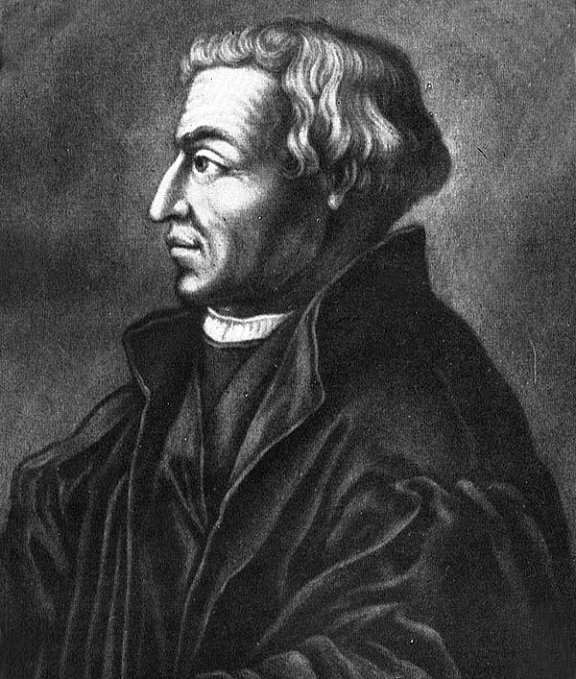

Bucer Ensured His Reforms Outlived Him by Founding Schools

Although a major reformer, Bucer is little known today.

MARTIN BUCER was born in Schlettstadt (Selestat), a city in Alsace, an area which has sometimes belonged to Germany and sometimes to France. Educated at its Latin school, he joined the order of the Dominicans in 1506 when he was about sixteen—he later claimed mainly in order to get a good education. On this day, 31 January 1517 he matriculated at the University of Heidelberg. There he studied the Bible and the works of Aquinas, Erasmus—and Luther. His studies led him to favor the evangelical cause.

When the Dominicans became suspicious of him, accusing him in Rome, Bucer asked for an annulment of his vows. He left the monastery and entered the service of the reform-minded nobleman Franz von Sickingen, who appointed him to a pastorate at Landstuhl where he married. When von Sickingen’s war against the Bishop of Trier failed, Bucer had to leave Landstuhl. He preached reform at Wissembourg in Alsace. The Catholic church excommunicated him and he fled to Strasbourg.

Bucer taught in Strasbourg’s schools and preached in its churches, wrote Bible commentaries and other works, and assisted in founding a system of Protestant schools. His Latin style was difficult to read, which perhaps explains why he is not as well remembered as other great reformers.

Bucer desired to bring divided Christians together. He believed that German Catholics and German Protestants should form a national church. However, political and military events prevented this ecumenical vision from becoming reality. He was not even able to unite Protestant factions. For example, he tried to bring Lutherans and Zwinglians together. These branches of the Reformation disagreed on the nature of the Lord’s Supper. Bucer’s own view was: “The Lord gives, in the sacrament, His real body and real blood, really to eat and to drink, for the nutriment of souls to eternal life.” Zwingli considered this definition too vague. Luther said scornfully, “It is better for you to have your enemies than to set up a fictitious fellowship.” Bucer and Luther did eventually reach an agreement on the Eucharist in 1536 (perhaps, in Luther’s case, mainly for political reasons).

After military defeat in the Schmalkaldic War, Strasbourg accepted a religious and political settlement with Emperor Charles V that forced Bucer to leave. In 1549 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer invited Bucer to become professor of theology at Cambridge. While in England, he wrote De regno Christi (The Kingdom of Christ) for King Edward VI. “It would seem fitting to write for Your Majesty a little about the fuller acceptance and reestablishment of the Kingdom of Christ in your realm,” he said. However, both men died before any of his suggestions could be implemented.

When the Catholic queen, Mary Tudor, ascended the throne of England, she considered Bucer’s ideas so dangerous that she had his bones dug up and burned. Even his tomb was destroyed.

Bucer never founded a church or established a religious system, but he influenced John Calvin, Oecolampadius, and many other reformers. Several religious groups viewed him as one of their own: Anglicans, Calvinists, Lutherans, and Puritans—a tribute to his ecumenical spirit.

—Dan Graves

------- ------ ------

"A motley, fiery crew" in Christian History #118, The People's Reformation, has more about Bucer