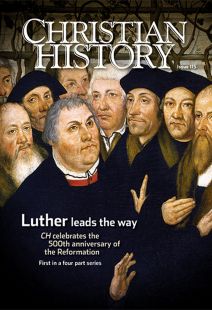

The man who painted the Reformation

MUCH OF WHAT WE KNOW about the physical appearance of Luther, his family, his friends, and other leaders of the German Reformation comes from the art of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553), German painter and master of woodcuts

Cranach, son of artist Hans Maler, was born in Kronach (modern-day Bavaria) and apprenticed to his own father as a youngster. Little else is known about his early life, but in 1502 he emerged in Vienna signing his work not “Lucas Maler” but “Lucas Cranach” after his hometown. In 1505 he became court painter to Frederick the Wise of Saxony. He moved to Wittenberg where he not only created paintings, woodcuts, and engravings for the court, but also supervised the general design of court festivities—essentially, a wedding planner for the sixteenth century.

In the early days of the Reformation, Cranach joined the Lutheran cause and became Luther’s friend. Cranach made at least five portraits of Luther; portraits of Luther’s parents, wife, and daughter Magdalena; portraits of Elector Frederick and his chaplain, Georg Spalatin; and views of the town and Castle Church of Wittenberg. He also illustrated the first edition of Luther’s German translation of the New Testament.

Cranach’s illustrations of the Book of Revelation were so impressive that one of Luther’s opponents borrowed them for his own translations of the New Testament. The ironic result was a Catholic version of the Scriptures with illustrations of Rome as the Babylon of the Apocalypse!

A banker as well as an artist, Cranach rose in Wittenberg society as much through his shrewd business sense as through his artistic talent; both were considerable. Though he loved Luther, Cranach worried that the man’s generosity could get him in financial trouble. He once refused to honor a financial promise Luther had made. Luther’s response: “At least you can’t accuse me of stinginess.”

Cranach lost his job as court painter when his boss, now Elector Johann Frederich, Frederick the Wise’s nephew, was defeated in battle and captured in 1547. Elector Johann was freed in 1552, and Cranach along with him, but he died soon after. His sons Hans and Lucas the Younger, as well as other disciples in his workshop, carried on his artistic memory and continued to produce artwork for the court.

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Paul Thigpen and the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

Paul Thigpen and the editors. A shorter version of this sidebar appeared in CH issue 34.Next articles

After the revolution

The beginning of the Reformation was not the end of Luther’s troubles

Mark U. Edwards Jr.What did Luther know and when did he know it?

When did Luther discover justification by faith?

Edwin Woodruff TaitLuther Led the Way, Did You Know?

Luther loved to play the lute, once went on strike from his congregation, and hated to collect the rent

the editors and othersThe man who yielded to no one

Erasmus “laid the egg that Luther hatched,” many said; why aren’t we celebrating his 500th anniversary?

David C. FinkSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate