Remembering and rebuilding

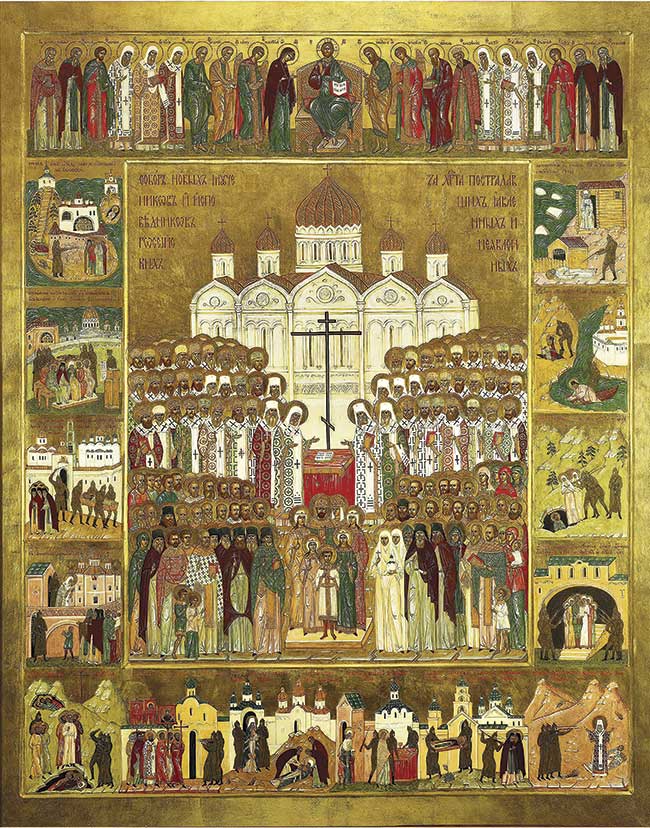

[Saints New Martyrs and Confessors of Russian Church, 2012–2014.]

The 1988 Millennium celebration of the Christianization of Rus sparked euphoria. Communism’s downfall was still three years away, but Orthodox believers within the USSR and abroad saw it as a victory over a state whose ultimate goals presupposed their demise. Yet that milestone celebration was not all it appeared. The Soviet Council of Religious Affairs spearheaded the commemoration to gain support for USSR president Gorbachev’s democratic and economic reforms; only the liturgical participation of thousands of believers transformed it into a public religious moment.

The Council’s director, Konstantin Kharchev, argued that the Communist Party’s decades-long offensive against religion had succeeded. Nevertheless he noted that 10 to 20 percent of the population remained “under the influence of religious views” and thought state policy should be revised to convey that believers were full-fledged Soviet citizens. But the Party did not abandon communist ideals. When the well-known priest Alexander Men was invited to speak on national television in 1989—the first-ever such appearance by a priest—he was not permitted to say “God,” “Christ,” or “Lord.” Instead he quoted Socrates.

Soon the Soviets began returning churches to faith communities and registering large numbers of parishes in Russia and Ukraine. Ukrainian believers who traced their roots to the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC) or the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC, see pp. 12–15) and who had come under Soviet rule during World War II seized the moment. Entire communities proclaimed independence from the ROC and competed for church property. In 1990 the UAOC elected 92-year-old Metropolitan Mstyslav (Skrypnyk) of the United States as patriarch, signaling Orthodox emigre influence.

Concurrently an ROC episcopal council elected Metropolitan of Leningrad Alexy II (Ridiger) as Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus, an Estonian of Baltic-German heritage and son of an Orthodox priest. Adhering to Gorbachev’s principles of perestroika, state officials for the first time in Soviet history did not interfere in the election, even though they had favored Ukraine-born Filaret (Denysenko), Metropolitan of Kyiv since 1966. Filaret returned to Ukraine to take up the cause of Ukrainian autocephaly, which he had previously ardently opposed.

In March 1991 the Soviet state granted the ROC legal status. That November the Soviet council mediating state oppression was dissolved. In December the leaders of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine proclaimed independence from the USSR. With the country unraveling before his eyes, Gorbachev resigned; the Soviet flag over the Kremlin was lowered on December 25, 1991, and the USSR ceased to exist. In its place 15 sovereign states were born—among them Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.

Spiritual colonization

Despite Orthodox Christianity’s seemingly spectacular comeback, things were not quite so straightforward. The Soviet period had left a traumatic legacy.

First, 70 years of totalitarian communist teachings and systemic antireligious policies—a type of internal, spiritual colonization—left millions of Soviet citizens with a worldview antithetical to Orthodox Christianity. Human worth had been measured by utilitarian standards of labor and communist service—in contrast to the Orthodox view of the human person as eternally unique and irreplaceable.

Former Soviet citizens lacked a coherent worldview to guide them in the face of the rapid introduction of market capitalism. Scores turned to once-forbidden, largely forgotten religious roots—Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism as well as Orthodoxy—in search of meaning and belonging.

The spectacular rise in the number of baptisms in the 1990s transformed Orthodox churches into communities of new converts—often including newly ordained parish clergy—who had little lived knowledge about Orthodoxy or the nature of the church. Nevertheless many came with a zeal to become genuinely Orthodox (however that was understood). At the same time, other church leaders came from Orthodox families and had witnessed or experienced repression and humiliation. The effects of trauma, passed down through generations, brought a sense of duty to recover what was believed lost and for some an accompanying sense of entitlement.

Second, 70 years of widespread demolition, looting, and repurposing of sacred property, along with the imprisonment and execution of clergy and lay people, had decimated prerevolutionary Russia’s vibrant Orthodox religious culture (though that culture had not been without problems). Icons, chapels, churches, and places endowed with decades, if not centuries, of prayer and memories were destroyed, and access to liturgical worship was limited or severed, tearing Orthodoxy’s communal fabric. Believers suffered decades of state-induced historical amnesia due to systemic banning of religion-related literature combined with the rewriting of a 900-year past through a Marxist-Leninist lens.

Institutional churches and grassroots believers engaged in the difficult and contentious work of recovery and repair. The late 1980s and 1990s saw a flood of reprints of pre-1917 historical, devotional, religious, and theological literature. Among the main pastoral challenges was the cultivation of a Christian understanding of “church,” not primarily as an institution, but as a mode of being. Rapid institutional church growth complicated this. Desire to display victory over the Soviets by building new churches, or to restore broken ties to ancestors through restoring abandoned or repurposed ones, resulted in an increase from 2,000 to 20,000 active churches in Russia alone between 1991 and 2019. With only three seminaries and two theological academies open in the USSR in 1988, the early 1990s church faced a severe shortage of qualified pastors. Bishops often resorted to ordaining men with little or no formal training.

Due place

The forging of Ukrainian church life faced its own challenges. The surge of UAOC and Ukrainian Greek Catholic communities in its western regions, largely spared the early decades of Bolshevik “ecclesial cleansing” that plagued the eastern and central regions, came with a swell in Ukrainian national identity. In response the ROC granted autonomy to its exarchate in Kyiv headed by Filaret. Supported by Ukraine’s first president, in 1992 Filaret broke with the autonomous UOC and the ROC and established the independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church Kyiv Patriarchate (UOC-KP), which no church in the Orthodox world recognized as canonical. The result was three competing Orthodox churches in Ukraine.

Some church leaders also desired to reclaim a “due place” forcibly denied to them for 70 years. They sensed a silent mandate to demonstrate the church’s relevance and viability in a highly secularized society.

In Russia, Patriarch Kirill (Gundiaev), the son of a priest, whose grandfather spent 18 years in labor camps, was among the most prominent on this front. As early as 1993, as Metropolitan of Smolensk, he founded the World Russian People’s Council, a “meeting place for political, educational, and cultural leaders with different political and religious convictions united by concern for the future of Russia.” Imagining this forum as a contemporary version of a zemskii sobor, a type of civic assembly preceding the reign of Peter the Great, Kirill positioned himself as facilitator of decision-making in the rebuilding of postsoviet Russia’s society.

In Ukraine Filaret—the most vocal, politically connected, and media-present church voice in the country—insisted that the fate of an independent Ukrainian state depended on a single independent Orthodox church. In contrast the autonomous UOC—Ukraine’s only canonically recognized church in the Orthodox world until 2018 and connected to the ROC until 2022—positioned itself as a mediator outside the fray of politics, though supporting Ukrainian sovereignty and an administratively independent Ukrainian church.

Church leaders also promoted nominal and cultural Orthodox identities to reconstitute their flocks and boost “institutional church building.” Prior to 1917 Russia’s imperial subjects were officially identified by confessional belonging. Hence ethnic Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians for centuries belonged to the same identity group. In contrast while the Soviet regime promoted ethnic and national identities, communist ideology defined Soviet identity; believers by definition could not be authentically “Soviet.” Polls reflect a lasting impact. In 2013 approximately 71 percent of Russia’s citizens considered themselves Orthodox, yet only 6 percent found Orthodoxy definitive of ethnic “Russianness.” Only fractions of self-identifying Orthodox claim to participate in the Eucharistic liturgy on a regular basis; some claim not to believe in God.

Fractured histories

The late 1980s and 1990s saw a flood of previously unknown information about Soviet repressions. Former Soviet citizens faced the staggering task of making sense of what Alexander Yakovlev, architect of perestroika, referred to as the regime’s “blood-soaked harvest.” Yakovlev claimed some 20 to 25 million people were executed or died in prisons or labor camps; millions more died in famines; and untold numbers of rank-and-file soldiers and high-ranking military officials were arrested, executed, or deported to Stalin’s forced labor camps as alleged traitors.

Orthodox clergy in Russia routinely speak about the Soviet past in cataclysmic terms—“a horrific ordeal” that “no other people in history has had to endure.” In the late 1980s, many clergy and laity in Russia began to gather evidence about fellow Orthodox victims and to immortalize them as new martyrs distinct from the early church’s martyrs.

The ROC promoted broader civic commemoration of these new martyrs as “heroes of the spirit,” but this met public apathy. Yet Orthodox churches or chapels on mass execution and burial sites—such as the Butovo firing range constructed outside of Moscow where in 1937–1938 alone more than 20,000 people, with backgrounds largely unknown, were executed—elicited some criticism of monopolizing the memory of the repressed dead.

In 2007 the ROC fulfilled a decades-long aspiration of restoring Eucharistic communion with the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA or ROCOR). Established in 1920 during a bloody civil war, ROCOR was comprised of bishops, monastics, parish clergy, and lay believers who fled Russia, hoping some day to return. Never considering itself separate from the ROC and not desiring autocephaly, its self-proclaimed mission was to be the “free voice” of its “mother church in captivity.” When the two reconciled, Patriarch Alexy called it the civil war’s “last chapter.”

But Russia’s and Ukraine’s Orthodox churches still remain divided over rightful heirship to the Kyivan see in Rus. The dominant Ukrainian Orthodox narrative (associated with the UOC-KP and the UAOC) often refers to Kyiv Rus and Ukraine interchangeably. When the Rus of Kyiv were forced to migrate westward following Kyiv’s destruction in 1240, they alone preserved “authentic” Kyivan Orthodoxy in the Galicia-Volynia principality and later in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and thus are the sole heirs to the Kyiv legacy. From this perspective “Russian” Orthodoxy is “other” and threatens the Kyivan-Ukrainian tradition.

A competing Ukrainian perspective (associated with the UOC) views the original Metropolitanate of Kyiv and All Rus as overseeing the vast region stretching from the northern White Sea to the southern Black Sea. In this view the diverse Slavic peoples now known as Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians were all under the jurisdiction of the Kyiv see and equal heirs to that spiritual and ecclesiastical heritage, despite the divergence of their historical fates after 1240 and their formation of three sovereign states in 1991.

The Patriarchate of Moscow and All Rus traces its roots to the Rus legacy through the displaced Kyivan see in Rus’s northeastern region, which Byzantine-appointed metropolitans chose as their permanent residence following Kyiv’s destruction. Based on his own reading of the past, Kirill’s efforts to delineate a Rus-based Orthodox civilizational space as a means of claiming an ecclesiastical jurisdictional sphere of oversight (“canonical territory” including Ukraine) within the broader Orthodox world has become known as his controversial concept of the “Russian world.”

To complicate matters, Postsoviet Orthodoxy’s fractured memory became entangled with the Patriarchate of Constantinople’s own generational memory of trauma since the conquest of Constantinople. In 2019, working with Ukraine’s incumbent presidential candidate (whose campaign slogan was “Army! Language! Faith!”), Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew (Archontonis), acting on his inerpretation of the past, granted autocephaly to a newly-formed Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU), born from a merged UOC-KP and UAOC. The UOC, however, did not join.

In doing so Bartholomew exerted “rights and privileges” granted to the archbishop of Constantinople—since the “New Rome” was the seat of the Roman emperor—by one of the most controversial Byzantine canons among modern Orthodox Christians (the Council of Chalcedon’s Canon 28), He revisited, clarified, and annulled a controversial 300-year-old agreement allegedly transferring the seventeenth-century Kyivan see to the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Moscow, and reestablished his own jurisdiction over that see. The challenges posed by Postsoviet Orthodoxy in Russia and Ukraine have thus laid bare not only seemingly insurmountable divisions among those countries’ Orthodox Christians, but also within today’s “Orthodox world” broadly conceived—caused in part by difficulties in mutually acknowledging, understanding, and empathizing with the long-term impact of the particular traumas its member churches have endured. CH

By Vera Shevzov

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #146 in 2023]

Vera Shevzov is professor of religion and of Russian, East European, and Eurasian studies at Smith College and the author of Russian Orthodoxy on the Eve of Revolution.Next articles

A diversity of witnesses

Some Scholars, church leaders, mission workers, and martyrs forming modern Orthodoxy in Russia

Jennifer A. BoardmanQuestions for reflection: Christ and culture in Russia

Orthodoxy in Russia: past, present, future

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate