Persecution and resilience

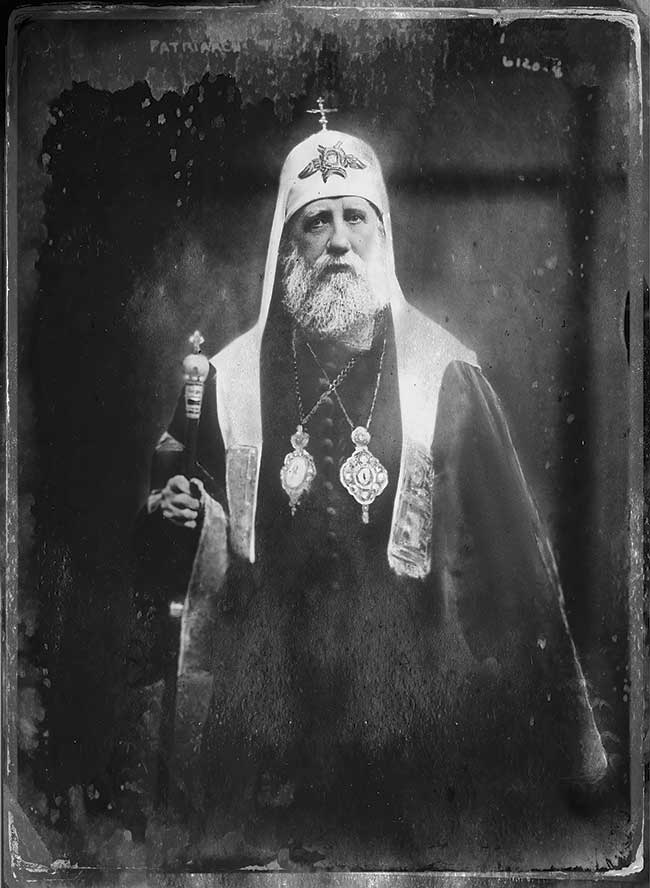

[Above: Patriarch Tikhon, 1900—Bain News Service / Public domain, Wikimedia]

On October 28, 1917, just two days after the communist Bolsheviks seized power, the major All-Russian Council of the Orthodox Church voted to reinstate the office of the patriarchate to head the church. The patriarchate, the traditional hierarchical structure for an Orthodox Church, had been abolished two centuries earlier during the Westernizing reforms of Peter the Great. On November 5 Tikhon (Bellavin, 1865–1925) was chosen to fill the office. As patriarch Tikhon led believers in defending the Orthodox Church from the antireligious policies of the militantly atheist communist regime.

Renewing the body of Christ

Imperial Russia (1700–1917) had legally defined Orthodoxy as the “preeminent and predominant” faith in a multi-confessional empire. As the state church, it enjoyed certain privileges, although other religions generally received broad tolerance, as long as they did not compete with the Orthodox Church for adherents (as did Orthodox Old Believers and Baptists, who were subject to greater restrictions).

Every individual in the empire was legally ascribed to the religion of their birth; furthermore, legal restrictions prevented conversion away from Orthodoxy, though not in the reverse direction. The overwhelming majority of ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Moldovans, and Georgians in the empire belonged to the Orthodox Church (even nominal believers and unbelievers); rates of religious participation in Russia were much higher in the early twentieth century than they were in Western Europe.

The church was also subject to substantial government control and had become rigidly bureaucratized. By the early twentieth century, a renewal movement of laity and clergy sought to regain greater independence for the church from the state; many began to advocate for the restoration of the patriarchate precisely to provide the church with stronger leadership. They emphasized an older ecclesial model focused on the notion of sobornost’ (conciliarism). Sobornost’ emphasized the church as the body of Christ composed of all the members, including the laity, rather than a hierarchical institution tied to the state and consisting of the clergy.

This renewal movement sought fulfillment in an official church council, in which the voice of the entire church could renew ecclesial life stifled by bureaucratization. In the Orthodox Church, the highest authority had always been councils, stemming back to the ecumenical councils of the early centuries. However, because Tsar Nicholas II (1868–1918) feared a church council would result in the restoration of the patriarchate and a greater independence of the church from the state, he prevented a council from convening.

The monarchy collapsed in Russia during the February Revolution of 1917. For the next half year, Russia attempted to establish a modern democratic state, though resolution of key issues was repeatedly delayed because of continued involvement in World War I. Nevertheless the Orthodox Church moved immediately to fulfill the desire for a council. In the spring and summer of 1917, every diocese held a congress of elected members, laity as well as clergy. Those congresses democratized the church (in some cases electing their own bishops, a first for the Russian church) and also elected diocesan delegates for the All-Russian Council of the Orthodox Church.

The council itself began to meet in August 1917. Embodying the notion of sobornost’, laity outnumbered the clergy at the council (299 versus 265 clergymen, including 80 bishops) and had an equal voting voice. The agenda included issues related to virtually every aspect of ecclesial life, from church structure to church-state relations, questions of worship and religious education, and granting a greater role to laity and women in the church.

As the Russian Empire fragmented, some in newly independent territories advocated for an independent (or autocephalous) church as well. There were movements for an independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church, and Georgia reclaimed its ancient autocephalous status (abolished by Russia in 1811).

Because of World War I and the ineffectiveness of the interim Provisional Government, the political situation increasingly destabilized in the fall of 1917. During this time the council debated the first key item on its agenda—the restoration of the patriarchate. Debates about whether it should be restored and how monarchical rule of the church was compatible with sobornost’ continued in September and October, though the unstable political situation by October led the majority of delegates to support restoring the patriarchate.

In this way they could ensure clear leadership in the Orthodox Church at a time when there appeared to be none in the country. Therefore, in its first session after the Bolsheviks seized power, the council resolved to restore the patriarchate—not so much in reaction against the Bolsheviks as from a sense that no stable government was left.

Casting lots

Several days after it voted to restore the patriarchate, against the backdrop of the Bolshevik assault on Moscow, the council held elections. The three candidates with the most votes were Archbishop Antony (Khrapovitsky) of Karkhov, Archbishop Arseny (Stadnitsky) of Novgorod, and Tikhon, who was metropolitan of Moscow. Because no candidate won an overwhelming majority, the council decided to make the final decision by drawing lots among the three, following the ancient tradition of the Alexandrian patriarchate—in effect leaving it in the hands of God.

On November 5, 1917, Tikhon’s name was chosen. Although Tikhon had received the fewest votes of the three, the council was quite divided between the other two candidates; Tikhon’s election served to reconcile the divisions. As one participant commented, Antony was the most intelligent, Arseny was the most strict, but Tikhon was the most kind and good. He was enthroned as patriarch in a grand ceremony on November 21 in the Kremlin.

Tikhon’s unusual career path had included postings on the fringes of the Russian Empire (in Poland and Lithuania) as well as nine years as the Orthodox bishop of North America (see p. 41), where his leadership style modeled sobornost’ through the way he involved his clergy in decision-making and encouraged active lay participation.

Although he had served where Orthodoxy was not the dominant faith and also in places where there was separation of church and state, nothing could have prepared him for what he was about to face. The intensity of the Soviet persecution, far more severe and systematic than the Roman persecutions of many centuries earlier, was certainly one of the fiercest Christianity has ever experienced.

On learning that his name was chosen, Tikhon anticipated that becoming patriarch would not be for honor and glory, but rather he perceived the news like Ezekiel’s scroll, on which was written “lamentation, and mourning, and woe” (Ezek. 2:10).

The Bolsheviks, only one of several socialist groups in Russia in 1917, were the most intolerant of divergent viewpoints and competing ideologies. As Marxists they were materialists and viewed religion as a mechanism by which the ruling classes control the laboring masses. More important, they viewed the Russian Orthodox Church in particular as a direct threat to their hold on power and to their project of building a society ostensibly based on science and reason.

As the Soviets sought to establish their hold on power, the country descended into further anarchy and lawlessness. As a consequence random acts of violence became widespread, committed especially by soldiers brutalized and radicalized by four years of war, now abandoning the front to return home and seize the aristocratic estates long coveted by the Russian peasantry. These random acts of violence were perpetrated not only against the aristocracy, but also against the church and the clergy.

In its first months in power, the Soviet government passed decrees that affected the church indirectly (such as stripping religious weddings of legal status). The first direct assault of the new regime came in January 1918, when the Soviets tried to seize the most important religious institution in Petrograd, the Alexander-Nevsky Lavra. A massive crowd of believers gathered to defend the monastery.

In response to the entire situation, Patriarch Tikhon issued his most infamous encyclical on January 19, 1918, in which he “anathematized” those committing senseless acts of violence. He also criticized some early measures and actions of the Soviet government and called on believers to defend their churches, not with violence, but by being willing to lay down their own lives.

Saving the churches

Many readers conflated Tikhon’s condemnation of random acts of violence with the criticisms leveled at the Bolsheviks. Both the Bolshevik leadership and some within the church, as well as historians since, interpreted the encyclical as a harsh condemnation of the Soviet government per se.

The Soviet regime, as if in answer, issued its Decree of Separation of Church and State on January 23, 1918, which went much further than similar Western decrees. It denied any legal status to the institutional church, deprived it of the right to own property (including church buildings and their contents), and prohibited all religious education in public or private schools that provided general education.

Believers responded to Patriarch Tikhon’s appeals by coming out in the hundreds of thousands for massive religious processions in Moscow, Petrograd, and other cities to express their opposition to Soviet restrictions on religious life. Although in the spring of 1918 some Soviet leaders were willing to negotiate religious policy with the church in response to the massive scale of this opposition, by the summer, as the Civil War intensified, the government took a decisively harsher approach.

In August the Soviets issued instructions for implementing the Decree of Separation that demanded more intense confiscation of church property (bank accounts, land, publishing houses, etc.); church buildings were to be let out on contracts to groups of believers. Unlike Pope Pius X (1835–1914), who had refused to allow lay associations to take control of church properties in France in an analogous situation in 1905, Patriarch Tikhon encouraged believers to take control over their churches; in effect, this saved the church from losing everything and encouraged believers to support and defend their churches.

Incompatible with religion

Throughout 1918 Tikhon tried hard to chart a course that he considered moral rather than political—not condemning the Bolshevik regime directly and not calling for its overthrow, but at the same time criticizing its policies and actions that harmed the church and believers.

In a particularly powerful letter to the Soviet leadership on the first anniversary of the October Revolution, he criticized the Bolsheviks for abuses of human rights as well as their summary justice against suspected supporters of the White Armies during the “Red Terror.” He also criticized their failure to deliver on promises such as peace—having pulled Russia out of World War I, they turned the army’s weapons against their fellow citizens in civil war. The Bolsheviks, however, unable to understand the distinction, regarded any criticism as inherently counterrevolutionary.

During the Civil War (1918–1921), the patriarch refused to take sides but rather condemned fratricidal bloodshed. By the end of the Civil War, the Bolsheviks had secured uncontested political control. But this was not enough; the Soviets sought not merely to transform the Russian political and economic structure but to build an entirely new society in which any competing worldview—including religious ones—would be simply incompatible.

And yet there were many more Orthodox Christians than there were card-carrying Communists. Knowing that Patriarch Tikhon remained the most influential dissenting voice in the country, the Soviets sought a way to destroy this perceived threat to their power. So, in early 1922, Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), one of the Soviet leaders, devised a cunning scheme to accomplish this.

By the end of the Civil War, Russia had been at war for eight years, the economy was in total collapse, and the country was suffering from a massive famine that killed millions of people in 1921–1922. Tikhon rallied believers to voluntarily contribute to famine relief and called on Christian leaders internationally to assist. Such a role for the patriarch, however, was not in the Soviets’ interest. Instead of allowing churches to voluntarily contribute valuable items, they decreed that the state would confiscate whatever its agents decided. Trotsky anticipated that this would cross a red line for the church leadership; as expected Tikhon called on believers not to give up items consecrated for liturgical uses (such as chalices for the Eucharist). It became the easy justification for arresting him and everyone who followed his directive.

Destruction from within?

Under Trotsky’s direction the Soviets handed church administration to a group of left-leaning reformist priests, the “Renovationists,” who in turn declared loyalty to the Soviet government. Thus the regime had created a pretext to discredit church leadership as indifferent to the famine and had suppressed critical and anti-Soviet voices within the church. It now also had a pretext for placing church governance in the hands of the Renovationists and all the wealth from the confiscated valuables (which the Soviets greatly overestimated) at the government’s disposal.

Tikhon was arrested in May 1922 and held under house arrest for over a year while the Soviets interrogated him and prepared for a show trial to demonstrate his guilt and to culminate in his execution. In June 1923, however, they decided to release him—largely due to international pressure—after extracting from him a statement that he was not opposed to the Soviet regime. The Soviets believed this would compromise him, which would be better than making him a martyr.

For his part Tikhon compromised to deter what seemed to him a greater danger—he believed the Renovationists’ control of the church would destroy it from within. After his release the majority of churches and clergy placed themselves again under his leadership. Tikhon spent the last two years of his life trying to restore church unity. He was canonized as a saint and a confessor for the faith by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in 1981 and in Russia in 1989.

After Tikhon’s death the Soviets prevented the election of a new patriarch and arrested those designated to take his place. The church’s de facto leader became Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky, 1867–1944), who in 1927 made a declaration of loyalty to the Soviet Union that caused rifts both at home and between the church in Russia and the church abroad, which remained staunchly anti-Soviet.

Although the Soviets succeeded in leaving the institutional church and its leadership in disarray after Tikhon’s death, the patriarch’s encouragement of lay believers taking control of their parish communities resulted in a grassroots religious revival, especially in the countryside, that persisted through the 1920s, despite active antireligious propaganda.

Darkest moments

But the church’s darkest moments were yet to come. When Josef Stalin (1878–1953) came to power at the end of the 1920s, the regime no longer tolerated only a weakened church hierarchy; local parish communities had to be uprooted. Stalin’s campaign to collectivize agriculture came with a massive closure of rural churches (which had mostly been left untouched until then) together with the arrest or exile of parish clergy. After the 1937 census revealed that over half of the population still believed in God, Stalin concluded that harsher measures were required. He sought to eradicate all “enemies” during the Great Terror of 1937–1938, specifically targeting clergy and religious believers.

The head of the secret police (the precursor of the KGB) reported to Stalin in November 1937 that, after just four months of the campaign, over 30,000 “church people” had been arrested, including 166 bishops, over 9,000 priests, over 2,000 monks, and nearly 20,000 activist believers.

Of those the regime had already executed half the clergy and one-third of the believers, with the rest being sent to the gulag (the prison camp system). As a result the campaign had “almost completely liquidated the episcopate of the Orthodox Church.” He concluded the report by stating more work needed to be done, as there were still thousands more priests and active believers at large—most of whom were suppressed over the course of the next year. The degree of devastation was and is incalculable.

In 1939 the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a secret pact, after which the Soviets occupied territories of western Ukraine, the Baltics, and Moldova. These regions included a large number of Orthodox churches and monasteries, most of which were not suppressed before the Nazis invaded in June 1941. Therefore they did not experience the same kind of destruction and rupture with the past as the rest of the Soviet Union had; many clergy in the postwar Russian Orthodox Church, therefore, came from western Ukraine. The Uniate (Greek Catholic) Church that existed in western Ukraine, however, was completely suppressed and forcibly “reunited” with the Orthodox Church.

The Nazi invasion spared the Orthodox Church from total destruction because Stalin concluded that, to win the war, it would be necessary to mobilize everyone’s support. He therefore reversed his policy toward the Orthodox Church, allowing parish churches to reopen and ceasing antireligious propaganda.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, his successor, Nikita Khrushchev (1894–1971), reinvigorated the antireligious campaign and closed many churches. During the last decades of the Soviet Union, the regime tolerated the Orthodox Church through tight control (since it had eliminated most of the prerevolutionary clergy). Believers suffered close scrutiny and constant discrimination as a result. All the same about one-quarter of the population of the USSR remained faithful.

In the end, thanks to the heroic leadership and example of people like Patriarch Tikhon as well as countless believers who kept the faith alive (see pp. 28–32), Orthodox Christianity outlived communism in the Soviet Union and experienced a remarkable revival after it collapsed. However, the Russian Orthodox Church, like the Russian state, has yet to recover from the Sovietization of its institutional culture. The current patriarch, Kirill (Gundyaev, b. 1946), has not emulated the model embodied by Patriarch Tikhon of a conciliar church drawing its support from believers. Rather he has followed an imperial hierarchical model that seeks support from a close alliance with the state. The result is that today, as in the late Soviet period, the church is under the state’s complete control. CH

By Scott M. Kenworthy

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #146 in 2023]

Scott M. Kenworthy is a professor in the Department of Comparative Religion at Miami University (Ohio). He is the coauthor of Understanding World Christianity: Russia and author of The Heart of Russia.Next articles

Support us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate