his parish at Tealing (near Dundee) in 1728. He formed an independent congregation and preached what he saw as true, primitive Christianity based firmly on the Bible. Other Glasite communities were soon founded in Scotland; Glas’s son-in-law, Robert Sandeman (1718–1771), helped establish meeting houses in England and later in New England.

Faraday’s father—but not his mother—was a member of the London church of the Sandemanians, which Michael attended as a child and young adult. In 1821, aged 29 and recently married to a member of the congregation, Faraday made his confession of faith, undertaking to live according to the precepts laid down in the Bible and in accordance with Christ’s exemplary behavior. He later served as both a deacon and an elder in the London meeting house.

The roles of deacon and elder were those specified in 1 Timothy 3:2–13; the deacon serving the congregation’s physical needs, while the elder taught and led the congregation. Like other elders Faraday often delivered exhortations—sermons consisting almost wholly of Bible passages. His fellow Sandemanians highly respected him for his piety. However, for a few weeks in the spring of 1844, they excluded him from the church owing to an internal dispute over church discipline. This affected him deeply; he explained to a scientific correspondent, “certain private troubles have brought me low in health and spirits.”

Reliance on the Bible permeated every aspect of Faraday’s life. John Tyndall, his younger colleague at the Royal Institution, remarked that he drank “from a fount on Sunday which refreshes his soul for a week.” He displayed a humble persona and, in line with Christian convictions, distanced himself from many worldly activities; for example he avoided party politics and refused the offer of the presidency of the Royal Society, the foremost position in British science, stating he would “remain plain Mr. Faraday to the end.”

Although a number of Faraday’s discoveries had practical applications that would have made him rich, he did not patent or manufacture any of them. Instead he insisted (in accordance with Matthew 6) that “money is no temptation to me. In fact, I have always loved science more than money.” He also tried to avoid disputes over who had made scientific innovations first and instead viewed the scientific community as “a band of brothers” who should work together to expand human knowledge.

Electric discoveries

Faraday’s scientific career began in 1813 when he was hired to assist eminent chemist Humphry Davy (1778–1829) by performing experiments in the laboratory of the Royal Institution in London. (Davy had damaged his sight in an explosion.) Faraday made several chemical discoveries, including isolating and identifying benzene. However, his first major discovery in electricity was electromagnetic rotation—the rotation of a current-carrying wire round a magnet—in 1821. This later became the basis of the electric motor.

A long series of further electrical discoveries followed, including electromagnetic induction, which underpins the modern transformer and generator. Much of his research was contained in papers read before the Royal Society and subsequently collected in three volumes entitled Experimental Researches in Electricity (1839–1855). Faraday was also a sophisticated theoretician; for example in two insightful papers published in the mid-1840s, he laid the foundation of field theory, which James Clerk Maxwell (see p. 42) subsequently reformulated mathematically.

Through experiment Faraday investigated the structure of the world God had created. Just as he read the Bible carefully and plainly, in his scientific investigations, Faraday read the Book of Nature with similar precision and earnestness. These experiments produced facts which, when collected together and compared, sometimes enabled him to articulate the laws of nature. Believing strongly that “the Creator governs his material works by definite laws resulting from the forces impressed on matter” at the Creation, Faraday sought these God-given physical laws connecting electricity, magnetism, and chemical action. Most famously he discovered laws governing electromagnetic induction and electrochemical decomposition—now known as Faraday’s laws of induction and of electrolysis.

In conceiving of the physical world as God-created, Faraday imported certain religiously based assumptions into his science. One was the widely accepted notion that matter is conserved: the matter that had been formed at the Creation was the same stuff that currently exists, neither depleted nor augmented over time. He also recognized that the quantity of force that God had imparted to matter at the beginning was likewise conserved.

In an 1857 discourse at the Royal Institution, he explicitly supported this conservation of force on theological grounds by arguing that it is “only within the power of Him” to create or destroy force, so force must be quantitatively conserved in all physical processes, though its form may change. For example in a battery, chemical force is converted into electrical force; the quantity of electrical force produced by the battery is equal to the amount of chemical force it loses. (This is not dissimilar to current ideas about the conservation of energy.)

The Royal Institution provided Faraday with living accommodation and a laboratory for his experiments; it also contained a large and imposing lecture hall where he and other scientists gave lectures to members and guests. He delivered a number of Friday evening discourses (including the discourse on the conservation of force) as well as lecture series on scientific topics. He was a highly successful lecturer; one member of his audience noted, “His lectures were ‘mind addressing mind,’ and you felt he was full of sympathy with his audience; and with his fellow creatures.”

History of a candle

In 1825 Faraday inaugurated the Christmas Lectures on scientific subjects, directed to children. These continue to be delivered and are now broadcast throughout the world. Probably the most famous is “A Chemical History of a Candle,” first delivered in 1848 and published in 1861. Often cited as an exemplary scientific text addressed to children, it has never been out of print and has been translated into several languages.

Using the thoroughly familiar example of a candle, Faraday proceeded to show, with simple but impressive experiments, that the candle exemplifies a number of scientific principles. He established a close rapport with the juvenile audience at his lectures, some of whom attributed their later participation in science to Faraday’s influence.

In an 1854 lecture delivered at the Royal Institution before Prince Albert and other dignitaries, Faraday attacked the prevalent contemporary fascination with table-turning at séances, usually explained by evoking a spiritual agency that acted on the table via the hands of the assembled sitters. Faraday argued, using a simple experimental setup, that the movement came from “a quasi involuntary muscular action” exerted by the sitters. Thus to prevent people from being seduced by the fantasies of the spiritualists, he advocated a solid, critical scientific education for all. Faraday also opposed spiritualism as incompatible with his religious convictions, citing the “unclean spirits” proscribed in Acts 8:7.

Faraday died in 1867 and was buried in the unconsecrated area of Highgate Cemetery (the consecrated area being reserved for Church of England burials). In line with the simple Christian values by which he had lived, there was no burial service. His tombstone bore only his name and the dates of his birth and death. In 2006, when an institute for the study of science and religion was founded in Cambridge (UK), it was named the Faraday Institute. CH

By Geoffrey Cantor

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #134 in 2020]

Geoffrey Cantor is emeritus professor of the history of science at the University of Leeds and honorary senior research associate at UCL Department of Science and Technology Studies at University College London. He is the author of Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist as well as many other works on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century science.Next articles

Freedom from dualism

On several occasions Maxwell indicated his view on the relationship between his faith and physics.

Tom Topel“I know that my Redeemer liveth”

George Washington Carver sought to understand God’s creation and develop its benefits for others

Jennifer Woodruff TaitGod made it, God loves it, God keeps it

We talked to four scientists who are believers—three with distinguished careers and one embarking on the journey.

the editors and intervieweesScience and Technology: Recommended resources

Learn more about Christian scientists and inventors throughout church history with these resources selected by this issue’s authors and editors.

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate