Heel kicking and holy jumping

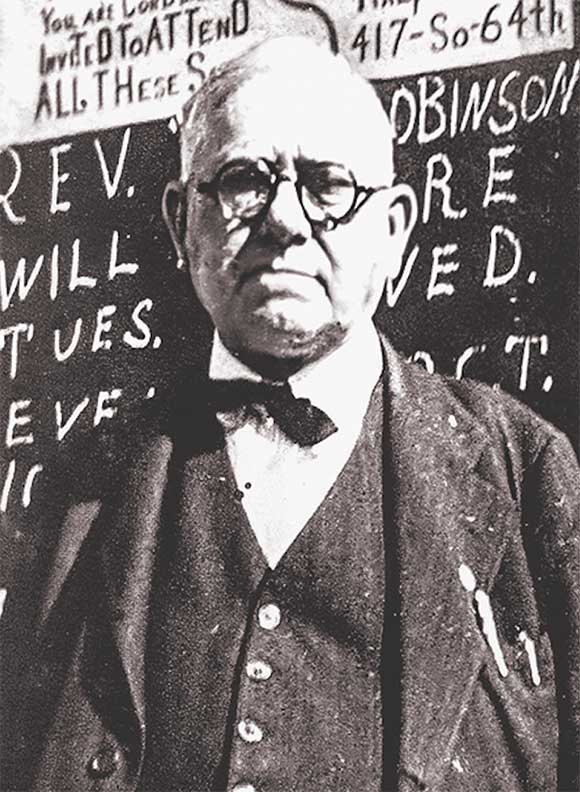

[Rev. “Uncle Bud” Robinson visiting Church of the Nazerene, Bourbonnais, Kankakee, Illinois, Oct 1937—Moses / findagrave.com]

Some early twentieth-century preachers enhanced their oratory with theatrical flair

Professor and social critic Neal Gabler wrote in his book Life: The Movie:

Religion in America not only failed to inhibit entertainment but fed the appetite for it even as its ministers issued futile pronouncements against it.

Referring primarily to evangelical Protestantism’s explosion in the mid-nineteenth century, Gabler identified a new wave of preaching as sermons changed from stern, theological expositions to narrative, theatrical performances containing humorous anecdotes, colloquial asides, and dramatic monologues. Perhaps the best-known example of this, baseball player-turned-evangelist Billy Sunday (1862–1935) used slang, exaggerated gestures, and sensational language as he preached—to the delight of crowds and the annoyance of critics. While some sought to quell this innovation, such tactics were not a mere trend. Theatrical preaching was here to stay.

ENTERTAINING REVIVAL

Though they would likely have bristled at being labeled “entertainers,” nineteenth- and early twentieth-century preachers nevertheless repeatedly used dramatic oratory and even theatrical performance in their ministries. The great Chicago revival and General Holiness Convention of 1901 that saw hundreds converted was a keynote example of performance in the revivalist pulpit. Leaders used both dramatic oratory and elements of stage performance to bring their preaching and (occasionally suspect) interpretations of Scripture to life.

The most colorful of the Chicago evangelists was Andrew “Andie” Dolbow (1846–1934), a reformed New Jersey prizefighter. While preaching Dolbow was known for kicking up his heels, as well as for executing what the Chicago Tribune called “the nearest imitation of a cakewalk that white men are capable of.” (Cakewalks began on southern plantations, where enslaved Blacks exaggerated ballroom dance steps favored by White elites.)

E. A. Ferguson (1869–1912), a former railroad engineer, may have been the perfect complement to Dolbow. Over six feet tall, barrel-chested, and with a booming voice, Ferguson towered over Dolbow, himself barely five feet in height. But both, when overcome by rhythmic music, would engage in a unique dance that vaguely “resembled a vaudeville act.”

JUMP HOW HIGH?

Similarly Rev. John Norberry (1867–1937)—the only one of the Chicago evangelists who held a regular pastorate—used what became known as “holy jumping” to accompany his pulpit rhetoric. Believing anyone who experienced sanctification should be able to jump to their own height, Norberry often leaped from his chair after making that claim. A number of others would immediately join in the action. Norberry also developed a dramatic but effective technique for successful altar conversions—kneeling across from seekers and looking them in the eyes while admonishing them to raise their arms upward while repeating heavenly supplications. Typically that would result in both Norberry and the seeker breaking into spontaneous song or holy laughter.

Finally, less physically demonstrative but no less rhetorically dramatic, were the Holiness stalwarts Seth Rees (1854–1933) and Ruben “Uncle Buddie” Robinson (1860–1942). Robinson, in particular, preferred to use his words to paint dramatic pictures of repentance, regaling the audience with the story of his poverty-ridden Appalachian upbringing, his conversion under the preaching of a traveling Methodist circuit rider after which he flung his gun and deck of cards into the Pecos River, and ultimately his sanctification in a Texas cornfield. Robinson was later referred to as the Will Rogers of the Holiness movement, and his simple, unassuming delivery held audiences spellbound.

Engaging and energizing, the style of these preachers helped fuel their movements as well as influence the preaching of the Word and the formation of religious identity across America. And if we consider the oratory styles of twenty-first-century preachers, no doubt that influence continues today.

By Abram J. Book

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Abram J. Book is assistant professor of communication studies and modern languages at Southeast Missouri State University.Next articles

“Merry Christmas, Mr. Scrooge”

The story includes references to Jesus as the “Founder” of Christmas

Edwin Woodruff TaitFrom drama to life

George and Louisa MacDonald’s family truly lived the Pilgrim’s Progress

Rachel E. JohnsonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate