“Merry Christmas, Mr. Scrooge”

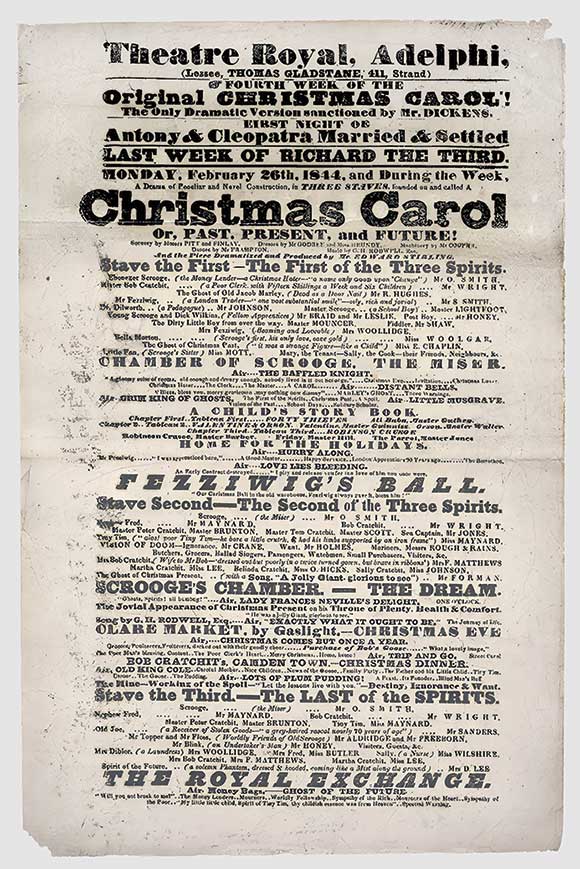

[Playbill advertising A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens at the Adelphi Theatre, London, 1844—British Library / Public domain, Wikimedia]

Every Christmas, theaters around the world perform versions of Charles Dickens’s (1812–1870) novella A Christmas Carol. It has become a staple of modern Christmas—adapted, parodied, echoed in dozens of films and other works. Some writers credit Dickens with “inventing” Christmas as we know it. Even the phrase “Merry Christmas,” though previously in use, became a much more standard greeting after the publication of A Christmas Carol in 1843.

The story’s first theatrical adaptation was performed in 1844; by the end of February of that year, eight different productions ran in London. Dickens himself gave dramatic readings of an abridged version more than a hundred times. The story was first adapted for film in 1901, and many other film versions followed.

CHRISTMAS SPIRIT

In English-speaking Protestantism, Christmas was sometimes as controversial as theater. The Puritans (see pp. 22–24) famously opposed both. Christmas had traditionally been associated with riotous, alcohol-fueled merriment. But in the nineteenth century, a tamer, more middle-class Christmas was developing. Clement Moore’s 1823 poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” famously marked this cultural shift. It cemented the image of Santa Claus as we know it. Dickens’s A Christmas Carol was another marker.

Dickens’s portrayal of Christmas is tinged with nostalgia. One of the novel’s most joyful scenes—often a major centerpiece of theatrical productions—is Fezziwig’s ball. Dickens contrasts this businessman of a previous generation, willing to stop business early and spend money on his workers’ merriment, with Scrooge’s more ruthless and “modern” form of capitalism. Ironically Dickens was singing the praises of a vanished “merry England” while helping create some of the central features of the modern commercial Christmas.

Dickens’s own religious views were rather vague. He expressed love and admiration for Jesus and his teachings, referred to him as the “Savior,” and identified as a Christian. Though brought up as an Anglican, he had no clear church affiliation as an adult and can perhaps best be described as a liberal Protestant of a moralistic and undogmatic sort.

Dickens was fiercely opposed to forms of religion he considered fanatical and dogmatic, including Catholicism and evangelicalism. In the dialogue between Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present, the ghost fills passers-by with Christmas spirit. Scrooge asks why, if the ghost takes such delight in the high spirits of Christmas merry-makers, he would cause shops to be closed on Sundays. While Scrooge’s brand of hard-heartedness is presented as purely secular, Dickens couldn’t resist a side-swipe at evangelical attempts to shutter businesses on Sunday.

GOD BLESS THE OUTCASTS

Still, the story includes references to Jesus as the “Founder” of Christmas and particularly to Jesus as a child. C. S. Lewis argued the story is fundamentally devoid of “any interest in the Incarnation” and that its ghosts are a secular substitute for biblical figures. But perhaps we can read the book’s admittedly vague and nondoctrinal relationship to Christianity another way.

Rather than replacing a traditional Christian understanding of the holiday, Dickens builds on and assumes it. If we really believe God was incarnate as a poor child, how can we continue to live as if money and social status are the ultimate values? How can we shut our hearts to outcasts if we believe the world’s Savior was one?

Adaptations often accentuate the Christian elements of the story. Precisely through the medium of the dramatic arts that nineteenth-century evangelicals regarded with suspicion, a story that criticizes them while holding up a warm and morally transformative picture of the “meaning of Christmas” has become a standard and beloved part of the holiday for many Christians as well as for nonbelievers.

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is a contributing editor at Christian History.Next articles

From drama to life

George and Louisa MacDonald’s family truly lived the Pilgrim’s Progress

Rachel E. JohnsonWizards’ duels and modernist mayhem

Magic, myth, and Christ in twentieth-century theater

Sørina HigginsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate