The “Philosophy Steamer”

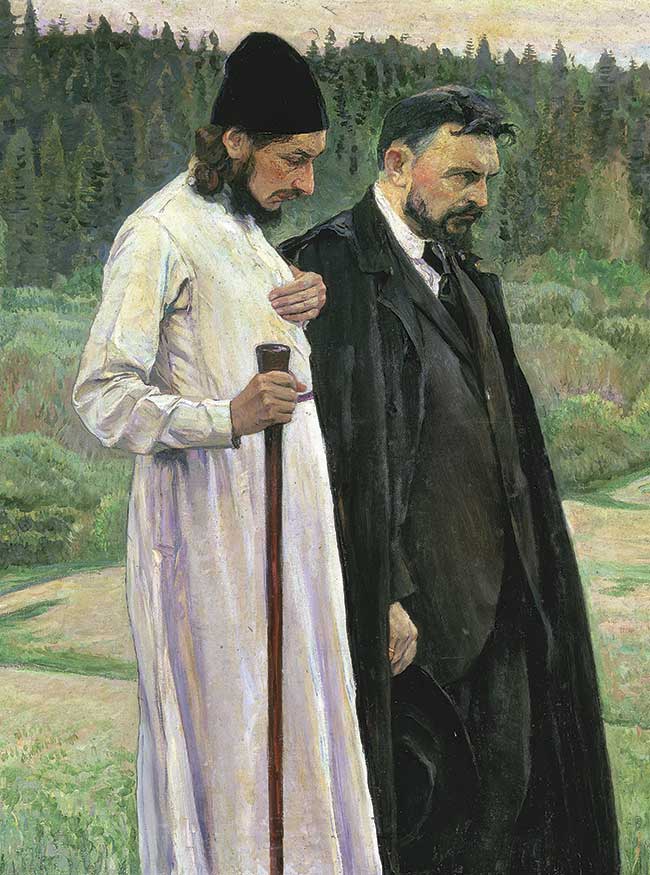

[Mikhail Vasilievich Nesterov, The Philosophers: Portrait of Sergei Nikolaevich Bulgakov (right) and Pavel Aleksandrovich Florensky (left), 1917. Oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia.—© State Russian Museum / Bridgeman Images]

It is the duty of the revolution to put an end to compromise, and to put an end to compromise means taking the path of socialist revolution.—Vladimir Lenin, “Speech on the Agrarian Question,” November 1917

The Bolshevik coup of October 1917 served as a political and spiritual act. Politically it brought a radical Marxist party into power, precipitating a radical break with Russia’s monarchist past. Spiritually the coup involved a rejection of God, the destruction of places of worship, and the expulsion into exile of many influential Russian religious thinkers. These thinkers were expelled on Vladimir Lenin’s direct orders. Because many left by sea, collectively these individuals were known as the “passengers” of the “Philosophy Steamer.” Soviet leaders saw them as the enemies of the communist state and had no use for them.

Those who remained in Russia either died during the country’s Civil War (1917–1923) or perished through the repressive machine of the Soviet state, executed during Stalin’s purges or while languishing in labor camps, the gulags. For the exiled religious intelligentsia, it was a catastrophic experience: they lost their country without any prospect of returning. But it was a catastrophe that saved their lives and brought them together.

The “steamer” brought exiles to the significant cities of Prague and Paris. In Czechoslovakia, the doors of Charles University were opened to them when the Russian Law Faculty was formed in the early 1920s.

Prominent legal scholar Pavel Novgorodtsev (1866–1924) headed its faculty, which included Petr Struve (1870–1944), a political theorist and editor of an important emigre journal, Russian Thought, as well as two theologians: Sergius Bulgakov (1871–1944) and his younger colleague, Georges Florovsky (1893–1979). The latter two would soon move to Paris to collaborate at the newly established St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute. What is known as the “Paris School” of twentieth-century Russian Orthodox theology had St. Sergius as its main institutional center.

Bulgakov: the wisdom of God

A towering figure in Russian religious thought, Sergius Bulgakov experienced a spiritual evolution as complex as that of Augustine. Raised in a clergy family, he lost his faith in his teens, embraced Marxism, became a political economist, then became philosophically dissatisfied with Marxist doctrine. He embraced religiously colored idealist philosophy before eventually coming back into the fold of the Orthodox Church and becoming a priest. His monumental theological system and his literary output are comparable to those of theologians better known in the West such as Karl Barth and Hans Urs von Balthasar.

Bulgakov is best known as an influential representative of Russian sophiology. Founded in the nineteenth century by philosopher and poet Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900), sophiology offered a speculative development of the biblical concept of Sophia, the Wisdom of God. Solovyov identified Sophia with the principle of “Godmanhood,” or divine humanity. Sophia served as a link between God and the world by closing the ontological divide between the uncreated and the created. It was both the ontological ground and the goal of creation, when God will be all-in-all. Bulgakov characterized his position as pan-en-theism, a view that all things were in some sense “in God,” although God could not be reduced to all things.

In the mid-1930s, Bulgakov’s teaching caused a major controversy, the so-called Sophia Affair. Bulgakov faced accusations of pantheism, gnosticism (specifically, for locating the Fall in the divine rather than in the creaturely realm), and a list of other heresies. The de facto head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky), issued an encyclical condemning Bulgakov’s sophiological teaching in 1935.

But Bulgakov’s ruling bishop and the founder of the St. Sergius Institute, Metropolitan Evlogy (Georgievsky), protected him from persecution. With the support of the metropolitan and his colleagues, Bulgakov retained his post. Still, a shadow of heresy continued to hang over his teaching; it remains controversial to this day.

Lossky: God is unknowable

Indeed Bulgakov’s position garnered him enemies among the emigres. The most significant theological opponents included Vladimir Lossky (1903–1958) and Florovsky. In contrast to Bulgakov’s bold speculations about the inner life of the Trinity, Lossky emphasized the apophatic character of Orthodox theology. Apophaticism or apophatic theology insists on the unknowability of God in his essence and describes God in terms of negations: uncreated, unknowable, ineffable, immutable, and so on. In Lossky’s interpretation apophaticism was a refusal to form verbal or mental idols of God; it is a recognition that God is infinitely greater than anything that could be thought about him.

Lossky drew his main inspiration from the sixth-century Byzantine theologian Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, for whom apophatic theology was a form of ascetical theology culminating in the mystical encounter with God. Lossky’s Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (1944) became a classic work that introduced many Western Christians to the treasures of Orthodox theology.

Florovsky: return to the fathers

Georges Florovsky, whose criticism of Bulgakov was less public, announced a “return to the Church Fathers” or the “neopatristic synthesis.” For Florovsky, Bulgakov’s sophiology compromised the centrality of the historical Christ in the Christian tradition.

Florovsky’s neopatristic synthesis was a project to renew contemporary Orthodox theology by retrieving the theological heritage of the Greek church fathers. His retrieval centered on Athanasius of Alexandria’s (c. 296–373) theology of the divine Incarnation, as well as the Chalcedonian Definition adopted at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, which established that Christ is fully God and fully human.

Unlike Bulgakov, Florovsky refused to turn the Chalcedonian Definition into a general metaphysical principle of Godmanhood; he emphasized the historical contingency of creation and the historicity of the divine Incarnation—Jesus had really walked among us, both human and divine. Florovsky’s synthesis of the church fathers became the dominant paradigm of

Orthodox theology, retaining this dominance until quite recently.

After World War II, Florovsky crossed the Atlantic and settled in New York City, where he became the dean of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary and established that institution’s international reputation. Two younger emigre theologians from Paris followed Florovsky: Alexander Schmemann (1921–1983) and John Meyendorff (1926–1992), who became the deans of St. Vladimir’s in succession (see pp. 43–47).

Schmemann: EucharistIc beings

Alexander Schmemann, an outstanding liturgical theologian, became famous for his classic For the Life of the World (1970). Schmemann’s main insight is that humans are Eucharistic beings, mediating creation’s relationship with God in an act of worship. According to Schmemann divine liturgy is an eschatological event, a sacrament of the kingdom.

Schmemann initiated an influential liturgical renewal in the Orthodox Church in the United States and abroad. His theology drew on the “Eucharistic ecclesiology” of Nicholas Afanasiev (1893–1966), who had written “the Eucharist makes the Church.”

Meyendorff: Palamas for today

John Meyendorff became an important translator and interpreter of the work of the fourteenth-century theologian Gregory Palamas (c. 1296–1359). Fundamental to Palamite theology is the distinction between the unknowable and inaccessible divine essence and the knowable and participable divine energies. Like God these energies are uncreated. Access to the divine energies allows human beings to be deified by participating in God rather than in something lesser than God.

For Meyendorff the “neopatristic synthesis” Florovsky had initiated meant primarily the retrieval of Palamas’s theological and spiritual heritage. As a spiritual writer, Palamas provided a theological justification for hesychasm, a monastic movement that placed a great emphasis on the practice of the Jesus Prayer (“Jesus, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner” and variants) and on associated states of mystical union with God.

With Lossky and Meyendorff, Orthodox theology—especially as it came to be expounded in the West—acquired a strongly experiential and mystical tenor.

Berdyaev: Marxism is a cult

No survey of Russian emigre theology would be complete without at least mentioning the name of Nicholas Berdyaev, expelled in 1922. Berdyaev could be regarded as Russia’s most brilliant political theologian. His highly influential book, The Roots of Russian Communism (1937), exposed Russian Marxism as a surrogate religion with its own cult of the martyrs, its own set of canonized writings, its own iconography, its own cult of relics, and so on. As an alternative to Marxist ideology, Berdyaev offered Christian personalism, with its recognition of the uniqueness and value of human beings.

While Berdyaev’s devastating critique of Russian communism and atheism did not penetrate behind the Iron Curtain of the Soviet Union, his work was rediscovered in Russia in the early 1990s and became important for a revival of Christianity during perestroika (a restructure and reform of the Soviet system) in the late 1980s.

Hundredfold harvest

The expulsion of these religious thinkers from Soviet Russia, while tragic and catastrophic, made possible a flourishing tradition of emigre Orthodox theology, which produced a hundredfold harvest. If Orthodox theology is a recognizable commodity in the Western theological academy today, we have the preceding generations of emigre theologians to thank for this development. The greatest temptation of the Orthodox Church’s leadership throughout history has been its co-option by the state (see pp. 16–19 and pp. 49–51). But the Russian exiles of the 1920s and onward could not be co-opted. They continued to oppose the godless Soviet state and Stalin’s idolatrous regime. Russian emigre theology—especially through its critique of the Bolshevik totalitarian state—continues to offer ample resources for resistance. CH

By Paul Gavrilyuk

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #146 in 2023]

Paul Gavrilyuk is professor at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he holds the Aquinas Chair in Theology and Philosophy, and author of numerous books including The Suffering of the Impassible God and Georges Florovsky and the Russian Religious Renaissance.Next articles

A diversity of witnesses

Some Scholars, church leaders, mission workers, and martyrs forming modern Orthodoxy in Russia

Jennifer A. BoardmanQuestions for reflection: Christ and culture in Russia

Orthodoxy in Russia: past, present, future

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate