ENEMIES MADE ROMAINE PREACH BY A SINGLE CANDLE

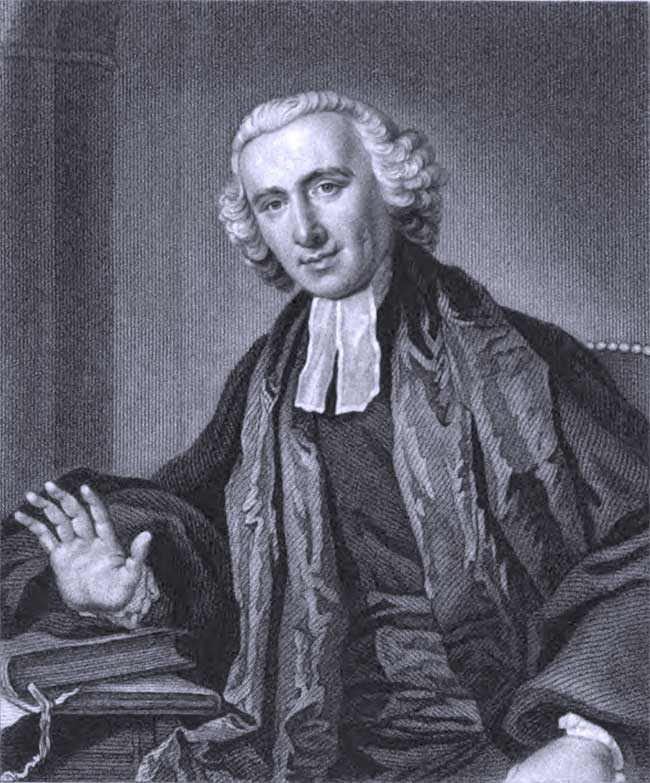

[Above: Frontpiece—Romaine, William. The Whole Works of the Late Reverend William Romaine, A.M. London: Thomas Tegg and Son, 1837. public domain]

ON THIS DAY, 2 SEPTEMBER 1741, William Romaine preached a sermon at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. Titled “No Justification by the Law of Nature,” its premise was that salvation is not possible for anyone apart from the saving blood of Christ, “for holy scripture doth set out unto us only the name of Jesus, whereby men must be saved.” No one can be saved by the light of nature or by earnestly following any human-contrived sect or religion. The sermon was well-received by the Lord Mayor, aldermen, and citizens of London, who urged Romaine to print it.

This appreciation is worth noting because Romaine’s preaching was not always well received before or after that. In the early years of his ministry, this may have been because he was arrogant. In a 1738 exchange with William Warburton, who denied that Moses believed in or taught an afterlife, Romaine was unduly sarcastic.

However, he underwent a conversion around 1745 in which he found peace in Christ and recognized his earlier pride. Writing of himself in the third person, he said, “He met with many disappointments to his pride, which only made him prouder, till the Lord was pleased to let him see the plague of his own heart.”

Romaine had moved to London in 1740 to be near the printers of a Hebrew dictionary and concordance he was revising. The first volume was published in 1747. By 1748 he had packed his belongings to leave the metropolis. A stranger accosted him on the wharf and asked him if he was not of the Romaine family. The man had known Romaine’s father and recognized a likeness. He asked Romaine to accept a lectureship at the combined parishes of St. Botolph and St. George in London.

The following year Romaine was also invited to lecture at St. Dunstan-in-the-West, where two lectureships had been combined into one. Opponents of his gospel raised a fuss and he was stripped of one lectureship and forced to proceed with the other under awkward circumstances, including having to preach by a single candle that he held for himself. Eventually a bishop intervened and conditions improved. Romaine would faithfully lecture at St. Dunstan until a month before his death.

Meanwhile, matters had also grown difficult at St. Botolph and St. George. Romaine resigned in 1755 after seven years of faithful preaching because local householders complained that his sermons attracted too many lower-class people who usurped their seats.

Because Romaine preached justification by faith, he offended many works-oriented leaders and educators in the Church of England. Most notably in 1757, when he preached two sermons on “The Lord Our Righteousness” at the University of Oxford, the school’s vice chancellor, Rev. Dr. Randolph, was so furious that he barred Romaine from ever preaching there again. The printed sermons reveal nothing to offend an orthodox believer.

At times Romaine took positions that other Christians considered with disfavor. For example, he resisted legislation to emancipate Jews in England. Appointed to the professorship of astronomy at Gresham College, he rejected Newtonian physics and the methods and equipment of astronomy because of his interpretation of the Bible. Late in life he wrote against the use of contemporary hymns in church services, insisting that biblical psalms were the only proper texts for worship singing.

However, a lifetime of evangelical teaching and earnest prayer could not to be eclipsed by such vagaries. Romaine developed friendships with many leading evangelicals, including John Newton, George Whitefield, and Countess Huntington. The countess recommended him for the benefice of St. Anne’s (connected with St. Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe), and, after some months in which church politics intervened, he became its rector around 1766. Thus he provided the London area with an evangelical center of worship. By 1774 he was drawing such large crowds a gallery had to be added to St. Anne’s Church.

He remained at St. Anne’s the rest of his life, dying in 1795. His last words were “Holy, holy, holy, blessed and holy Jesus, to thee I commit my spirit.” His biographer William Bromley Cadogan noted that “he appears, never once, in the whole course of [his ministry], to have been corrupted from the simplicity that is in Jesus Christ.” Romaine’s published works, letters, and sermons (which came to less than a thousand printed pages) bear this out. The most popular of them was Treatises Upon the Life, Walk and Triumph of Faith.

Romaine had married Mary Price in 1755 and they had two sons and a daughter. The oldest son, William, became an Anglican preacher. Their son Adam died a decade before his father. The daughter died in infancy.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

Romaine clung to the Psalms for worship. Here is an interpretation of Psalm 27, available at RedeemTV from the Book-by-Book series.