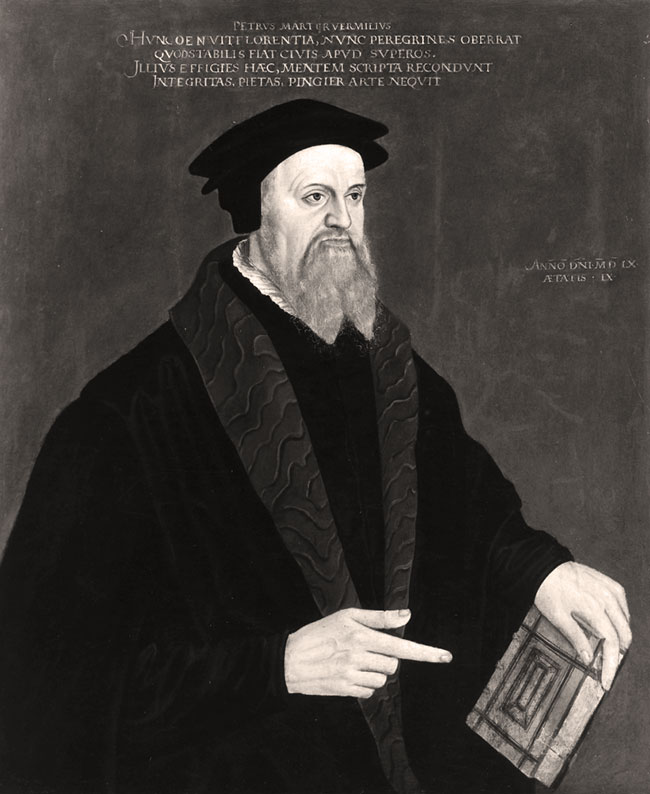

REFORMATION PASSIONS DROVE VERMIGLI FROM PLACE TO PLACE

[Above: Peter Martyr Vermigli. public domain]

PASSIONS RAN HIGH during the Reformation era. When reformer Peter Martyr Vermigli accepted a position at Oxford, he had to erect protective stonework to keep his windows from being smashed at night by angry Catholics. He had broken tradition and brought a woman—his wife, Catherine—to live with him.

A good Catholic himself for the first half of his life, Vermigli was born around 1500 in the solidly Catholic city of Florence in the solidly Catholic nation of Italy to solidly Catholic parents who believed in the intervention of saints. His father insisted on naming him after a saint because several Vermigli children had died in infancy. He hoped that a saint’s advocacy would enable this latest child to reach manhood.

Vermigli’s mother died when the boy was twelve, but not before teaching him Latin. Vermigli determined to adopt a religious life and entered an Augustinian monastery in 1514. Three years later, Luther issued his famous 95 Theses, inaugurating the Reformation. Thereafter, Reformation ideas influenced Vermigli. More than once the tumultuous events of that epoch altered the course of his life.

Vermigli showed so much promise as a student that the Augustinians sent him to Padua where he would study at the university for eight years. Determined to read Aristotle’s works in their original language, he taught himself Greek. When he was twenty-seven, the Augustinians commissioned him to preach, and he moved from convent to convent to do so. While at Bologna, he learned Hebrew from a Jewish doctor.

Continuing his progress, at thirty Vermigli became an abbot at Spoleto. He handled himself so well, he was promoted to a better-known abbey in Naples. There he read Reformation literature and began a dangerous association with the religious reformer Juan de Valdés. His preaching took on a deeper and more evangelistic tone.

Soon Theatines (an order recently founded to combat Lutheran ideas) accused Vermigli of heresy. Viceroy Toledo commanded him to cease preaching. However, Vermigli had reform-minded friends among the cardinals in Rome and they persuaded the pope to overturn Toledo’s ruling. Following a bout of sickness, Vermigli transferred to Lucca. Lucca’s cardinal-bishop was no friend of the Reformation and began proceedings that Vermigli knew would not end well for him given the charged climate of the day. He fled.

By 1542, he had joined the German reformers and was teaching in Strasbourg, where he married Catherine, a nun who had left her convent. In 1547, he accepted Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s invitation to help in England. Appointed Regius (royal) professor of divinity at Oxford, he had to deal with the broken windows already mentioned. While in England, he participated in a four-day disputation, defending a view of the Eucharist closely resembling that of the Swiss Reformers. Near the end of Edward VI’s short reign, Vermigli helped produce the English prayer-book’s 1552 version. He also suggested edits to the 42 Anglican articles of faith that became today’s 39 Articles and he assisted with revisions of English church law.

Following Edward’s death, Queen Mary restored Catholicism and placed Vermigli under house arrest. Eventually she let him leave England. Catherine Vermigli had died and was buried in England, but remained at the center of the passions of the day. Archbishop Reginald Pole exhumed her body on suspicion of heresy and buried it in a dung hill. (Queen Elizabeth I would later restore Catherine’s bones to the churchyard and mix them with other bones to dissuade anyone from exhuming them again.)

Vermigli returned to Strasbourg. Growing tensions between Lutheran and Swiss teachings on the Eucharist caused him to relocate to Zurich where he taught Hebrew. He remarried. His second wife was also named Catherine. They lost their first two children in infancy. Meanwhile, Vermigli continued active in the Reformation. At the Colloquy of Poissy in 1561, he defended a Reformed view of the Eucharist against Catholics. But worn out, he died in Zurich on this day, 12 November 1562. Soon afterward, Catherine delivered a daughter, Marie, who lived to adulthood and married.

For over a decade, Vermigli was remembered primarily for his writings on the Eucharist and for a number of masterful commentaries on books of the Bible. That changed when Robert Masson published Loci Communes (Commonplaces), compiled from Vermigli’s notes. Oddly, Masson arranged Loci Communes using the pattern of Calvin’s Institutes. This book went through many editions, and was often consulted by the second generation of reformers. Nonetheless, Vermigli fell into obscurity and was overshadowed by Calvin for centuries. That obscurity is now lifting and scholars speak highly of Vermigli’s originality and his influence on other theologians of the Reformation.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more on the Reformation, watch This Changed Everything at RedeemTV.

(This Changed Everything can be purchased at Vision Video.)

For more on Vermigli, read "A motley, fiery crew" in Christian History #118, The People's Reformation

Contemplate the story of the Incarnation day-by-day throughout the season of Advent in our latest publication, The Grand Miracle. Based on the writings of C. S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, George MacDonald, Dorothy Sayers, and others, each day’s reading offers a fresh look at the birth of Christ through the eyes of a modern author. Scripture, prayer, and full-page contemplative images complete each entry. 28 days, 64 pages. Preview the Devotional here.