“The road to the future runs through the past”

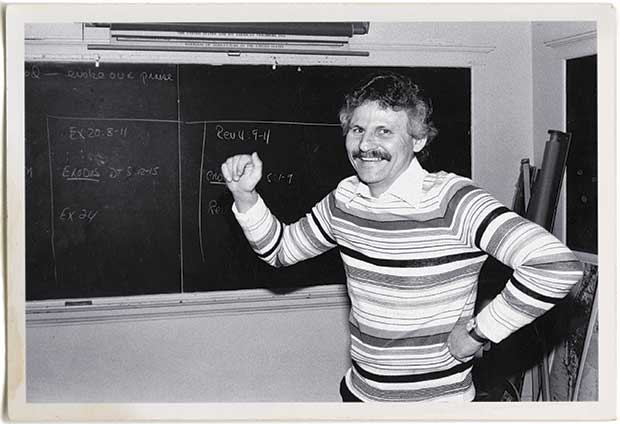

[Bob Webber at Weaton—Courtesy of Archives, Buswell Library, Wheaton College (IL)]

How do you deliver an authentic faith into the new cultural situation of the twenty-first century? . . . The way into the future, I argue, is not innovation or a new start for the church. Rather, the road to the future runs through the past.

So wrote Robert Eugene “Bob” Webber in his book Ancient-Future Evangelism (2003). And perhaps few evangelical figures have been more closely identified with recent retrieval of the ancient Christian past than Webber. He taught, spoke, and published prodigiously on the recovery of the ancient Christian tradition by present-day evangelicals. Both followers and critics acknowledge him as a catalyst in the awakening of American evangelicals to their ancient Christian heritage.

From the Congo to Wheaton

Bob Webber was a “missionary kid,” born in the Congo and raised in Western Pennsylvania. The son of a Baptist minister, he went to Bob Jones University before attending Anglican, Reformed, and Lutheran institutions: Reformed Episcopal Seminary, Covenant Theological Seminary, and Concordia Theological Seminary. Many of the seeds of his turning back to the past

were sown in the course of his diverse training.

On completion of his ThD at Concordia in 1968, Webber was hired by flagship evangelical school Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, where he served as professor of theology until his retirement in 2000. In retirement he served as a professor of ministry at Northern Seminary in the Chicago suburbs until his death from pancreatic cancer.

Webber’s early theological interests focused on evangelical apologetics and engagement with culture. He was concerned about the challenge of secular humanism, the belief that humans do not need God to be moral and live a fulfilling life. However he came to a crisis point early in his career that would transform his approach and set him on a new path in his life, thought, and ministry.

In the fall of 1969, Wheaton College invited the young professor of theology to preach a sermon during the chapel service. He determined to speak on an evangelical response to modern secular culture. However as he pondered a response to the existential despair pervading the late 1960s, he realized that his rationalist training could not provide an answer. A despairing culture did not need arguments for God’s existence; it needed an encounter with the living God.

Webber soon became convinced that Christian worship was the primary context for encounter with God, and this led to a twofold discovery. The first was liturgical worship. Frustrated with the “educational” approach of the sermon-oriented worship he had experienced at Wheaton and elsewhere, Webber attended a Roman Catholic Easter Vigil in the spring of 1972. As he participated in that liturgy, he encountered the reality of the Resurrection like never before.

This led in turn to a second discovery: the church fathers. Webber had been introduced to the church fathers in graduate school, but he now began earnestly reading them for what they had to say about worship. He found himself drawn to the Christ-centered liturgical practices of the ancient church.

An ordered experience of Christ

Webber soon made his way into the Episcopal Church. He found in the liturgical tradition of Anglican worship the same principles he had encountered in the early church. He also discovered that liturgy aided his evangelical commitments. In Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail (1985), which describes his journey, he wrote,

I am drawn to [Anglican worship] because it is so thoroughly evangelical. I have always confessed Christ as the central person of human history and of my life. Yet, until my worship life was oriented around an ordered experience of Christ not only on a weekly, but on a yearly pattern, I was unable to express in a concrete way my personal commitment to Christ.

Continued reading of the church fathers led to further transformation of his theology. In the sacramental practice of ancient Christianity, he discovered a way to reclaim the tangible means by which God mediates grace; in the spiritual practice of the ancient church, he found a model for more holistic spirituality; and in the ecclesiology of the ancient church, he uncovered an understanding of the church’s ecumenical unity. By the mid-1970s Webber had made the turn to what would become his “ancient-future” orientation.

A person of immense vitality, Webber published over 40 books and 175 articles in the course of his 40-year career—in addition to his full-time teaching and frequent speaking engagements. And he was a reformer for the people. He had little interest in writing for his academic peers. Rather he sought to inform and persuade a lay evangelical audience, with the goal of changing minds, hearts, and habits.

Webber was also an organizer. In 1977 he brought together a group of sympathetic theologians—including Donald Bloesch, Peter Gillquist, and Thomas Howard—to issue what they called “The Chicago Call: An Appeal to Evangelicals.” Under Webber’s direction 45 evangelical leaders drafted this statement at the National Conference of Evangelicals for Historic Christianity, held in Chicago in May of 1977. The call summoned evangelicals to recover their historic Christian roots and history, embrace creedal identity, practice sacramental integrity and authentic spirituality, and prize the authority and unity of the church.

The “Chicago Call” garnered little response at the time; however it crystallized an agenda that Webber subsequently followed. In 1978 he published a book that signaled this new agenda, Common Roots: A Call to Evangelical Maturity. David Neff, then editor of Christianity Today, remarked in an introduction to a later edition of the book:

In both the Chicago Call and Common Roots, Webber and his friends saw the potential in tradition for the renewal and reorientation of evangelicalism. This was not capital-T Tradition as some fixed authority, but a dynamic history of the Holy Spirit in the Church, leading and guiding it (as Jesus had promised) into all truth (John 16:13).

Retrieval for renewal

In this Webber differed from his colleagues Howard and Gillquist. Howard (b. 1935), author of Evangelical Is Not Enough (1984) and brother of missionary Elisabeth Howard Elliot, eventually became Roman Catholic; Gillquist (1938–2012) became an Orthodox priest. But for Webber the turn to the church fathers was not a return to the Christian past, but a retrieval of the Christian past for the renewal of the Christian present and future. While others chose “capital-T Tradition” by departing to Catholicism and Orthodoxy, Webber remained a self-identified evangelical—albeit an Anglican one—and continued in the course he had set.

In Common Roots Webber identified five key areas of retrieval for evangelicals that correspond broadly to his plan of renewal in the “Chicago Call”: church, worship, theology, mission, and spirituality. These became the focus of his work throughout the remainder of his career. But it was worship to which Webber would devote the lion’s share of his efforts beginning in the early 1980s.

Perhaps Webber’s most widely recognized book is the one that launched this agenda: Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail: Why Evangelicals Are Attracted to the Liturgical Church (1985). While Common Roots set his theological agenda, Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail tells Webber’s story. In doing so it became emblematic of a movement that would include several generations of evangelicals and continues today. Like Webber many who have taken the Canterbury Trail were first drawn to it through worship.

It is difficult to overstate Webber’s commitment to the renewal of evangelical worship. Between 1985 and 2007, he wrote eight separate books on worship, developed a seven-volume worship curriculum, edited an eight-volume Library of Christian Worship, produced six audiovisual worship resources, and wrote some 20 journal articles and over 100 popular articles—all in some way related to the ancient-future renewal of evangelical worship.

Along the way Webber traveled and spoke widely, hosted workshops, was one of the first evangelicals to be admitted to the North American Academy of Liturgy, and founded the Institute for Worship Studies based in Jacksonville, Florida, serving as its first president from 1998 until his death. It continues today.

Webber first coined the phrase “blended worship” as an attempt to describe his desired integration of traditional and contemporary elements in worship, later shifting to the term “convergent.” However he eventually settled on “ancient-future,” which described his approach more accurately while allowing him to address other topics, such as evangelism, formation, spirituality, church unity, and the continuing need for renewal.

Foremost among his other concerns was a desire to recover ancient Christian practices of catechesis. His Journey to Jesus curriculum (2001) and Ancient-Future Evangelism were both attempts to catalyze this renewal. In the 2000s Webber explored this broader emphasis through his Ancient-Future book series, which amplifies his original call: to renew the evangelical church by retrieving the wisdom of the ancient church.

That effort culminated in another public call in 2006, the “Call to an Ancient Evangelical Future” (see p. 20). A group of evangelical theologians drafted it under Webber’s leadership, and 500 evangelical leaders then signed it.

The new “Call” emphasizes the primacy of the biblical narrative and raises up the community of the church as the primary place commitment to the Bible is lived out. It asks evangelicals to turn away from “redefinitions of the church according to business models” and “lecture-oriented, music-driven, performance-centered, and program-controlled models” of worship.

After postmodernity, what?

What distinguished the Ancient-Future series, as well as the new “Call,” from Webber’s previous summonses to renewal was his growing recognition of the postmodern and increasingly post-Christian character of Western society. Webber saw emerging parallels between pre-Christian antiquity and post-Christian postmodernity. These convinced him all the more that the retrieval of ancient faith and practice was the best way to equip the evangelical church to survive—and thrive—in the twenty-first century.

To that end he established the Center for an Ancient Evangelical Future in 2006 at Northern Seminary, founded on the principles of the new “Call.“ Webber envisioned the center as an ongoing catalyst for retrieval and renewal, but he died not long after its founding. Reestablished in 2012 the center continues Webber’s work in the renewal of catechesis at Trinity School for Ministry in Pittsburgh, an evangelical seminary in Webber’s beloved Anglican tradition.

Through his writing and teaching, Webber was instrumental in in awakening American evangelicals to their ancient Christian heritage. Today one can witness the widespread use of ancient liturgical practices and growing interest in the renewal of catechesis by evangelicals and others across a remarkable spectrum of churches (see “A church of the ages?” pp. 46–49). An Internet search on “ancient-future church” will turn up many websites for churches that identify as such.

Webber’s ancient-future movement has proven especially attractive to younger evangelicals. While many remain in churches of the “free church” tradition, others continue to follow Webber on the road to Canterbury and Anglicanism. Wheaton College, Webber’s academic home for over three decades, had only a handful of Anglican students and two Anglican faculty—one of them Webber—when he wrote Canterbury Trail. Today dozens of Wheaton faculty and hundreds of students identify as Anglican. It is hard to imagine a more fitting tribute to Bob Webber’s life and work. C H

By Joel Scandrett

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #129 in 2019]

Joel Scandrett is assistant professor of historical theology and director of the Robert E. Webber Center at Trinity School for Ministry. He served as one of the editors of the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture series and is a priest in the Anglican Church of North America.Next articles

Living a “with-God” life

The friendship of Richard Foster and Dallas Willard and the birth of Renovaré

Tina FoxChristian History Timeline - Responses to Modernity

Attempts to recover the spirit of the first Christians are almost as old as Christianity itself, but we focus here on those that arose in some way as a response to problems of the modern world.

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate