Christians on trial

HOW DO CHRISTIANS END UP IN PRISON? In many cases their beliefs are at odds with the prevailing government, they are arrested, and they are put on trial. From the earliest days of the church, followers of the Way were tried before Jewish and Roman authorities: not only Jesus himself, but Stephen, Paul, and others. Peter and Silas escaped their famous imprisonment the night before they were to be tried.

A hymn to Christ as to a god

In the early second century, we find one of the first records outside the Bible of Christians on trial before a Roman official. Pliny, the governor of Bithynia et Pontus (in modern Turkey) wrote to Emperor Trajan in the year 112 with concerns about how he should punish Christians who refused to sacrifice to the emperor:

[I]n the case of those who were denounced to me as Christians, I have observed the following procedure: I interrogated these as to whether they were Christians; those who confessed I interrogated a second and a third time, threatening them with punishment; those who persisted I ordered executed….

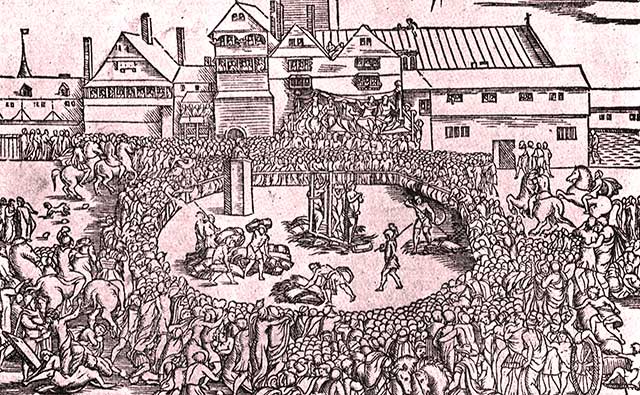

Anne Askew and certain others burn at Smithfield. Walter Besant, London in the time of the Tudors. Adam and Charles Black, 1904.

… They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food—but ordinary and innocent food. Even this, they affirmed, they had ceased to do after my edict by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden political associations. Accordingly, I judged it all the more necessary to find out what the truth was by torturing two female slaves who were called deaconesses. But I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition.

Over the centuries as Christianity was legalized and grew, Christians themselves brought other Christians to trial. By the Middle Ages, an entire system of ecclesiastical courts had evolved alongside of the civil ones. Christians might find themselves in one or the other depending on whether their crimes were theological or practical.

Becoming Protestant

We can explore the experience of being a Christian on trial by examining one woman’s story. Anne Askew (1521–1546) was burned as a heretic in July 1546, late in Henry VIII’s reign. She quickly became a martyr in the eyes of English Protestants, earning a place in John Foxe’s famous Actes and Monuments. But how did a well-connected married Protestant woman and mother end up at the martyr’s stake?

Askew grew up in an influential family in Lincolnshire that moved from staunch Roman Catholicism to committed English Protestantism. Her father, William, knighted by Henry VIII in 1513, accompanied Henry to his famous meeting with French king Francis I at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, and in 1521 became high sheriff of Lincolnshire and a member of Parliament. One of Anne’s brothers was a member of the King’s Privy Chamber; another served in Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s household and was cupbearer to the king; and one sister married twice into well-known Protestant families. Suffice it to say, Anne was well bred and well connected.

In the family’s home county of Lincolnshire, tensions simmered between Protestants and a significant contingent of conservative Catholics. When Sir William Askew enforced royal orders to suppress Catholic religious orders, confiscate property, and levy new taxes to support the royal government, things came to a boil. In October of 1536, a widespread Lincolnshire uprising erupted in defense of the Roman church.

Meanwhile, perhaps against Anne’s own wishes, she had married her older sister’s fiancé, the Catholic Thomas Kyme, after the sister passed away. The couple had two children, but religious differences dogged the marriage. Askew was willing to engage in disputes with Catholic priests, leading Kyme, according to one source, to drive her “violently” away. She never used his name but always signed her writings as “Anne Askew.”

Askew seems to have sued for a divorce, not entirely unreasonable given Henry VIII’s own precedent, but radical for a woman. Her pursuit of a divorce brought her to London, where she appears in the authorities’ records for preaching about her Protestant beliefs in ways that transgressed the Act of Six Articles. Formally titled “An Act Abolishing Diversity in Opinions,” this 1539 act of Parliament reaffirmed traditional Catholic teachings. In March 1545 the London authorities arrested her for the first of three times. Sixteen months later, at 24 years old, Askew was executed at the stake.

By the time she came to the London authorities’ attention, the legal machinery was well oiled for dealing with Protestant heretics, but two competing factions were emerging at Henry’s court. Both were hoping to gain ultimate influence over the king’s heir, the boy Edward, and through that influence to determine the course of the Reformation after Henry’s death.

The conservative Catholic faction hoped that eradicating the Protestant threat in London would strengthen its hold on power; pursuing outspoken people like Askew made perfect sense. The Protestant faction regretted persecution but saw her case as an ideal opportunity to encourage Protestant supporters in London by publicizing what they viewed as nefarious Catholic activities.

Askew herself unwittingly aided the Protestant effort by writing detailed accounts of her time in detention. Her writings about her treatment by the authorities show a woman who viewed her struggle as a small part of a greater spiritual battle. But her supporters easily adapted her words for political use. Printed accounts of her writings circulated widely in London and beyond, some appearing shortly after her execution. She captured the imagination of many sympathetic readers who saw in her the essence of their struggle for the freedom to worship God as they believed they should.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Askew’s trial and prison experiences made for dramatic reading. Her Catholic interrogators hoped to provoke her into admissions of collaboration with the Protestant court faction, but instead she steadfastly held to central Protestant beliefs:

First Christopher Dare examined me at Saddlers’ Hall … and asked if I did not believe that the sacrament hanging over the altar was the very body of Christ really. Then I demanded this question of him: wherefore Saint Stephen was stoned to death. And he said he could not tell. … Secondly, he said that … I [taught] how God was not in temples made with hands. Then I showed him chapters seven and seventeen of the Acts of the Apostles, what Stephen and Paul had said therein. Whereupon he asked me how I took those sentences. I answered that I would not throw pearls among swine, for acorns were good enough. Thirdly, he asked me wherefore I said that I had rather to read five lines in the Bible, than to hear five masses in the temple. I confessed that I said no less. …

Her interrogators, increasingly frustrated with her stubborn refusal to give them what they wanted, grew so desperate that the lord chancellor and another member of the king’s council took control of the proceedings. Unable to extract a confession that she was working with the Protestant faction, they took the highly unusual and almost certainly illegal step of torturing her on the rack in the Tower of London. Even this gambit failed.

Flaming out but living on

As things turned out, the Protestants gained ascendancy after Henry died in January 1547, just six months after Askew’s execution. Boy-king Edward VI’s government adopted as official church teaching the same beliefs Askew had espoused in life and while on trial, and had written about during her incarceration.

Her written accounts proved embarrassing for at least one member of the new royal council who had, in questioning her, demonstrated Catholic leanings. This led to failed attempts to censor Askew’s writings. Faithful persistence in the face of adversity by the woman who once wrote, “With this world will I fight, And faith shall be my shield” would continue to frighten and inspire powerful English leaders for years after her death. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #123 Captive Faith. Read it in context here!

By Dwight D. Brautigam

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #123 in 2017]

Dwight D. Brautigam is professor of European history at Huntington University and co-editor of Court, Country, and Culture.Next articles

Thinking long thoughts

From prison, Christians have produced classic literature that comforts and challenges.

Catherine BarnettParadoxes of prison

For some prisoners, the plunge into the depths became a step heavenward.

Dan GravesSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate