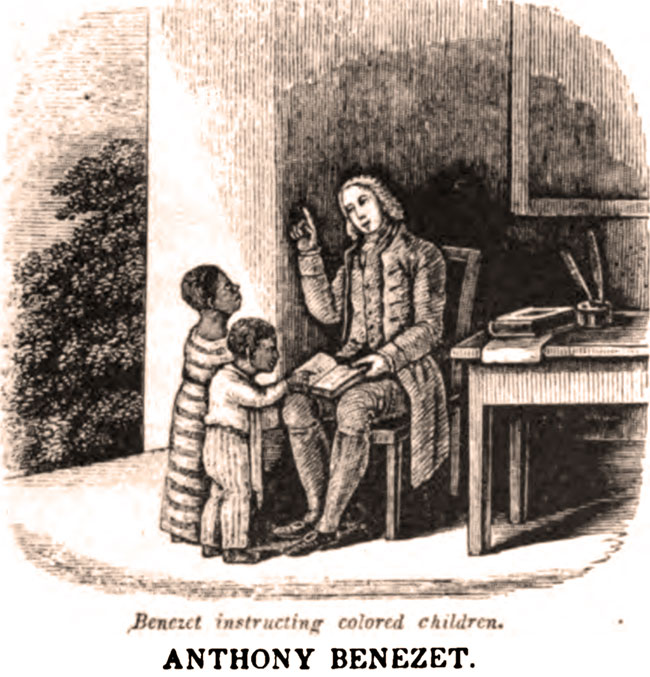

QUAKER ANTHONY BENEZET TAUGHT SLAVES AND CHAMPIONED GOOD CAUSES

[Above: This 18th-c woodcut is the only known portrait of Benezet. Adapted from the frontpiece in George S. Brookes, Friend Anthony Benezet. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1937.]

THE BENEZET FAMILY escaped religious persecution in France, settled for a while in England, and then migrated to America. After trying his hand at various occupations without success, Anthony Benezet found his calling as a school teacher in Philadelphia. He also joined the Quakers, convinced that their practices were closest to what Jesus had taught.

With his heart set on loving God and neighbor, Benezet became known for his efforts to help humankind. He was at the forefront of many worthy causes. Before the temperance movement, he wrote a tract against the abuse of alcohol and encouraged Quakers to neither make nor sell spirits. At a time when American Indians were regarded with hostility, he took up the cause of their well-being. As an educator, he introduced kindly methods in place of the harsh tactics that generally prevailed. He opened one of the first all-girls’ schools in the thirteen colonies, and educated a deaf and dumb girl at a time when those born without hearing were generally neglected or thought to be under a curse. He also wrote letters advocating peace among nations.

Above all, he was at the forefront of the fight to abolish slavery. He reprinted some writings of Granville Sharpe, who had won a judgment that any slave who set foot on English soil immediately became free. Meanwhile Sharpe had reprinted writings of Benezet. Neither knew what the other had done until afterward, but their shared interests made them fast friends, communicating by the snail-mail of the day: sailing ships on the Atlantic. Through Sharpe and Benezet, Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce became champions of emancipation.

To the archbishop of Canterbury, Benezet addressed one of his most famous letters, pleading that the English primate exert his influence in Parliament to end the slave trade:

I herewith send thee some small treatises lately published here on that subject, wherein are truely set forth the great inhumanity and wickedness which this trade gives life to, whereby hundreds of thousands of our fellow creatures, equally with us the objects of Christ’s redeeming grace, and as free as we are by nature, are kept under the worst oppression, and many of them yearly brought to a miserable and untimely end.

Benezet urged Quakers to free their slaves (which many did), and appealed for emancipation throughout the colonies. Eventually Quakers barred slaveholding members from taking part in Quaker business. Among his efforts in behalf of slaves was an eye-opening account of the vicious Guinea slave trade. In 1775 Benezet would take the lead in forming the first abolitionist society in North America.

Meanwhile, he was deeply concerned that “negroes,” as he called African Americans, be provided with an education. In 1750, he began teaching an evening class for African Americans, both free and slave. His experiences led him to assert that blacks “possessed intellectual powers by no means inferior to any other portion of mankind.” In January 1770, Philadelphia’s Quakers, probably at his instigation, discussed funding a school for African Americans. Through letters and personal appeals, he raised funds for the project. On this day, 28 June 1770, Benezet witnessed the opening of the school, with twenty-two children enrolled. They learned reading, writing, and arithmetic, and received moral instruction.

So dear was this project to his heart that in 1782, when he was sixty-nine and the school without a teacher, he resigned his girls’ school to teach the African Americans. Two years later he died. His will made provision for a godly replacement, urging “that in the choice of such tutor, special care may be had to prefer an industrious, careful person, of true piety. . . .”

His death occasioned a turnout larger than any other funeral up to then in Philadelphia. Among the many who poured out to honor his memory were hundreds of black people, eager to show their appreciation for the efforts he had expended in their behalf.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more on Quakers watch the video Quakers: That of God in Everyone at Redeem TV

Quakers can be purchased at Vision Video.

and read Christian History #117 The surprising Quakers