SOR JUANA INÉS CHOSE THE PATH OF LEARNING AND WON HONOR

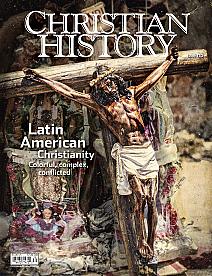

[Miguel Cabrera (1695–1768), Portrait of sor Juana Ines de la Cruz in her library.—Nameneko / [public domain] Wikimedia File:Sor Juana by Miguel Cabrera.png]

JUANA RAMIREZ DE ASBAJE was born with a strike against her: she was illegitimate, euphemistically called a “daughter of the church.” Her father was a Spanish captain who ignored her existence, but thanks to her maternal grandfather she grew up in easy circumstances and exposed to books. The year of her birth is uncertain, usually pegged as 1651 (when she was baptized) but perhaps as early as 1648. She was reading and writing Latin by the age of three and would go on to learn Greek and Nahuatl (an Aztec language). She is supposed to have learned to keep accounts at five. At eight, she wrote her first poem. Poetry would be the category of composition in which she would be most facile.

Juana earnestly desired learning. As a teen she pleaded to be allowed to dress as a boy so she could take university classes but her family said no. Meanwhile she taught herself every subject that scholars commonly learned, taught other girls Latin, and made an impression on her contemporaries. At sixteen she became the companion of the Viceroy’s wife and at seventeen she impressed a delegation of forty scholars with sound answers to a wide range of questions.

Suitors sought her hand because she was attractive, but she preferred a path that would enable her to pursue learning. At first she entered the Monastery of San Jose (St. Joseph) but soon left it for Santa Paula, a Hieronymite monastery, named for the female sponsor of the great biblical scholar Jerome who held much converse with intelligent women. There she became a nun, Sor [Sister] Juana Inés de la Cruz. Her apartment served as a salon where she received men and women for intellectual discussion. She acquired a large personal library and studied hermeneutics (scriptural interpretation), history, logic, mathematics, music, natural philosophy, poetry, rhetoric, and theology. Most of her output was poetic—she said she did violence to herself not to write in verse. Stephanie Merrim calls her “the last great writer of the Hispanic Baroque and the first great exemplar of colonial Mexican culture.”

Although she addressed many lines to Mary, other poems exalted Christ. For instance, here is the first stanza of “Hymn for the Feast of the Incarnation:”

Divine Love this day

became incarnate,

a gift so precious as to give

all other gifts their worth.

Male contemporaries attacked her. She broke with her Jesuit confessor because he maligned her. Without her permission, Bishop Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz published a letter she wrote criticizing a sermon by António Vieira, a well-known Jesuit preacher of the previous generation. This drew establishment wrath upon her. In response, she wrote a famed defense of female scholarship. In the end she was forced to give up literary pursuits and sold her library and scientific instruments to help the poor.

During a severe epidemic shortly afterward, Juana contracted the disease while nursing sick nuns. Juana Inés de la Cruz died on this day, 17 April 1695, about forty-five years old. Nicknames for her included “Mexican Phoenix,” “The Tenth Muse,” and “The Nun of Mexico.” Her portrait was painted by contemporaries and by posthumous admirers, including Miguel Cabrera. Mexico has honored her on its 200-peso bill.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

Sor Juana was part of the community that made up Christian History #130, Latin American Christianity: Colorful, complex, conflicted