Misunderstood missionaries

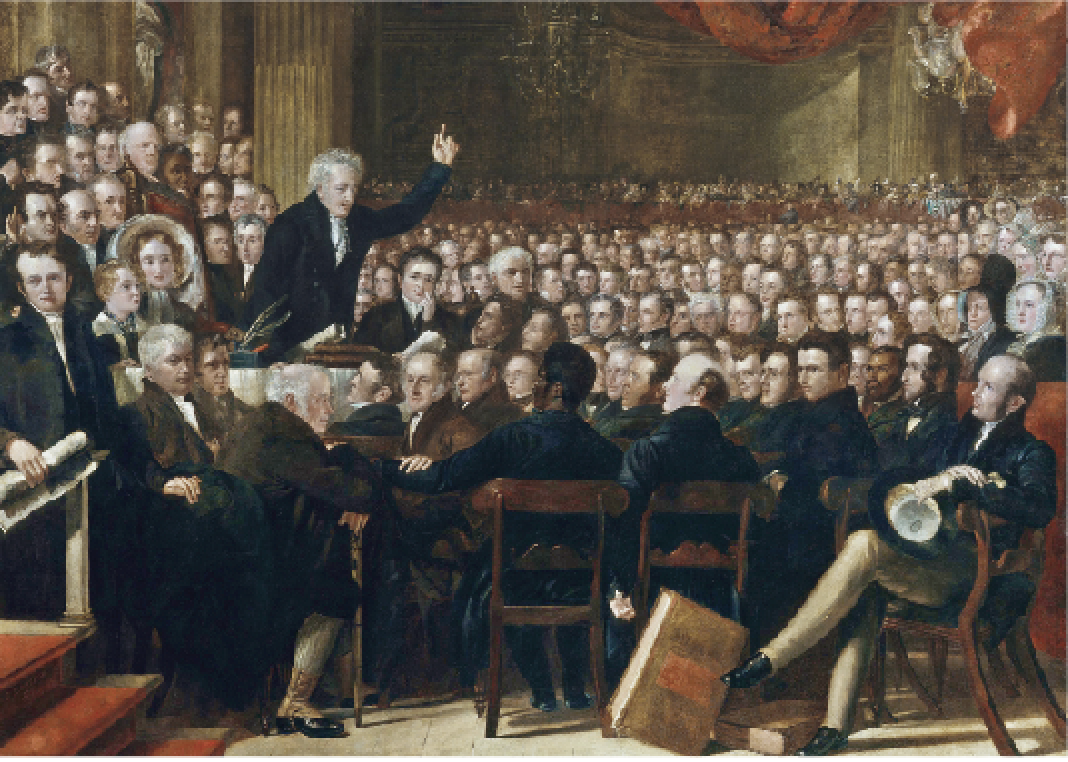

[Benjamin Haydon, The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840—National Portrait Gallery / [Public domain] Wikimedia]

The cartoon’s point is clear. Two members of a native South American tribe confront a missionary holding a large Bible and tell him: “I’ve got a better idea. Why don’t you come visit the temple tomorrow, and we’ll teach you how to live a life of sacrifice?”

Such a caricature of Western missionaries has taken hold recently—those whose religious zeal leads them to misunderstand local cultures, sometimes with tragic results. But a closer look reveals a far more complex picture of missionaries who fought colonial governments for more just treatment and less financial exploitation—and who sometimes won.

The bridge between

Nineteenth-century missionaries held a unique bridging position between the colonized they intended to reach and the colonizers whose culture they shared. Widely dispersed in the colonies, they directly witnessed colonizers abusing indigenous people. Such abuses hampered missionary work by turning locals against Westerners and against Christianity. But missionaries had power in the West through religious supporters and funders that they wrote to regularly and could mobilize. Prior to modern international human rights organizations and news organizations, missionaries and their supporters stood at the forefront in this fight.

Most missionaries were not against the idea of colonialism—it allowed them to enter many countries. But they wanted a moderate form. For example, prior to the First Opium War (1839–1842), missionaries had not openly resisted the British opium trade; to gain access to China, some worked as translators for opium trading companies. However, the Opium Wars changed two things. First, missionaries could now enter China without working for trading companies. Second, they saw the consequences of addiction; spurred to compassion they became the main group mobilizing Europeans and Americans against the opium trade.

Missionaries strove to evangelize the poor and marginalized as well as the wealthy and powerful, and soon found that the former responded more readily to the gospel. Missionaries got to know their needs and concerns. Some who had gone to the mission field with little social agenda became convinced that preaching was not enough.

Many missionaries had already come from social activist traditions. Protestant missions grew out of the Second Great Awakening—spiritual revivals that also gave birth to abolitionism, temperance, prison reform, and many other social movements. Before going abroad many early missionaries were already actively involved in these movements, as were the mission boards that sent them.

By the mid-nineteenth century, missionary organizations had budgets to rival those of large secular organizations. Harvard University’s endowment, for example, was less than a half million and its annual revenues were less than $50,000 in 1846. That same year the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions had annual revenues of over $250,000! The largest missions and Evangelical reform agencies outstripped all but a few commercial banks. Great Britain also had a massive missions sector.

With such vast resources, missionaries smuggled out photographs and reports about abuses, publicizing them with their own media empires—well ahead of the development of broad, secular, international news organizations. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, missionaries more than any other group wrote home and gave regular speeches about life in colonial territories. Politically they mobilized supporters to pressure government officials; in fact on several occasions this pressure forced the British colonial government to recall governors and magistrates.

Missionaries and their supporters also helped fashion the British economic concept of trusteeship—the idea that the colonial government had an obligation to develop colonial territories with an eye toward their ultimate independence. Edmund Burke, heavily influenced by his Quaker tutor, first proposed the concept in the 1770s, arguing for it based on divinely sanctioned natural law. Initially trusteeship had little currency outside missionary circles. But missionaries continually promoted it and tried to hold government policies to this standard. By the twentieth century, many Westerners shared the idea.

Not just ruling but redeeming

Missionaries’ economic and political influence particularly shaped the antislavery movement. In the eighteenth century, the British were the world’s leading slave traders—buying people from Africa to enslave, using them in their colonies, and selling them to others. Death rates on ships and plantations were high. The British set up monopoly trade relationships and used violence to extract resources and labor.

As missionaries spread throughout British colonial territory, they were exposed to the horrors of the slave trade and the decimation of indigenous peoples. Soon they used their power and wrote their supporters back in Great Britain about these abuses. Initially they tried to stay apolitical; they needed slave owners’ permission to work with the enslaved. But as missionaries gathered slaves for weekly religious services, trained some to lead congregations, and taught congregants how to read and write, that changed.

Pressure campaign

Literate enslaved people began to interpret the Bible for themselves and read newspaper accounts of debates over political rights. They met and discussed plans outside direct observation of their owners. When several British missionary church leaders in Jamaica from the Nonconformist movement (those not affiliated with the Church of England) were implicated in a slave uprising, slave owners burned down churches, put several missionaries in prison, and barred the enslaved from learning to read and meeting for worship. For the missionaries this was the final straw. The Baptist Magazine reported on an 1832 speech by missionary William Knibb:

[He said] the Society’s missionary stations could no longer exist in Jamaica without the entire and immediate abolition of slavery. He had been requested to be moderate but he could not restrain himself from speaking the truth. He could assure the meeting that slaves would never be allowed to worship God till slavery had been abolished.

A number of missionaries, some of whom had been imprisoned, tarred and feathered, or kicked out of British slave colonies, began touring Great Britain making fiery speeches and distributing petitions against slavery. Their supporters mobilized a massive pressure campaign calling for immediate abolition. Nonconformist dominance in the petition campaign so amazed the relevant parliamentary committee that they kept track of the religious traditions of petitioners: over 59 percent of Nonconformists and over 95 percent of Wesleyan Methodists signed petitions calling for the end of slavery. Allied with a small group of intellectual free-market economists, these British Evangelicals achieved the banning of slavery in 1834 and convinced the British Navy to suppress the slave trade conducted by other countries—against direct opposition of planters and Liverpool slave traders at a time when slavery was still highly profitable.

Spurred by their success with abolitionism and concerned by reports from missionaries in other colonies, Evangelical and Quaker missionary supporters established the Parliamentary Select Committee on Aboriginal Tribes in 1835. This group commissioned a worldwide investigation and collected well over a thousand printed pages of testimony about the consequences of colonization—much of it from missionaries.

White settlers’ abuses of indigenous peoples also shocked missionaries working in South Africa. In 1828 Dr. John Philip cataloged some of the abuses in his book Researches in South Africa and traveled in England to raise pressure for the government to stop them. Philip and his supporters were able to get ordinances passed that became the basis for a nonracial constitution for the Cape Colony, granting “all the natives of South Africa, the same freedom and protection as are enjoyed by other free people of the Colony whether English or Dutch.”

Later missionaries like John Mackenzie continued the struggle for equal legal protection for Whites and Blacks—Mackenzie even brought his ally Khama III to Britain and arranged publicity and a meeting with Queen Victoria. Although Anglo missionaries ultimately lost the struggle when Boer settlers took over the South African government in the twentieth century, they influenced colonial policy for almost a century and earned the ire of White settlers in the process.

Underhill meetings

Missionaries also restricted British colonial officials. In 1865 Edward Underhill, secretary of the Baptist Missionary Society, wrote a letter to the colonial secretary outlining the deteriorating economic situation for the formerly enslaved in Jamaica and describing abuses. He asked the colonial office for economic and political reforms including expanded suffrage. The colonial office forwarded the letter to Governor Eyre of Jamaica; Eyre responded angrily and began attacking Nonconformist missionaries. When the content of the letter became public, Blacks throughout the island held meetings to discuss it. These “Underhill Meetings,” named for the Baptist missionary, provided a platform for those who were angry with the government to air their grievances.

While tensions were high, a squabble over a court decision escalated into a riot at Morant Bay in which several White people were killed. Eyre sent in soldiers who killed several hundred Blacks, flogged hundreds more, and burned villages indiscriminately. He also ordered prominent mulatto leader George William Gordon court-martialed and hung without benefit of trial; Gordon had no direct link to the uprising.

The Colonial Office initially commended Eyre for his decisive action, but missionaries sent back damning reports, and their supporters mobilized a campaign that got Governor Eyre recalled and tried for murder. They argued the case in an attempt to set a precedent that English law would apply equally to Whites and non-Whites so that colonial officials would think twice before slaughtering civilians.

Missionaries sometimes lost fights, ignored abuses, or covered up abuses of their own. But overall they were a dominant social and economic force: ending the opium trade, restricting gun and liquor trade in Africa, fighting for native land rights, ending forms of forced labor, protesting abuses of civilians during the Boer Wars, and fighting for the rule of law in many colonies. Surveying achievements like these, the Committee on Missions and Government at the 1910 World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh wrote, “Like the Church at home, the Missions in the colonies are the conscience of the State.” CH

By Robert D. Woodberry

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #137 in 2020]

Robert D. Woodberry is director of the Project on Religion and Economic Change and senior research professor at Baylor University. This article is adapted from his dissertation.Next articles

Self-serving vice or society-building virtue?

The long-standing influence of Max Weber’s linking of Protestantism and capitalism

Kenneth J. BarnesChristian History timeline: Market matters

Some ways Christians have preached, thought about, shaped, critiqued, and participated in economic life throughout church history

The editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate