The spectacle and the spiritual

[Above: Mosaic with scenic masks, 2nd Century AD—Capitoline Museums / Public domain, Wikimedia]

How despicable it is to go from the church of God to the church of the devil . . . to raise your hands to God, and then to wear them out clapping for an actor.—Tertullian

The religious origins of theatrical performances in the Greek and Roman worlds fueled early Christian tensions with the theater. Public theatrical performances emerged in the early fifth century BC. Greek author Aeschylus (c. 525–c. 455 BC), the first dramatist known to us, held performances of his work at the spring religious festival of the god Dionysus on the south slope of the Acropolis hill in Athens. The festival featured religious processions and sacrifices to the god within the theater, and mythological stories about the gods provided the basis for nearly all the Greek tragic plays. Thus, an undeniable link existed between classical Greek tragedy and pagan religion.

Old Comedy, the earliest form of Greek comedy, often made fun of these same stories. In addition, crude sexual humor was a primary feature of these plays, and the performers often wore costumes that exaggerated the sexual organs. Early Greek theater, therefore, both had its roots in a pagan religious context and emphasized bawdy humor.

Roman culture admired and emulated the earlier Greeks in many ways, so it is not surprising that Roman theater was also closely tied to religious festivals. In the Late Republic (second century BC), Rome witnessed a relatively brief period of tragedy and comedy in the Greek style. But by the imperial period (around the time of Jesus), two genres dominated the Roman theater: mime and pantomime. Mimes were comic plays with often ridiculous plots, full of sexual innuendo and vulgar language. Pantomimes were dance performances with musical accompaniment that reenacted stories from mythology.

A DRAMATIC DEBATE

Although mime and pantomime proved to be popular with the public, many Greek and Roman moralists and philosophers condemned theatrical performances because their content promoted moral corruption. This condemnation extended to the performers themselves. Moralists labeled dancers and actors as a disreputable class of society because their disgraceful public displays threatened standards of public morality. The Greek orator Aelius Aristides (117–181) famously wrote a letter to the leaders of the city of Sparta denouncing dancers as threats to the moral health of the city.

Thus Christianity emerged within the context of a lively debate concerning the role of theater in society. On the one hand, these wildly popular shows contributed to a growing Roman imperial culture around mass entertainment (“bread and circuses”). Civic leaders frequently funded performances as part of annual religious festivals and temple dedications. On the other hand, moralists and intellectuals saw these performances as threats to the moral fabric of society because they promoted depraved and foolish behavior.

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–c. 215), a highly educated Egyptian philosopher who converted to Christianity, was the first Christian author to comment specifically on theatrical performances. One of his most famous works, the “Exhortation to the Greeks” (a term used for pagans in general), displayed the folly of many practices of nonbelievers.

He opened with an assault on the mythological roots of theatrical performances. Most dramas, he said, draw their inspiration from the cesspool of old myths about the gods, retold by drunken poets. The plays, he wrote, promote pagan ideas and pull the authors and the crowds that adore them into “the company of demons.” Clement then called upon “Truth, with Wisdom in all its brightness” to shine its light into all these dark places “on those that are involved in darkness.”

WARNINGS AGAINST “SPECTACLES”

Clement’s contemporary in North Africa, Tertullian (c. 155–c. 220), produced the most extensive early Christian diatribe against theatrical performances in “On the Spectacles” (see p. 11). Tertullian believed that theater should be condemned alongside the other primary public spectacles: horse races in the circus, gladiatorial combats, and rituals for the dead (including executions) in the arena. Tertullian understood that Scripture does not specifically prohibit these forms of public entertainment, but he said that the psalmist praises the person “who has not gone into the assembly of the impious . . . nor sat in the seat of scoffers” (Ps. 1:1). From this Tertullian proposed three reasons that Christians should (literally) not sit in seats for shows that “are inconsistent with true religion and true obedience to the true God.”

First, Tertullian exposed how the spectacles originated in idolatrous Greek and Roman traditions. He placed a challenge before any opponents: “If you can show that any of these spectacles has had no connection with an idolatrous god, then I will at once declare it free from the stain of idolatry.” The famous Roman general Pompey (106–48 BC) constructed the first Roman theater on top of a temple of the goddess Venus, quite literally building upon an idolatrous foundation. Because no one could separate spectacles from idolatry, the blemish remained. Christians, Tertullian believed, must renounce these shows because, at the time of baptism,

We make our profession of the Christian faith in the words of its rule. We testify publicly that we have renounced the devil, his ceremony, and his angels.

According to Tertullian, idolatrous entertainment is the work of the devil, so Christians must abstain from it.

Second, public spectacles could spark unholy passions and desires. Tertullian argued that the theater is polluted by “immodest actions and dress that are so strongly and specifically tied to the stage.” He maintained that theatrical shows featuring crude humor and provocative costumes spark physical lust, which Scripture condemns. In fact, “tragedies and comedies are full of bloody scenes and unrestrained behavior; they are the impious and scandalous creators of crimes and lustful thoughts.”

Thus, Tertullian concluded, theater praises whatever is shameful in society and ridicules whatever is honorable. He echoed the concerns of earlier Greek and Roman philosophers, who warned that stirring up the passions would undermine public morality. If arousal might come from these spectacles, Christians ought to refuse them.

The third reason resulted from the previous two. The pagan festivals created a kind of antichurch in which the forces of evil ran wild, Tertullian explained. He began his treatise saying, “How despicable it is to go from the church of God to the church of the devil . . . to raise your hands to God, and then to wear them out clapping for an actor.” Tertullian told two peculiar stories about the fates of those who ventured into this demonic realm. One was an otherwise unattested story involving Jesus himself.

A woman went to the theater and came home possessed by a demon. When Jesus cast out the evil spirit and chastised it for attacking a believer, the demon replied, “I had every right to do this, for I found her in my domain [the theater].” The second story involved a woman who attended a tragedy performed in the theater and had a dream that night in which she saw a linen cloth (probably a burial shroud) and heard the actor’s name said out loud, and five days later she was dead. Tertullian claimed that many such stories exist of those who “spent time with the devil at the shows and fell away from the Lord,” for no one can serve two masters (Matt. 6:24), and light has no fellowship with darkness (2 Cor. 6:14).

Tertullian also mentioned arena spectacles—which involved wild beasts, executions, and bloodshed—and urged Christians to refuse these because they are sometimes the victims. This ominous reality would become far more common and widespread later in the third century.

Tertullian concluded that instead of being inflamed by these shameful spectacles, Christians should be spurred toward the miraculous aspects of the Christian life: treading the devil underfoot, exorcising demons, and receiving divine revelation. If people want blood, he suggested, they should focus on the blood of Christ. And the greatest spectacle of all is the future return of the Lord.

“SHAMEFUL INSANITY”

The writings of Tertullian profoundly influenced the thought of a later fellow North African, Augustine of Hippo (354–430). In his Confessions (c. 400), Augustine reflected on time wasted as a student attending theatrical performances that roused his emotions. As a result of what he called his “shameful insanity,” he took pleasure from experiencing the range of emotions stirred up by these plays, even the negative emotions. Looking back Augustine concluded that these fanciful stories and the passions they provoked comprised yet another distraction that drew his attention away from God, the true object of worship.

While Tertullian is the most famous Latin Christian author to condemn the theater, in the Greek world that distinction belongs to John Chrysostom (c. 347–407). While priest of Antioch in Syria in the late fourth and early fifth centuries, he had many things to say about the evils of the theater.

Chrysostom claimed that some Christians had abandoned the church and neglected their Christian duties because they attended public shows, including the theater. Even clergy and monks had fallen victim. Some Christians had stopped meeting on “the very day on which the sacraments of the salvation of humanity were celebrated.”

Even on Good Friday, “when your Lord was being crucified on behalf of the world, and his sacrifice was being offered, and paradise was being opened,” Christians were attending the spectacles instead of church. If a visitor came to Antioch and asked how this “city of the apostles” had fallen into such spiritual laziness, Chrysostom sadly admitted that he would have no answer.

The shows’ content also concerned Chrysostom, for Christians see things there that could only provoke sexual lust. For instance, as viewers sit in their seats, they would watch “a woman, a prostitute no less, coming onto the stage with her head shaved and no sense of shame. She is finely dressed and flirts seductively with the audience by singing the songs of harlots and using disgraceful language.” Chrysostom wondered if viewers could honestly claim not to be aroused by this. “Is your body made of stone? Or iron? . . . If someone lights a fire in his lap, will he not burn his clothing?” As Jesus had warned in the Sermon on the Mount, anyone who lusts after these women has already committed adultery with them in his heart. And the danger does not end at the theater, for “each man takes home with him much of what he has seen there, so it sticks to him like the infection of a plague.”

SITTING LIKE CRITICS

Moreover, said Chrysostom, attending spectacles creates the expectation of constant entertainment in the minds of many people, and they bring that expectation with them to church: “For the crowds are accustomed to listen [to sermons] not for their benefit but for pleasure, so they sit there like critics at tragedies and musical entertainments.”

Rather than listening to the preaching of the Word of God as a challenge to better their souls, Chrysostom decried, people arrived in church prepared to judge the preacher on his ability to entertain them. Even though congregations reportedly gave great ovations to many of Chrysostom’s sermons, he despised this and saw it as further proof that a destructive mentality had infected the church.

Finally, as Tertullian had, Chrysostom believed that the true theater is the spiritual theater of the church, not the physical theater of the spectacles. The greatest drama is not foolish tales of tragedy and comedy, but the story of God’s redemption playing out in the hearts and minds of believers past and present. He referred to this as “the celestial theater, where the spectators are the angels.”

Early Christian authors feared the negative spiritual impact of the theater on believers. All these authors agreed, however, that it also created a powerful and moving experience in the minds and hearts of those in attendance—in fact, this impact was much of the problem! While drama’s influence drew criticism in the early church, by the Middle Ages, the church began to use those powerful emotional forces in the service of spiritual formation. CH

THE HEBREW BIBLE AND DRAMA

Christianity and theater’s uneasy relationship might be said to have emerged from the synthesis of ancient Hebraic roots and classical perspectives within which the New Testament faith was born. Despite the significance of ritual actions in biblical worship—wave offerings, individual and community cleansings, processions, temple worship etiquette, and so on—there is no Old Testament “drama” to equal similar dramatic enactments and performances in other cultures.

The most obvious contrast is between the Hebrew tradition and classical Greek dramatic festivals. Other cultures too were “theatrical.” Creation myths, redemption narratives, fertility cults—these are the common stock of performances and rituals (if not always full-fledged drama) of most cultural and religious traditions. To some degree they were part of the pagan practices resisted by the Book and people of Moses.

Why this “dramatic” neglect of drama and theater in the Hebrew tradition? The most logical answer is the biblical commandment against images (Exod. 20:4). Representation of birds, animals, humans, and, especially, the gods and Y*W*H, the most High God, was expressly forbidden.

This affected the entire literary nature of the Old Testament and the Jewish religious tradition that produced it (and that, at the same time, it produced). With its emphasis on hearing (rather than seeing), and on memorization and reflective meditation (rather than icons and contemplative meditation), this tradition worked against the development of a highly visual theatrical representation.

God’s words, given in Torah, in the prophets, in the history of his people Israel, were, in their own way, mighty works not to be re-created but to be recited, chewed on, pondered, explained, and, most of all, loved. Psalm 19, which C. S. Lewis calls the greatest romantic poem before Wordsworth, begins with a celebration of the majestic “speaking heavens,” or the revelation of God in nature, but it moves decisively into the central importance of reading, meditating, pondering, obeying, and, most of all, loving the words of God:

The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament sheweth his handywork.

Day unto day uttereth speech, and night unto night sheweth knowledge.

There is no speech nor language, where their voice is not heard.

Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world. . . .

The law of the LORD is perfect, converting the soul: the testimony of the LORD is sure, making wise the simple.

The statutes of the LORD are right, rejoicing the heart: the commandment of the LORD is pure, enlightening the eyes.

The fear of the LORD is clean, enduring for ever: the judgments of the LORD are true and righteous altogether. . . .

Let the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O LORD, my strength, and my redeemer.

(Ps. 19:1-4; 7-9; 14)

—Joe Ricke

By David L. Eastman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

David L. Eastman is the Joseph Glenn Sherrill Chair of Bible at the McCallie School, research fellow at the University of Regensburg and the University of South Africa, and faculty fellow at the Center for Early African Christianity.Next articles

“Not consistent with true religion”

Tertullian penned one of Christianity’s oldest and most famous critiques of theatrical pursuits.

TertullianReforming drama

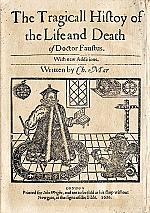

During religious change, English playwrights faced shifting attitudes about theater

Sarah R. A. WatersReading Christ between the lines

Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare wove Christian concepts into their works.

The editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate