Christianity in the cities, Did You Know

When in Rome. . . .

• All citizens of the Roman Empire had more privileges than non-Romans—think how Paul repeatedly appealed to his privilege as a citizen. But they were divided into social classes by wealth. At the top were the emperors, followed by patricians (wealthy nobility), senators (also wealthy), equestrians (business and military leadership), and plebeians (average working people and rank-and-file soldiers).

• Slaves generally did the most menial work, though some worked as doctors or tutors to children of wealthy families.

• The basic unit of Roman society was the family, and the father, called the paterfamilias, was its absolute head. He could even reject his own children from the family or sell them as slaves.

• Women had no political rights. They could not vote, stand for office, or speak in public. As time wore on, wealthier women gained the right to own property and manage their own affairs; we catch glimpses in the New Testament of some who supported the early church.

• Women were not supposed to appear in a civic capacity, but the interior of the home was considered to be the woman’s domain, and men generally did not interfere with household management.

Life in a Roman city

• Cities were noisy and crowded, with different trades practiced, restaurants and taverns available, and a wide selection of entertainment: circuses, chariot races, plays, athletic games. Many people emigrated from rural areas looking for jobs, which they usually did not find.

• Great marble public buildings dominated the cityscape. Streets were haphazardly laid out until after the great fire (64) of Nero’s reign. People lived in crowded, unsafe tenements called insulae; only the more spacious lower floors of an insula had running water and indoor plumbing. Affluent Romans lived in luxurious multiroom houses (domus). Both insulae and domus had shops or offices in front for conducting business.

• Roman men enjoyed going to the free public baths in the middle of the day, the only place where different classes mixed freely. The baths had areas for exercise, food, and hot and cold bathing. Slaves attended wealthy bathers.

• In the late 200s, Emperor Diocletian gave Rome a bath that covered over 30 acres and could accommodate up to 3,000 bathers. By the year 400, Rome supported over 900 baths.

• All Romans joined in observing dinner at 4 p.m. after visiting the baths; a family would observe rituals to its particular gods at the meal. The wealthy reclined on couches, ate exotic spices, and threw lavish multicourse dinner parties; the poor ate bread and gruel, supplemented rarely with meat, fish, and vegetables. (They received a monthly allowance of grain.)

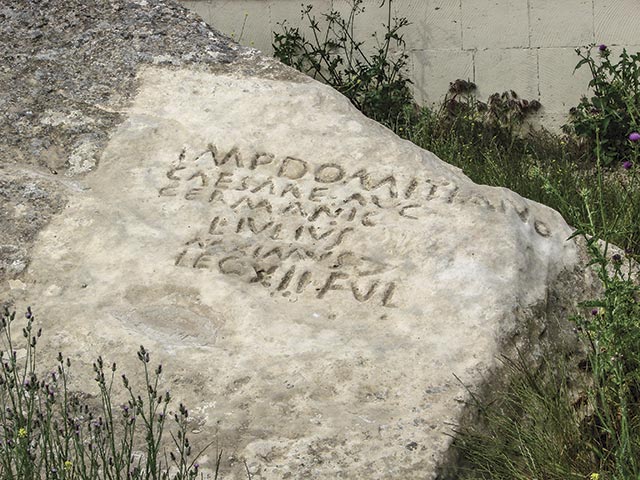

Thundering Legion Inscription. Wikimedia: Grandmaster

Of gods and Christians

• The Roman state maintained colleges of priests and priestesses: the augures, elected for life, studied omens to decide if the gods were pleased; the pontifices helped the emperor in his religious duties; the flamines served individual gods; the rex sacrorum and his wife, the regina sacrorum, spent their lives performing sacrifices for the state; and the vestal virgins oversaw the temple of Vesta in Rome.

• Atheism, one of the leading charges against Christians, meant “against gods” or refusing to participate in the social and civic activities honoring pagan deities. Christian observance of the Eucharist and love feasts also led to accusations of cannibalism and incest.

• Some Romans believed Christians were a funeral society because they observed the anniversary of a relative’s death on the third, ninth, and thirtieth (or fortieth) days after the death. They gathered at the tomb, sang psalms, read Scripture, prayed, gave alms to the poor, and ate a meal. Later this practice developed into feasts to honor martyrs. Perhaps the first such feast was for Polycarp, shortly after his death around 155.

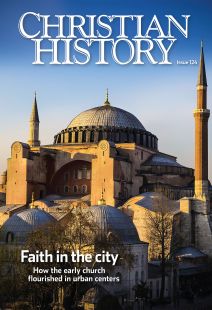

Order Christian History #124: Faith in the City in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Evangelizing pagans

• For more than 150 years, Christians had no official church buildings and worshiped mainly in homes. The first part of worship was open to all, including strangers. The second part of the service involved the Lord’s Supper, which only the baptized could consume; the unbaptized departed.

• Persecution in the Roman Empire was sporadic and, in the first two centuries, usually localized. A long peaceful period lasted from 211 to 303, briefly interrupted by persecutions in 235 and again between 250 and 258.

• Persecution often grew out of animosity rather than deliberate government policy. Faced with persecution, some Christians complied with imperial directives.

• The numbers of those who fell away produced a crisis for the church in the 250s: the question of whether to readmit the lapsed produced several schisms.

• Once legal, Christianity often “baptized” paganism by building churches on old shrines, like San Clemente and Santa Prisca in Rome. The Church of Santa Pudenziana in Rome may be named, not after a martyred Christian, but after Roman senator Pudens who originally owned the land. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #124 Faith in the City. Read it in context here!

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #124 in 2017]

John O. Gooch, retired United Methodist pastor and freelance writer, and Everett Ferguson, distinguished scholar in residence at Abilene Christian University, contributed to previous Did you know? articles from which a few of these entries were taken.Next articles

Letters to the editor, CH 124

Readers respond to Christian History

Editor's note: Faith in the City

Christian city movements, ancient and modern

Jennifer Woodruff TaitLife in the earthly city

Christians advocated for “the Way” in the middle of urban distractions much like our own

Joel C. ElowskyA bishop’s work is never done

During and after persecution, new complexities challenged church leaders

Helen RheeSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate