The man who yielded to no one

IN 1508 Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) ran out of money while on a research trip in Italy. Already 40 years old (or 43: his date of birth remains disputed), priest and scholar Erasmus, the illegitimate son of a priest and a doctor’s daughter, was just beginning to emerge as a rising star in the learned circles of northern European humanists. Humanists were scholars who wanted to revive the literary heritage of ancient Greece and Rome.

Erasmus’s reputation was based on hard work. His Enchiridion of the Christian Soldier established his reputation as a spiritual and educational reformer. Enchiridion means “that which is held in the hand”—at once a “handbook” and a “dagger.” The title hints at the central thrust of Erasmus’s work as a reformer: renewed spiritual intensity among lay Christians, honed to a fine edge by a deeper engagement with Scripture and by wielding the dagger of prayer.

Erasmus had also published his own Latin translation of the New Testament, began a corrected version of its Greek text, and issued a collection of some 4,000 proverbs and maxims culled from ancient Greek and Latin literature. Erasmus’s laborious scrutiny of such ancient manuscripts made him a household name wherever classical literature was taught in Europe.

Being a household name did not, however, pay the bills in 1508. So Erasmus moved to northern Italy and accepted a job as tutor to 18-year-old Alexander Stewart and his younger brother, illegitimate sons of James IV of Scotland. By all accounts Erasmus and Alexander, installed by his father as archbishop of St. Andrews despite his young age, got on famously. Before his departure for Scotland in 1509, the archbishop gave his tutor a token of his affection: a signet ring bearing the image of Terminus, the ancient Roman god of bounds.

Erasmus adopted the god’s image and motto—Nulli concedo (“I yield to no one”)—as his own. It was a strange choice for a faithful Catholic priest whose earlier writings movingly commended imitating Christ’s simple humility. Indeed several of his friends thought it smacked of arrogance.

But Erasmus explained that the words were those of the god, not his own, and as such stood as a reminder of the inescapable bounds placed on human life by death—the final conqueror who really would yield to no one. He received a bitter reminder of this in 1513, when his protégé Alexander accompanied his father the king on an invasion of England, only to be cut down at Flodden Field.

The ruthless pope

That same year brought another death, though, which Erasmus greeted with glee. Julius II (pope from 1503 to 1513) was widely regarded as one of the most ruthless popes of his era. He focused his tremendous personal energy on making secure the defense of the Papal States (the territory on the Italian peninsula ruled directly by the pope), as well as recovering lands lost to rival powers Venice and France.

In 1506 Erasmus had witnessed the triumphal entry of Giuliano il terribile (“Julius the terrible”) into Bologna after a long and grueling siege of the city. “I could not help groaning within myself,” he wrote, “when I compared these triumphs, at which even lay princes would have blushed, with the majesty of the apostles, who converted the world by the majesty of their teaching.”

Not all contemporaries were so dismayed. In the year of Julius’s death, a little-known—at least at that time—Florentine politician named Niccolò Machiavelli wrote admiringly: “All these enterprises prospered with him, and so much the more to his credit, inasmuch as he did everything to strengthen the church and not any private person.” Machiavelli’s appreciation would echo through history in The Prince, a handbook for rulers on how to win power and get ahead in life.

Erasmus held a far dimmer view. Within a year of Julius’s death, an anonymous—and vicious—satire began circulating. Though Erasmus never owned up to having written Julius Excluded from Heaven, most modern critics see his fingerprints all over it. The dialogue is set outside the gates of heaven, where Julius and his genius (guardian angel) come face to face with the limits of papal power:

Julius: What the devil is this? The doors don’t open? Somebody must have changed the lock or broken it.

Genius: It seems more likely that you didn’t bring the proper key; for this door doesn’t open to the same key as a secret money-chest. . . .

Julius: I didn’t have any other key but this; I don’t see why we need a different one. . . .

Genius: I don’t either; but the fact is, we’re still on the outside.

St. Peter responds to Julius’s demands for admittance by reminding him that “this is a fortress to be captured with good deeds, not ugly words.” When Julius proudly describes a nearly exhaustive catalog of vices as his qualifications for entry, St. Peter responds with mounting horror:

Peter: Oh, madman! So far I have heard nothing but the words of a warlord, not a churchman but a worldling, not a mere worldling but a pagan, and a scoundrel lower than any pagan! You boast of having dissolved treaties, stirred up wars, and encouraged the slaughter of men. That is the power of Satan, not a pope. Anyone who becomes the vicar of Christ should try to follow as closely as possible the example provided by Christ. In him the ultimate power coincided with ultimate goodness; his wisdom was supreme, but of the utmost simplicity. … If the devil, that prince of darkness, wanted to send to earth a vicar of hell, whom would he choose but someone like you? In what way did you ever act like an apostolic person?

Julius: What could be more apostolic than strengthening the church of Christ?

Peter: But if the church is the flock of Christian believers held together by the spirit of Christ, then you seem to me to have subverted the church by inciting the entire world to bloody wars, while you yourself remained wicked, noisome, and unpunished. . . . Christ made us servants and himself the head, unless you think a second head is needed. But in what way has the church been strengthened?

Julius: …That hungry, impoverished church of yours is now adorned with a thousand impressive ornaments.

Peter: Such as? An earnest faith?

Julius: More of your jokes.

Peter: Holy doctrine?

Julius: Don’t play dumb.

Peter: Contempt for the things of the world?

Julius: Let me tell you: real ornaments are what I mean. …Regal palaces, spirited horses and fine mules, crowds of servants, well-trained troops, assiduous retainers—

Genius: —high-class whores and oily pimps—

Julius: —plenty of gold, purple, and so much money in taxes that there’s not a king in the world who wouldn’t appear base and poor if his wealth and state were compared with those of the Roman pontiff. …

The word picture of Julius in this exchange is a grotesque caricature, but the issues in dispute were real enough. They were the central planks in Erasmus’s reforming agenda: the importance of earnest faith and holy doctrine for the Christian life, along with contempt for the world and, above all, an imitation of the life of Christ. Against these Erasmus set the cynicism and political ambition of an institutional mentality. Julius had identified the church wholly with its exterior trappings—and ultimately, with himself—rather than with its true spiritual nature.

Erasmus did not take issue with church doctrine, but rather with the seductions of power, the beguiling distractions of materialism, and a forgetfulness of God’s eternal judgment that ought to keep all human aspirations within their proper limits. The whole comedy of the dialogue results from Julius’s incredulity, at first bemused and then enraged, at having found that the key of worldly power will not unlock the door of wisdom, the gateway to heaven.

Returning to the sources

Erasmus’s practical solution centered on a return to the sources of Christian faith and piety: the church fathers and, above all, the New Testament. During his life he produced editions of the writings of Basil of Caesarea, John Chrysostom, Irenaeus, Ambrose, Origen, Athanasius, Augustine, and Jerome, including biographical information and translations into Latin of those fathers who had written in Greek.

More controversially, he produced an edition of the Greek New Testament. In its second edition (1519), he added a fresh Latin translation and an explanation of how textual readings were arrived at, especially in difficult passages. Humanists and reform-minded scholars celebrated this Novum Testamentum Omne, though many found its amended readings unsettling. Erasmus’s friend Thomas Linacre, after first reading the New Testament in Greek, is reported to have remarked, “Either this is not the gospel, or we are not Christians.”

Erasmus took considerable heat from conservative theologians suspicious of the ways in which his Greek text undermined the language of the Vulgate, the Latin translation used in Catholic worship and as the basis for theological writings. Erasmus’s translation changed its wordings in some crucial places. But if the Western church had not erupted in a conflagration over the teachings of an obscure Augustinian friar in 1517, it is likely that little would have ever come of such complaints.

In the wake of Luther, critics charged that by tinkering with textual foundations, Erasmus was giving aid and comfort to a dangerous new theology that virtually scrapped the medieval church’s sacramental system. Take Matthew 4:17, rendered in the Vulgate as “From that time Jesus began to preach, and to say: ‘Do penance [paenitentiam agite], for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.’” Erasmus’s Greek, however, replaced “Do penance” with the single word, metanoiete—“Repent!”

Laying a theological egg

In 1518, writing to his friend and mentor Johannes Staupitz, Luther explained the impact of this altered reading on his own theological development before he wrote the 95 Theses:

It happened that I learned—thanks to the work and talent of the most learned men who teach us Greek and Hebrew with such great devotion—that the word poenitentia means metanoia in Greek. … While this thought was still agitating me, behold, suddenly around us the new war trumpets of indulgences and the bugles of pardon started to sound.

It is small wonder that “Erasmus laid the egg that Luther hatched” quickly became a common saying.

Erasmus himself was anything but pleased by these developments. Lampooning a bellicose and spendthrift pope like Julius after he was safely dead was one thing; uprooting, as Luther had done, a centuries-old set of devotional practices that formed the bedrock of Catholic piety was quite another. Erasmus saw himself as calling the church to return to the sources of its own most profound insights; Luther he regarded as a dangerous radical.

As battle lines hardened between Catholics and reformers in the years following the indulgence controversy, Erasmus faced mounting pressure from both sides to declare his loyalties. Despite his sympathies with many aspects of the new reform movement, and especially with the reformers’ scathing criticisms of the church’s corrupt practices, Luther’s gospel—and his personality—were too much for Erasmus to swallow.

Erasmus publicly broke with Luther in 1524 over the bondage of the human will, but neither Luther nor his conservative critics were content to leave him in peace. Erasmus spent the last 12 years of his life watching the study of classical and patristic literature he had labored so long to promote co-opted by increasingly militant Protestants or falling into disrepute among increasingly reactionary Catholics.

In a print made about a year before his death, Erasmus stands by a bust of that old god Terminus. Despite their lavish background, the two are flanked by a pair of scowling gods, arms folded, forbidding a return to the times of plenty. The expression on the face of Erasmus is one of thoughtful pensiveness, as though having reached the limit of—his wits? his intellectual powers? his life?—he now stands contemplating an unknown and uncertain future.

Terminus, by contrast, wears a mocking grin. Erasmus himself strove for reform, yet resisted the reformers. Caught between the forces of a divisive Protestantism and Catholic reaction, Erasmus never fully yielded to either side. His hopes for a renewal of Christendom through a return to the sources of Christian faith and piety were dashed against the rocks of confessional conflict. Death and schism triumphed in the end. CH

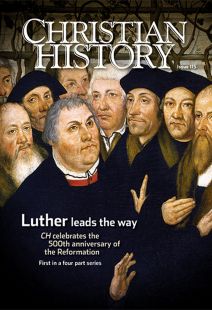

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By David C. Fink

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #115 in 2015]

David C. Fink is assistant professor of the history of Christianity and Christian theology at Furman University.Next articles

Preachers, popes, and princes

The men who mentored Luther, fought with him, and carried his reformation forward

David C. Steinmetz and Paul ThigpenChristian History Timeline: Luther Leads the Way

The century that changed the world

Ken Schurb and the editorsLuther leads the way: Recommended resources

Where should you go to understand Luther and the early Reformation? Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors

The editorsGreat Writings, Did you know?

We asked over 70 past CH authors to help identify the most influential writings from christian history, after the Bible; here are some interesting facts about the 25 writings they named as “greatest"

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate