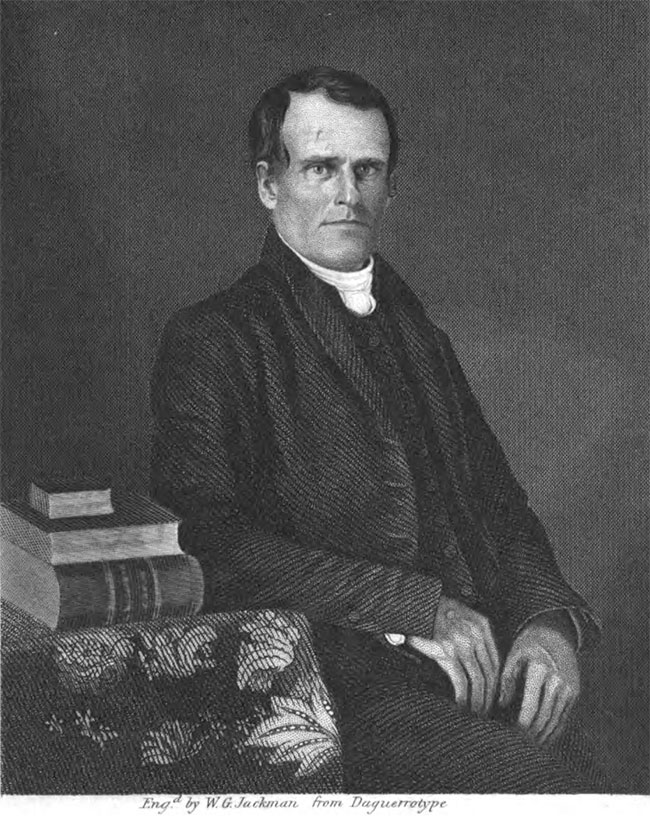

ORANGE SCOTT GOT IN TROUBLE FOR FIGHTING SLAVERY

[Orange Scott. Engraved by W.G. Jackman. Scott, Orange, and Matlack, Lucius C.. The Life of Rev. Orange Scott: Compiled from His Personal Narrative, Correspondence, and Other Authentic Sources of Information. In Two Parts. United States, C. Prindle and L. C. Matlack, 1847. Public domain.]

HISTORY SHOWS that when brave souls dare to rock the boat by exposing wrongdoing in the church, they are usually the ones called troublemakers rather than the actual wrongdoers. That was the experience of Orange Scott and his associates in the Methodist Episcopal Church. When they spoke against slave-owning, their church tried to silence them.

Early on, American Methodists had taken a strong stand against slavery. However, many southern Methodists owned slaves. Even some pastors held humans in bondage. In order to maintain the union of northern and southern churches, northern Methodists largely swept the issue out of sight, or called for gradual emancipation.

Orange Scott became a Christian in 1820 when he was twenty-one years old. Within six months he was preaching throughout New England. Revivals followed wherever he went. Largely self-taught, he gathered knowledge by reading and attending lectures. Not until 1833 did he encounter serious arguments against slavery. Within months he was denouncing it as a great evil; and he encouraged others to demand immediate abolition. Warned that his vocal opposition would make enemies and harm his prospects for advancement, he replied, “What I do is from a sense of duty. If the declaration and defense of anti-slavery sentiments make me unpopular, then I am willing to be unpopular. My course is onward.”

In sermons and lectures, he entreated his listeners to respect the image of God in the enslaved. He urged them not to do to others what they would not like done to themselves. He reminded them that the Bible commands us to give our servants what is fair. And because God calls himself the God of the oppressed, it is not wise to be an oppressor. God does not play favorites.

For the next nine years, Methodists from the south and bishops from New England joined to attack him relentlessly. They slandered him and stripped him of his position of leadership. Every effort Scott and his allies made to effect change was either voted down or killed with procedural motions.

Finally, in 1842, joined by LaRoy Sunderland and Jotham Horton, he left the Methodists. Soon others joined him. On this day, 31 May 1843, Orange Scott presided over a convention at Utica, New York, to establish the Wesleyan Methodist Connection. Representatives from ten regions of the United States attended. The new church was antislavery and structured without bishops and superintendents.

Scott published the Connection’s journal and managed its book supply. Already suffering from tuberculosis, he struggled on with the work for four years, dying in 1847 at the young age of forty-seven.

His associate Luther C. Matlack wrote, “He identified himself with [the antislavery] cause at a time when to do so involved the loss of reputation, property, influence, and sometimes of life itself—when abolitionists were everywhere denounced as incendiaries and fanatics, and proscribed alike in the social circle, in the church, and in the State.”

Wesleyan Methodist churches proliferated. Scott saw the group’s numbers multiply before his death, and it continues to thrive to this day, with over a million members in one hundred countries. The Orange Movement to end all human trafficking worldwide took its name from Scott.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

The need for abolitionists is as strong today as ever. Learn what modern abolitionists are doing with Not for Sale: Parts 1 and 2 Watch at RedeemTV.

Not for Sale: the Global Problem of Human Trafficking can be purchased at Vision Video.