“I know that my Redeemer liveth”

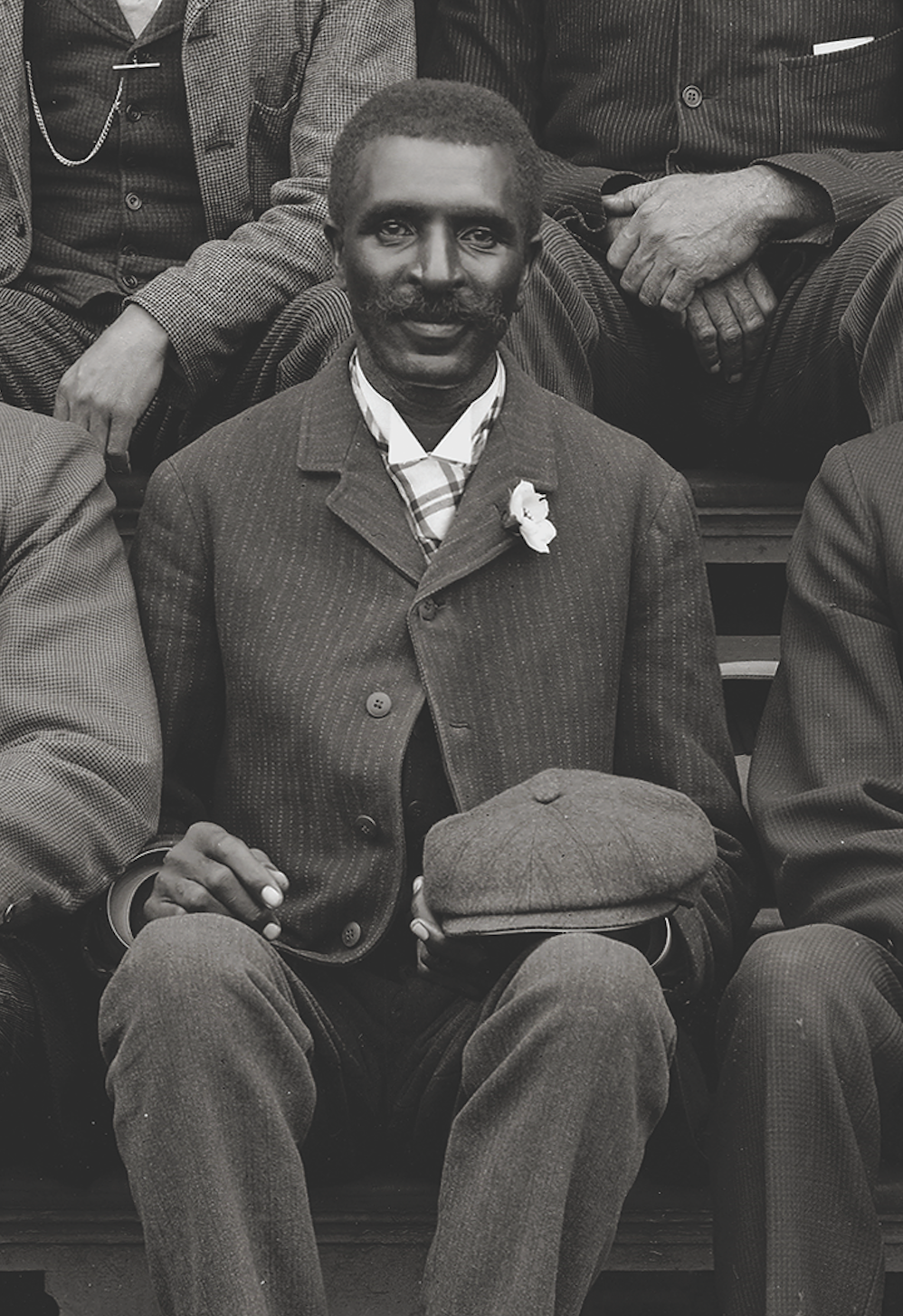

[Carver with Tuskegee Staff Members, 1902—Frances Benjamin Johnston / [Public domain] Wikimedia]

The quiet, unassuming African American scientist in the well-worn suit, flower in his lapel, stood before the House Ways and Means committee in Washington, DC, on January 21, 1921, to speak on behalf of the United Peanut Growers Association. He was granted only 10 minutes, and one of the representatives asked him if he wanted a watermelon (stereotyped as an African American food) to accompany the peanut samples he had brought. He refused the watermelon and soon so enthralled the committee that they let him speak for over an hour and even attended to the brief sermon he concluded with:

If you go to the first chapter of Genesis we can interpret very clearly, I think, what God intended when he said “Behold, I have given you every herb that bears seed upon the face of the earth…” There is everything there to strengthen and nourish and keep the body alive and healthy.

From that day on, George Washington Carver (c. 1864–1943) was known as the Peanut Man. As one of his biographers put it, he had won “a tariff for the peanut industry and national fame for himself.” But peanuts were actually only a small part of his mission.

The name of every stone

Despite Carver’s fame information about his life is difficult to come by. He never knew his birthdate, and although he adopted the middle initial W to distinguish himself from another George Carver, it’s unclear when anyone began claiming it stood for Washington.

Carver was born in Missouri just as the Civil War was ending; his mother, Mary, was enslaved by Moses and Susan Carver. (The Carvers had generally opposed slavery, but they were growing older and needed household help.) When George was an infant, a raiding party kidnapped him and his mother. Moses’s neighbor tracked down George (for which Moses supposedly gave him a racehorse), but Mary was never found.

The Carvers raised George and his brother Jim in their own home; Susan taught the frail George “indoor” skills such as cooking and laundry. When he was 12, his desire for education led him to cross the border to Kansas (public schools in Missouri had largely refused to admit him). He wrote later about his childhood: “I wanted to know the name of every stone and flower and insect and bird and beast. I wanted to know where it got its color, where it got its life—but there was no one to tell me.”

Carver attended school with mostly white classmates. He supported himself by doing laundry, “fooled around with weeds,” tried to homestead, and joined the Presbyterian Church. Highland College accepted him by mail, thinking he was white, but refused to admit him when he showed up. Finally he wound up at Simpson College in Iowa where his natural talent as an artist was recognized. Ultimately he decided to go to Iowa State and study agriculture to benefit other African Americans.

At Iowa State Carver trained as a botanist and agriculturist, studying with one of the nation’s most famous experts in fungi. He also met James Wilson, director of the Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station, who began a prayer group that Carver attended. Wilson recalled that as new students arrived, “Carver and I would sit down and plan how to get boys who were Christians to go down to the depot to meet them.” They became lifelong friends—and Wilson became secretary of agriculture in 1887, the year after Carver graduated from Iowa State.

The chicken yard

The young scientist had several job offers upon graduation, including one to stay at Iowa State. He somewhat reluctantly accepted the invitation of Tuskegee Institute, a new all-black educational institution in Tuskegee, Alabama, headed by Booker T. Washington (1856–1915). Washington wanted badly to begin an agricultural department, and Carver was the best-trained African American agriculturist in the nation.

But the adjustment proved hard. Carver was culturally midwestern, educated in primarily white environments. His demand for one room for him and one for his specimens rubbed other faculty the wrong way. He also battled frequently with Washington. Carver wanted to research, develop a well-stocked laboratory, paint, and mentor. Washington wanted his star professor for more pressing matters: teaching a full load, serving on committees, and managing the Tuskegee experiment station’s farm and chicken yard. The demands of each on the other never really ceased until Washington died in 1915 and his successor released Carver from all teaching except for summer school.

By all accounts Carver was a gifted and engaging teacher, but not systematic. He focused on hands-on collection and study of specimens. Students loved him as a mentor, and in this capacity he started a Bible study on campus in 1907—beginning with a talk on Genesis 1, illustrated as always with his beloved specimens. He taught the study for 30 years, until shortly before his death. He wrote to a YMCA official in 1927 about his students:

I want them to see the Great Creator in the smallest and apparently the most insignificant things. . . . How I long for each one to walk and talk with the Great Creator through the things he has created.

Carver also worked with local farmers to increase sustainability and self-sufficiency. He could do nothing about unjust systems that kept them in debt, but he could do something about soil and crop rotations. He encouraged planting a diversity of crops, using crops in recipes (which he provided), and using local products to beautify homes and yards. His lectures at farmers’ conferences and articles in numerous agricultural bulletins included references to Scripture, such as Are We Starving in the Midst of Plenty? If So Why?, which began with Proverbs 13:23: “An unplowed field produces food for the poor, but injustice sweeps it away.”

This work led to new products made from peanuts, sweet potatoes, and cowpeas, which grew well in Alabama. Carver tried repeatedly but without success to arrive at commercial applications. Eventually the national trend moved toward larger, industrialized agriculture; it would be decades before modern agrarian movements rediscovered his ideas.

“Men of science never talk that way”

After Washington’s death Carver began to spend more and more time away from Tuskegee lecturing. His appearance before the Ways and Means Committee made him famous. He had already been named a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts in London, but he soon collected the Spingarn Medal for Distinguished Service to Science as well as several honorary doctorates.

In 1924 Carver was asked to demonstrate his products at Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan; there he remarked that to facilitate inspiration from God “no books ever go into my laboratory,” which prompted a scathing editorial from the New York Times, “Men of Science Never Talk That Way.” His response circulated informally, arguing that a proper view of divine inspiration would allow that inspiration to influence scientific discoveries. To a friend he wrote that the criticism was directed not at him, but “at the religion of Jesus Christ. Bro., I know that my Redeemer liveth.”

Carver always remained a gifted popularizer and interpreter of science, but as he aged, he grew more distant from mainstream research. His religious fame, though, only grew; many Christians saw his deep and oft-stated faith as a refutation of the atheistic turn they feared was emerging in twentieth-century science. Carver’s faith was truly foundational to his science—both were based in, and constantly renewed by, close observation of the natural world. To his YMCA correspondent he wrote:

Just last week I was reminded of [God’s] omni-potence, majesty, and power through a little specimen of mineral sent me for analysis . . . lo before my very eyes, a beautiful bunch of sea-green crystals have formed and alongside of them a bunch of snow white ones. Marvel of marvels, how I wish I had you in God’s little workshop for a while, how your soul would be thrilled and lifted up.

In 1940, when friends sent him a gift of dahlias, he thanked the great Creator for the gift; God had

made man in the likeness of his image to be co-partner with him in creating some of the most beautiful and useful things in the world. . . . You both are stronger and better from growing these beautiful messages from the Creator.

Many have claimed Carver’s story since his death—fervently if not always accurately. Most recently we have begun to rediscover his ecological wisdom and his Christian mysticism—and to understand that they were intimately related. We would do well to remember him as a man who partnered with God to create things both beautiful and useful from God’s world full of dahlias and sea-green crystals—and yes, even peanuts. CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #134 in 2020]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is managing editor of Christian History.Next articles

God made it, God loves it, God keeps it

We talked to four scientists who are believers—three with distinguished careers and one embarking on the journey.

the editors and intervieweesScience and Technology: Recommended resources

Learn more about Christian scientists and inventors throughout church history with these resources selected by this issue’s authors and editors.

the editorsPlagues and epidemics: Did you know?

Where quarantine came from, how epidemics almost killed Bede and Finney, those beaky masks, and why it’s not “Spanish” flu

Paul E. Michelson and othersSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate