LATIN AMERICANS BREWED NEW THEOLOGY IN MEDELLÍN

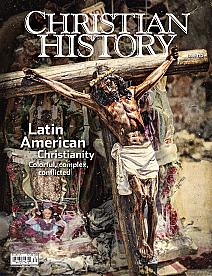

[Above: Catedral de Medellin-Fachada—Jorge Mario G. Mazo / [CC-BY-SA-2.0] Wikimedia.]

THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL, whose sessions ran 1962 through 1965, issued changes that the council hoped would allow the Roman Catholic Church to function more effectively and with greater popular appeal. Three years after it ended, Latin American bishops met in Medellín, Columbia, to discuss the impact of Vatican II and implementation of those changes in their region.

However, the bishops went beyond mere implementation of Vatican II reforms. So refreshing was their dialog that some spoke of the conference as a “New Pentecost.” Latin America had long suffered from lack of spiritual education, a plethora of dictatorships, widespread ethnic discrimination, and endemic poverty with enormous income gaps between haves and have-nots.

The bishops took a hard look at these societal problems. On this day, 6 September 1968, the Conference of Latin American Bishops (called CELAM, the initials of its Spanish name) issued the document “Justice,” calling for systemic changes in politics, economics, educational institutions, family units, worker organizations, and other social entities to bring them into a more humane arrangement under Christian idealism:

Love, “the fundamental law of human perfection, and therefore of the transformation of the world,”* is not only the greatest commandment of the Lord; it is also the dynamism which ought to motivate Christians to realize justice in the world, having truth as a foundation and liberty as their sign. [*Vatican Council II, Constitution on the Church in the Modern World]

The general idea of uplifting the poor through application of Christian ideas and economic justice became known as “liberation theology.” Among the important results was widespread formation of CEBs, Christian Base Communities (Comunidades Eclesiales de Base). These small groups brought a measure of self-determination into parishes: not only did they meet for Bible study, but they usually elected their own leaders and decided on group goals and activities.

Often, however, the implementation and development of the Medellín call took on a Marxist tone, elevating economic change over spiritual change. Like the Social Gospel in the United States, Liberation Theology looked for salvation principally through economic and political action, often calling for redistribution of wealth. To the more radical clergy, Latin Americans in poverty were seen as an underclass—the oppressed. Victims of outside forces, they were not responsible for their own spiritual and economic condition. Theologians with this viewpoint advocated Christianized socialist mechanisms to make a better life here and now. Some called for violence to change the system and opposed traditional Western concepts such as free enterprise and private property. Institutional sin was described as violence, and as such was to be met with violence.

Under Pope John Paul II, the Vatican denounced aspects of Liberation Theology through its spokesman, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI). Pointing out the unsavory history of socialist regimes, the Congregation of Doctrine said, “Those who, perhaps inadvertently, make themselves accomplices of similar enslavements betray the very poor they mean to help.”

—Dan Graves.

----- ----- -----

Read more about Medellín and liberation theology in “A new Pentecost” in Christian History #130, Latin American Christianity