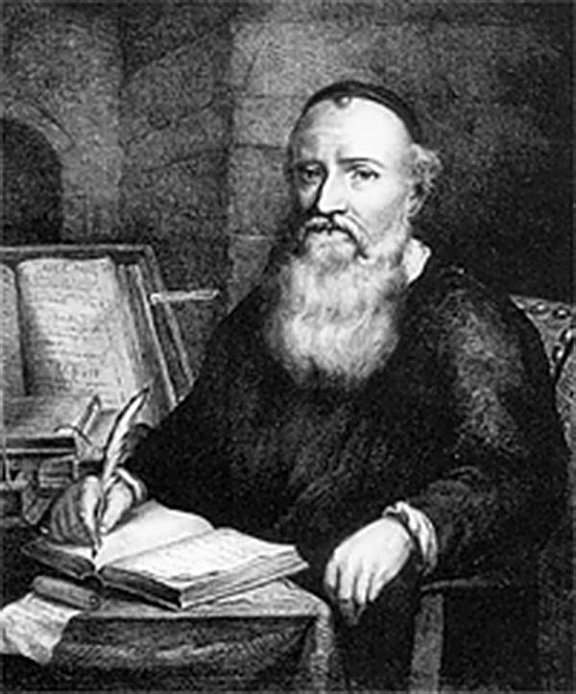

Godly Menno Simons Defended Anabaptist Theology in a Public Debate

Menno Simons became the pacifist leader of an Anabaptist reform movement.

IN A TOUCHING AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH, Menno Simons described his Christian pilgrimage from Catholic priest to pacifist Anabaptist in the Netherlands. He wrote that he did not open a New Testament until he had been a priest for two years: he was afraid it would mislead him. However, he was troubled by doubt whether the bread and wine of Eucharist actually turned into Christ’s body. He confessed this “sinful” concern but found no peace. Finally he decided to see what the Scriptures said. To his relief, he wrote, the Bible convinced him no such doctrine was taught. But now he became uneasy at the practice of infant baptism which he could not find in the Bible, either.

He began to study the Scripture and the writings of Protestant reformers in earnest and even gained a name as an evangelical preacher within the Catholic church. Meanwhile, he continued to live at ease, playing cards daily and teaching only those truths that would not get him into trouble with his church. “I wished only to live comfortably and without the cross of Christ,” he admitted. What forced him into a deeper commitment was the failed Anabaptist revolution in the city of Münster. Many people surrendered everything they owned to follow the rebel cult—and died for it.

Simons realized that if he had preached the truth he had come to believe, some of those people might have escaped the massacre. Now he committed himself to preaching the truth publicly. Soon he left the Catholic church and became pastor to a small group of Anabaptists. He married. The imperial government placed a price on his head. His life was one of continual flight, never able to stay long in one place.

Simons rejected any hint of the militant Anabaptist teachings that had led to Münster. He developed a theology focused on the New Testament and on following the teaching and example of Jesus, with emphasis on holy living as the true indicator of conversion. He gained many followers as he moved about northern Germany and the Netherlands. However, he was known to have been sympathetic to views on the Incarnation held by Melchior Hoffman, one of the leaders at Münster, and other reformers made false accusations against him and his teaching.

A case in point occurred in East Friesland. Countess Anna of Oldenburg was a mild ruler. She brought in the Reformed pastor and theologian John Lasco who was more tolerant regarding the execution of Anabaptists than many reformers. He was to head the state church and to investigate religious groups to determine which were heretical. Lasco invited Simons to a debate. .

The discussion opened in Emden on this day, 28 January 1544 with at least a small audience in attendance. Lasco and Simons discussed the incarnation, infant baptism, original sin, sanctification, and the true vocation of preachers. At the end Lasco asked for a written statement. Simons obliged. Lasco claimed Simons held views which the Anabaptist leader stoutly disavowed. Nonetheless, Countess Anna ordered him out of her territory.

Despite the price on his head and all that his enemies tried against him, Menno Simons lived to sixty-six and died a natural death. His ideas lived on. The Mennonites, named for him, became the largest Anabaptist group and a worldwide movement.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more on the Mennonites, read Christian History #84, Pilgrims & Exiles: Mennonites, Amish, and Brethren

The Radicals is the dramatic, true story of two Anabaptist leaders who died for their faith. Watch it at RedeemTV

The Radicals can be purchased at Vision Video.