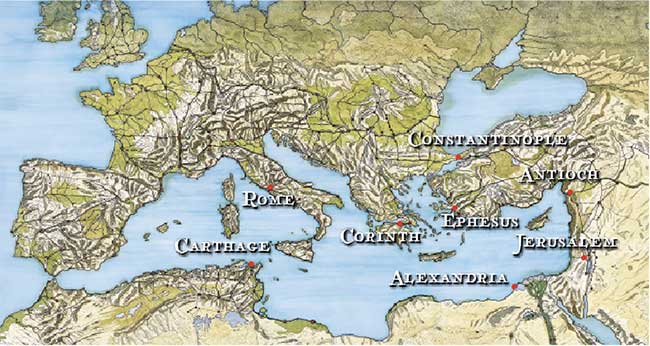

The Way spreads through the world

[General View of the Connections of the Roman Empire—Aquarelle de Jean-Claude Golvin. Musée départemental Arles Antique © Jean-Claude Golvin / Éditions Errance. ]

JERUSALEM

The very beginning of the Book of Acts confirms the presence and strength of the early church in Jerusalem—the first center of the church. After Jesus was taken up to heaven, the church in Jerusalem numbered 120 believers (Acts 1:15). Acts 2:5 declares that “there were staying in Jerusalem God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven,” and they were astounded when Galilean believers could speak their languages after receiving the Holy Spirit on Pentecost.

The earliest followers of Jesus in Jerusalem were Jewish; they continued keeping the Sabbath and going to worship at the Temple. In Acts 15 Paul and Barnabas returned to Jerusalem to discuss their ministry to the Gentiles with other church leaders. The leaders agreed that the Gentiles would not have to conform to most of the Mosaic law, including circumcision. James concluded, “It is my judgment, therefore, that we should not make it difficult for the Gentiles who are turning to God” (Acts 15:19).

James, who was the brother of Jesus, became the leader of the early church in Jerusalem. As Herod Agrippa ramped up his persecution of Christians, the Jewish high priest had James executed in c. 62. Shortly after, the Jerusalem church fled to Pella in modern-day Jordan.

The Roman authorities attempted to quash Jewish nationalism, leading to the First Jewish-Roman War, from 66 to 73. The Romans won, devastating the city of Jerusalem and destroying the Second Temple in 70. Of Jerusalem, Josephus wrote that it “was so thoroughly razed to the ground by those that demolished it to its foundations, that nothing was left that could ever persuade visitors that it had once been a place of habitation.”

ROME

Rome was the heart of the vast Roman Empire as well as its largest city. The church was founded in Rome prior to Paul’s ministry, and tradition holds that both Paul and Peter were martyred in Rome—Paul in c. 64 and Peter a short time later during Nero’s first persecution of Christians in c. 65.

Around the year 100, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people lived in Rome; the church, though still small, comprised perhaps little more than 7,000 Christians in the whole empire. Yet Roman authorities were wary of this new Christian movement, particularly its attraction not just to Jews but to pagans.

By the middle of the second century, Christians still met in Roman homes, but by the end of that century, around 7,000 Christians lived in Rome alone. Because early Christianity’s growth largely concentrated in urban settings, the church in Rome was comparatively strong, so much so that historians know it sent funds to Christians living elsewhere in the empire.

Rome’s dense population made for cramped living quarters within the city. Historian Jérôme Carcopino wrote that in Rome there existed “only one private house for every 26 blocks of apartments.” And though many more men than women lived in the Roman Empire—due to a high female mortality rate from female infanticide, childbirth, and abortion—when Paul wrote to the church in Rome in Romans 16, he greeted a fairly equal number of men and women. Women often came as the first converts to the Way.

By 313 the church in Rome and throughout the region had grown so large that the ruling government officially ceased persecutions against Christians. And Constantine—who ruled until 337—was the empire’s first Christian emperor.

ALEXANDRIA

Alexander the Great, king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia, founded Alexandria in 331 BC. A city on the Mediterranean coast (in modern-day Egypt), Alexandria was the second largest city in the Roman Empire after Rome. Christianity arrived in Alexandria later than it did in other cities in the Roman world, but when the gospel appeared, it spread rapidly. In the year 239, a negligible number of Christians lived in the city. (In the rest of the Greco-Roman world, the Christian population was about 1.4 percent.) But within 70-some years, 18 percent of the Alexandrian population was Christian (comparable to the rest of the empire).

Two disastrous epidemics, possibly measles or smallpox, inundated the Greco-Roman world in 165 and 250. Dionysius, the bishop of Alexandria, wrote an Easter letter to believers during the second epidemic. In it we see their bravery during the turmoil: “Most of our brother Christians showed unbounded love and loyalty, never sparing themselves and thinking only of one another. Heedless of danger they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ.”

Though Dionysius was surely biased toward his flock’s selfless provision for those ravaged by illness, pagan sources agree that the Christian population cared for the sick (for more, see CH #101). Pagan priests of the day failed to deliver to locals any meaning or hope in the misery, and they, along with the wealthy and powerful, often fled the cities.

Hellenistic natural law had no answers for such pain and suffering. Cicero had tried to explain sorrow in the century before Christ: “It depends on fortune or (as we should say) ‘conditions’ whether we are to experience prosperity or adversity. Certain events are, indeed, due to natural causes beyond human control.” Many suffering people, however, found such explanations lacking, and some turned to Christianity for both answers and hope.

Most scholars agree that the Septuagint (the earliest Greek translation of the Old Testament) was translated in Alexandria in the third century BC. In addition Apollos from Acts 18 was a Jewish native of Alexandria who preached in both Ephesus and Corinth. He was “a learned man, with a thorough knowledge of the Scriptures. . . . He spoke with great fervor and taught about Jesus accurately” (Acts 18:24–25).

ANTIOCH

Located in modern-day Syria and founded as a fortress in 300 BC by Seleucus I, successor of Alexander the Great, Antioch started out as home to both Syrians and Greeks. The Roman Empire seized the city in 64 BC, and eventually 18 different ethnic enclaves existed within the city, including a Jewish neighborhood. This made the city ripe for the conversion of both Jews and Gentiles.

Many scholars believe that Matthew’s Gospel was written in Antioch, then one of the largest cities in the Roman Empire. By the end of the first century, Antioch was a city of over 150,000 inhabitants. As a walled city, it was probably more densely crowded than even Rome. Despite the population, Antioch’s main thoroughfare, which the Greco-Roman world lauded, was only 30 feet wide.

Antioch had a difficult history of disasters and tragedies. Over 600 years of sporadic Roman rule, enemy forces overcame the city 11 times and largely burned it four times during the attacks. Antioch also endured hundreds of substantial earthquakes, three epidemics in which 25 percent of the population perished, and five major famines. On average Antioch endured one calamity every 15 years, and the city was only ever rebuilt because of its strategic position against the Persian border.

The book of Acts features Antioch prominently, as it was home to many Jews of the diaspora, some of whom became followers of Jesus. In Acts 6:5 Nicolas of Antioch, a convert to Judaism and then to Christianity, was selected as one of seven Hellenist leaders to be a deacon in Jerusalem. Barnabas also traveled to Antioch, later bringing Paul to teach those hungry for the gospel. As reported by Luke in Acts 11:26, “The disciples were called Christians first at Antioch.”

In the latter half of the third century, 10 churches assembled in Antioch. The city was considered one of the five original patriarchates—along with Constantinople, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Rome—recognized by the Council of Ephesus in 431.

CARTHAGE

Carthage, a city in modern-day Tunisia in North Africa, began as a Phoenician settlement and eventually ended up in Roman hands. After generations of destructive wars, Julius Caesar rebuilt Carthage in the middle of the first century before Christ. By the end of the first century after Jesus’s birth, it was a major Roman port on the Mediterranean. Carthage is only 160 miles across the sea from the island of Sicily near southern Italy.

Tertullian (c. 155–220) was a famous and devout Carthaginian whom many theologians refer to as the father of Western theology. Scholars credit this Christian apologist and defender against heresies as one of the first authors to refer to the Trinity in his Latin theological writings. An adult convert to Christianity, he asserted that “Christians are made, not born” in his seminal book, Apologeticus.

Cyprian (c. 210–258), a third-century bishop of Carthage, wrote in 251 about Christian hope during the second large epidemic that swept through the empire. Born into a pagan family and baptized as a Christian in his thirties, Cyprian knew firsthand pagan thought and Hellenistic philosophy. He argued that although pagans had no answer for the epidemic or hope for the future, for Christians, sufferings “are trying exercises for us, not deaths; they give to the mind the glory of fortitude; by contempt of death they prepare for the crown.”

Though not mentioned specifically in the Bible, Carthage as a city held an important place in the history of both the Scriptures and the early church. Numerous church councils were held in Carthage in the third to fifth centuries; there church fathers determined the biblical canon as well as laid important theological groundwork to prevent heresies from spreading throughout the Roman world.

CORINTH

This ancient city in Greece dates back thousands of years before the birth of Jesus. Trading hands between whichever empire was powerful at the time, Corinth fell to Roman forces in the second century BC. Julius Caesar resurrected the city in 44 BC, and it became home to thousands of Romans, Greeks, and Jews.

The apostle Paul first traveled to Corinth in the middle of the first century. While there he met Aquila and his wife, Priscilla, who had both moved to Corinth to avoid Claudius’s expulsion of the Jews from Rome. Paul and his new friends worked as tent makers, and each Sabbath Paul preached in the synagogue about Jesus and his gospel. After getting nowhere with his Jewish colleagues in Corinth, Paul vowed, “From now on I will go to the Gentiles” (Acts 18:6). He remained in Corinth for a year and half, preaching and teaching.

Even after Paul left Corinth, he ministered to its church. He wrote at least two letters to the Corinthians—the first while in Ephesus, the second while in Macedonia—exhorting them to keep their faith amid a pagan world.

Corinthian Christians were surrounded by Jews who vehemently rejected Jesus as well as pagans who worshiped a bevy of both Greek and Roman gods and goddesses. But Paul urged them to remain faithful: “Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified . . . but to those whom God has called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Cor. 1:22–24).

The more eastern and the less western a city was (save for the city of Rome), the faster the gospel seemed to travel. In Corinth, a city of 100,000 people in the year 100, the church was multiplying, particularly among women, a trend throughout the whole Greco-Roman world. Christian women typically married later—unlike pagan girls who were often married before puberty—and their husbands could not divorce them without cause (see pp. 17–20). Christians looked different from their pagan neighbors, because followers of the Way generally shunned divorce, infidelity, polygamy, and infanticide (particularly of female babies), all of which were rampant and widely accepted within Greco-Roman society.

EPHESUS

Ephesus is located on the western coast of modern-day Turkey, just 50 miles south of ancient Smyrna. Once located on the Aegean Sea, the city ruins now sit some two miles from the shoreline. Often in the hands of various rulers, Ephesus came under Roman rule in 129 BC, which lasted until the third century. During Jesus’s lifetime, Ephesus greatly prospered and became a center of trade and culture. Its estimated population in 100 was 200,000.

Ephesus boasted the famous Temple of Artemis (one of the seven wonders of the ancient world), the grand Library of Celsus—2,000 square feet in size and holding some 12,000 scrolls—and a large amphitheater. This multicultural city was home to Greeks, Romans, and Jews.

Paul first traveled to Ephesus in 52 following his time in Corinth. Similar to his Corinthian trip, Paul started by preaching to the Jews in the Ephesian synagogue but quickly moved his daily discussions to the school of Tyrannus. In Acts 19:10 Luke declared that these lectures “went on for two years, so that all the Jews and Greeks who lived in the province of Asia heard the word of the Lord.”

Though many Ephesians were open to Paul’s preaching, some even converting to the Way, the book of Acts gives us a glimpse into one group that was unhappy with his ministry. Demetrius, a silversmith who crafted shrines of Artemis, gathered his fellow craftsmen to remind them that they derived their livelihoods from honoring the goddess, and he led them to the grand theater in rage and protest (Acts 19). Though the mob was eventually quelled, Luke described Ephesus as a diverse city wrestling with and threatened by this new Christian faith.

CONSTANTINOPLE

Located in modern-day Turkey where Asia meets Europe, Constantinople (now Istanbul) was founded under that name by Emperor Constantine in 324. Its previous name was Byzantium, and the area had been inhabited since perhaps as early as the thirteenth century BC.

Emperor Constantine consolidated the Roman world and became leader of the entire empire after he defeated Emperor Licinius. He declared Constantinople the new center of the Roman Empire, rejecting Rome because of political and cultural conflicts; this greatly diminished the power of the Roman pagan elite. It was time to start anew, and his Nova Roma was consecrated on May 11, 330. From this place he hoped to restore the empire’s glory, in part through the elevation of Christianity.

The city of Constantinople needed Roman refurbishment, so Constantine had columns, art, statues, and other ornaments carried from various cities around the empire to decorate the new capital. Some 50 years later, church father Jerome would say that “in clothing Constantinople, the rest of the world was left naked.” In addition to accumulating ornamentation, Constantine gave privileges to new residents of the city to increase the population: exemptions from taxes and serving in the military, and free goods (wheat, oil, and wine).

In the earlier church, most Christians had worshiped in private residences, later in cemeteries (such as the Roman catacombs), and even later in some designated church buildings. The oldest church, located in modern-day Syria, is dated to around 250. After Constantine’s conversion in 312, however, Christian worship began to change. In Constantinople Christian worship utilized some ornamentation and practices from the pagan world, such as the use of incense, as well as ornate clothing for priests, processionals, and choirs.

Constantinople was the cultural and educational center of the Mediterranean region for 1,000 years until the Ottoman Turks conquered it on May 29, 1453. CH

By Jennifer A. Boardman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #147 in 2023]

Jennifer A. Boardman is a freelance writer and editor. She holds a master of theological studies from Bethel Seminary with a concentration in Christian history.Next articles

Questions for reflection: Everyday life in the early church

Reflect on life among the earliest followers of Christ

the editorsRecommended resources: Everyday life in the early church

Read more about everyday faith in the early church in these resources recommended by our authors and THE CH TEAM.

the authors and editorsDid you know? Lilias Trotter

Lilias Trotter’s life intersected many trends in Victorian art, culture, mission, and service work

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate