STACKHOUSE EXPOSED BISHOPS WHO EXPLOITED CURATES

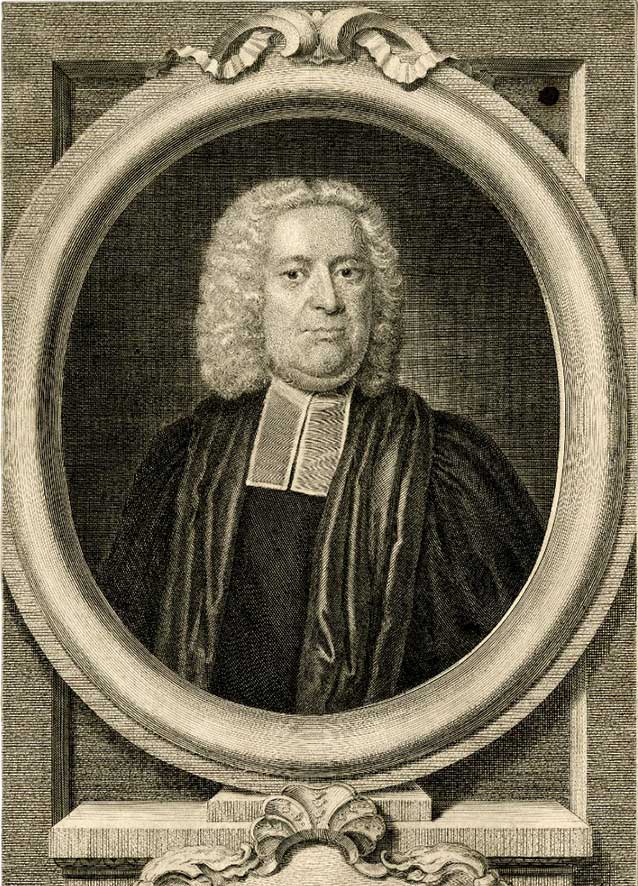

[Above: Thomas Stackhouse—1743 engraving by George Vertue, after John Wollaston. Wikimedia. Public domain.]

FROM TODAY'S VANTAGE, Thomas Stackhouse seems a minor figure in the religious events of his age, but his life and work illuminate two major aspects of his day: the inadequate provision made for lesser clergy in the English system and the growing skepticism of the educated classes.

In an open letter Miseries and Great Hardships of the Inferior Clergy (1722), which Thomas Stackhouse addressed to John Robinson, the Lord Bishop of London, he complained that many clergy in higher office lorded over, humiliated, and misused their subordinates. Some bishops refused to license curates (members of the clergy employed to assist rectors or vicars) so as not to be at the expense of providing the salary the law required. By robbing them of fair remuneration, they forced them into dire financial straits (laws restricted the endeavors from which clergy could earn outside income) and tempted them to preach inoffensive messages rather than denounce real sins and arouse the anger of shopkeepers to whom they owed money, or gentlemen at whose tables they relieved their hunger:

We have the Happiness, or Mortification shall I call it, my Lord, to live in a Kingdom, where we see Deputies of all sorts better provided for in point of Allowance, and Servants of all Kinds better secur’d against the Oppression of their Masters, than ’tis our Fate to be....

Stackhouse was well acquainted with poverty. His father was a curate whose limited means prevented the son from completing a degree at the University of Cambridge. Although he was a diligent student, he had to withdraw from college. Stackhouse became headmaster of Hexham grammar school in 1701 but left in 1704 for London which had greater opportunities for scholarship and publication. Ordained a priest, he held no settled position for several years, but assisted more fortunate brethren where needed. “In this Capacity I lived sometimes in Town and sometimes in the adjacent Country officiating as Curate [for] such, as had better Friends or Fate than myself.”

Despite his paltry income, he married. His first wife died in 1709, leaving him three children, including a son also named Thomas. His second wife would also bear him three children. In 1713 he was appointed minister of the English Church in Amsterdam. However, he did not remain long:

Not much delighted with the Air and Manners of Holland, I returned to London again, and set myself down in earnest to a regular Course of Study, for hitherto I had made Books my Amusement only in that Part of Learning more especially, which (as a Divine) I thought myself concerned to know.

From then until he was made rector of Beenham, Berkshire, in 1733, he held low-paid curacies and earned what he could from his publications, but, as he pointed out in Miseries, the writings of a curate were not such as generally make one rich: “But Sermons, alas! who will read them? a Baker's Dozen for Twelve Pence!”

Of Stackhouse’s many writings, three stand out: his Miseries, already mentioned; an abridgement of Bishop Gilbert Burnet’s popular History of His Times, and a history of the Bible, aimed at refuting the anti-biblical assertions of the day’s proliferating skeptics. Critics agree its greatest strength is in its summaries of his antagonists’ positions.

Late in life the patronage of a powerful bishop enabled Stackhouse to devote more time to literary projects. Stackhouse died at Beenham on this day, 11 October 1752, and was buried in the parish church.

—Dan Graves