FALSELY ACCUSED OF TREASON, OLIVER PLUNKETT FORFEITED HIS LIFE

[Above: Edward Luttrell (d. 1737), Oliver Plunket—National Portrait Gallery / public domain, Wikimedia File:Oliver Plunket by Edward Luttrell.jpg]

ON THIS DAY, 6 DECEMBER 1679, Irish authorities arrested Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh. Plunkett was hiding under the name Mr. Meleady. The alias was necessary, because the dominant English had ordered Roman Catholic church leaders to leave Ireland. Declaring that he was no “hireling shepherd,” to run away in face of danger, Plunkett had vowed to remain with his spiritual flock even if it meant death.

Plunkett was himself Irish. Born in County Meath in 1629, he was related to prominent Anglo-Irish families. As a youth he showed so much aptitude for study that benefactors sent the sixteen-year old to Rome in 1645 for additional education. English policy barred Catholics from many educational opportunities.

After a dangerous trip in which he was pursued by pirates and held hostage by bandits, he reached Rome. Plunkett trained for the priesthood, receiving ordination in 1654. He had promised to use his training in Ireland. However, the wars under Cromwell made a return to Ireland impractical and Plunkett obtained an exemption. He became a notable educator in Italy and represented Irish bishops in Rome.

His life took a new turn in 1669 when the exiled Archbishop of Armagh died. Pope Clement IX appointed Plunkett to the position. He was ordained quietly in Ghent so as not to affront the English. Pretending to be an Italian tourist, he reached London where he secretly met Queen Catherine (a Catholic). Leaving London, he acted the part of an army captain, singing tavern songs and kissing serving girls to uphold his disguise.

In Ireland, he threw himself into his duties. One of his first actions was to found a school to improve the training of priests. He also held many synods to correct lapses and settle disputes. He settled a dispute between Franciscans and Dominicans in favor of the Dominicans. This decision so outraged two Franciscans in Rome that they beheaded a statue of Plunkett. His enemies smeared him, forcing him to write long explanations to Rome.

Meanwhile, he went from county to county, offering the sacrament of confirmation to about fifty thousand people and urging cohabitating couples to marry. He negotiated peace between Irish rebels and the English-backed government. Warned that his health would suffer from overwork, he replied: “When a sailor has a fair wind he sets full sail.”

It was well that he worked so hard because in three years persecution broke out anew. To his dismay, anti-Catholics burned the school he had founded. For many months he had to hide before the situation eased and he was able to move about again.

The improved situation turned sour when a felon named Titus Oates alleged a Catholic plot to replace King Charles II with his Catholic brother James and to slaughter Protestants. Lord Shaftesbury pretended to believe this story that became known as the “Popish Plot.” As a result, Plunkett became a marked man and had to go into hiding.

After he was captured, an attempt to try him in Ireland failed because the witnesses against him were such scoundrels they dared not appear in court where they faced arrest. As soon as Shaftesbury realized that in Ireland even a Protestant jury would not find Plunkett guilty, he moved the trial to London. Despite coaching, the witnesses gave such contradictory testimony that the first attempt to bring an indictment against Plunkett failed. After more rehearsals, the witnesses finally gave testimony that persuaded a grand jury to bring an indictment. Plunkett was granted five weeks to assemble his own witnesses, but bad weather delayed his friends and Irish counties refused to provide necessary documents without direct orders from the crown. Witnesses requested safe conduct passes so they themselves would not be arrested in England as Catholic rebels. As a result, Plunkett stood alone at his trial, not even allowed defense counsel. A jury found him guilty in just fifteen minutes.

“Those who once beheaded my statue have now achieved the same object in the case of its prototype,” said Plunkett. He was executed for treason, but as Lord Chief Justice Pemberton said, his real crime was his religion. However, Plunkett met his end so peacefully and made such a convincing statement on the scaffold that the tide of persecution turned. Within days, Lord Shaftesbury was himself arrested. Thus Plunkett became the last of the Catholic martyrs in Britain.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

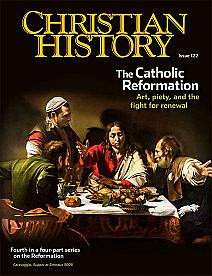

For more on Catholicism during the Reformation era, see Christian History #122, The Catholic Reformation