“¡Llegaron los pentecostales!”

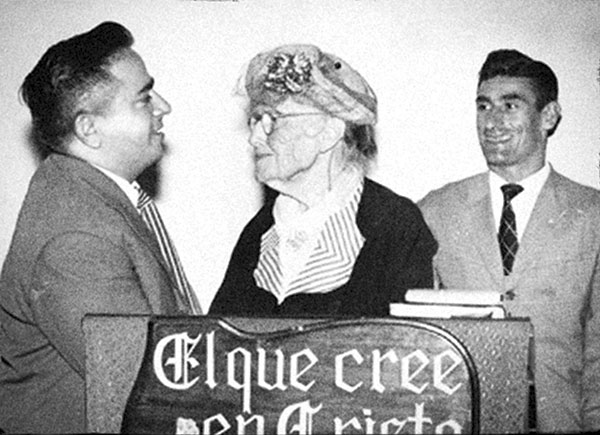

[Church leaders Ernest Diaz (left) and Ruben Ortiz (right) bid farewell to Alice Wood (center), an early North American Pentecostal missionary to Argentina / Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center]

LA HERMANA SONIA (Sister Sonia) was a short, gray-haired laywoman among a group of predominantly male clergy from all over the world, including me. A Pentecostal hailing from Chile, she represented different Pentecostal communities in the Southern Cone of Latin America. The ecumenical and interdenominational conference we were attending addressed issues of worship, seeking answers from a diverse group of worldwide Christian leaders.

The small group meeting began with prayer. La Hermana Sonia stood up and raised her hands and arms to God. Quietly she joined in prayer. Yet it was evident that her embodied prayer caught the attention of some. A Russian Orthodox priest—in a kind, yet authoritative voice—asked Sonia: “Why do Pentecostals raise their hands and arms when praying? Have you considered that such behavior during prayer may distract others from praying?”

She looked puzzled and replied, “I would never want my actions to distract others from prayer and praise to God. We do not raise our hands and arms to call attention. We do it because we are like toddlers seeking to be picked-up and embraced by the tender and loving arms of a parent.” After La Hermana Sonia’s reply, you could hear a pin drop. That evening the priest from the Russian Orthodox Church led worship. Every time the group prayed, he had his hands and arms fully extended to heaven.

The Spirit’s gifts

This story encapsulates the way the Pentecostal movement has influenced worldwide Christianity, particularly in Latin America. Briefly and most generally, Pentecostalism focuses its attention on the gifts of the Holy Spirit—especially, though not limited to, speaking in tongues as evidence of Spirit baptism. Historians often claim that Pentecostalism began in the early 1900s with William Seymour (1870–1922) and the Azusa Street Revival (see CH #58, The Rise of Pentecostalism), but in fact similar revivals arose earlier and in other places, and as time went on, they connected with the generative work of the Azusa Street movement.

The arrival of Pentecostalism in Latin America does not follow a straight cause-and-effect trajectory. Our typical understanding of mission involves missionary work from a Christian region that converts and establishes churches in non-Christian locations; but this pattern is too limited to account for the movement and growth of Pentecostalism worldwide (see “Charity toward all,” pp. 44–47).

Split to grow

In Latin America and the Caribbean, three models came to define emerging Pentecostal work. The first model could be called the noninstitutional split-and- grow model. In this model a noninstitutional missionary feels called to evangelize a region and joins a Protestant church—only to ultimately split from it and establish a new movement with churches under Pentecostal and charismatic experiences.

One example of Pentecostalism spreading in this way is the Congragação Cristã no Brasil (CCB), which began through the ministry of Italian American husband and wife Luigi Francescon (1866–1964) and Rosina Balzano (1875–1953). Originally Presbyterian but influenced by the Azusa Street revival, they left the United States in 1910 to work among Italian immigrants in Latin America, where they established CCB. Although the missionary zeal of Francescon and Balzano began with a concern for the evangelization of Italian immigrants in Brazil, with time they broadened their context for evangelization by shifting from the Italian language to Portuguese.

Dissatisfied with mainline Protestantism and drawn by the charismatic Pentecostal experience, Brazilian Christians flocked to CCB in its early stages. By the 1950s CCB appealed to Brazilians of all ethnic groups. It had also immediately begun training a national Brazilian clergy rather than depending on North American imports to be present to run churches. (Francescon never actually lived in Brazil, although he frequently traveled to the CCB’s various houses of prayer.)

An even more extensive example is what we know today as the Assambléias de Deus (AD) in Brazil, one of the largest denominations in the world. Though currently loosely connected to the Assemblies of God (AG) in the United States, it originated from Swedish missionaries Daniel Berg (1884–1963) and Gunnar Vingren (1879–1933) who, inspired by Azusa Street and called by God to Brazil, began their work in a Baptist congregation.

Berg and Vingren soon grew dissatisfied with the Baptist church and split from the congregation, bringing other dissatisfied mainline Protestants with them. They created a group called the Missão da Fé Apostólica (MFE) in 1911, while keeping an unofficial relationship with the Scandinavian Pentecostal movement. By 1918 they had changed their name to Assambléias de Deus.

The AD complicates the idea of simple cause and effect stemming from North American Pentecostalism. The AG in the United States claimed, and in some cases still claims, to have originated the Brazilian AD. But the AD considers itself an independent and national church. And from the late 1970s until the present, the AD itself has undergone splits and growth creating other small Assambléias denominations in Brazil.

Goodbye, missionaries

Pentecostalism has also spread through the non-institutional missionary to independent church model. In this second model, Pentecostal national churches emerged through noninstitutional missionary work and leadership with no foreign influence. One such example is the Movimiento Misionero Mundial (MMM) in Puerto Rico, catalyzed by the missionary work of Luis M. Ortiz (1918–1996) in the Spanish Caribbean.

A member of a Pentecostal movement called the Iglesia de Dios MI, Ortiz claimed he received his call “by way of different revelations, where visions were simultaneously declared by different sisters and brothers of integrity and in communion” and that “God affirmed a great ministry of global reach.”

Ortiz’s passion for missionary work and fulfilling this mission led him to seek theological formation in the Instituto Mizpa, today the Universidad Pentecostal Mizpa, the oldest Iglesia de Dios MI Pentecostal school in Puerto Rico. In the 1940s he traveled to the Dominican Republic and Cuba where he worked among the poorest people and established non-denominational Pentecostal congregations.

After almost two decades of work, Ortiz returned to Puerto Rico having established many churches—and even more important, having established national leadership to continue the national work. In Cuba, the Iglesia Cristiana Pentecostal (ICP), a national Cuban Pentecostal church with a very loose partnership with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in the United States and Canada, has roots that go back to the missionary work of Ortiz.

When he returned to Puerto Rico in the 1960s, Ortiz founded the MMM. Originally he had not planned on creating a denomination but rather a Pentecostal movement committed to evangelization. Yet Ortiz’s vision for national missionary work in Puerto Rico ultimately established congregations.

The MMM’s Pentecostal congregations were infused with a passion for missionary work in the Spanish-speaking Americas, and by the late twentieth to early twenty-first centuries, local MMM congregations with national leadership had been established all over the world, particularly in Latin America.

Nation to nation

The MMM’s work today exemplifies the third and final model that describes Pentecostal origins in Latin America, which could be called the noninstitutional national to national model. In Latin America as well as around the world, the MMM sends lay missionaries who lack education or US backing. With only prayer support, the leader travels to another country, usually in Latin America, and establishes a congregation, which is quickly put under the leadership of locals.

With time the new MMM congregation is grounded in its context, and the missionary might then be called to another Latin American country to evangelize. The outcome is not always a congregation, as MMM has multiple social ministries connected to evangelization. But the most usual result is a Pentecostal congregation with deep roots in its context that carries the name of an MMM church and is based on its missionary zeal to share the gospel of Jesus Christ. Under this model the MMM has a missionary and congregational presence in almost all of the Latin American and Caribbean countries (some not even taking the MMM identity) and in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Oceania.

The origins of the Latin American Pentecostal movement are as elusive as the wind of the Spirit; they do not follow the missionary cause-and-effect pattern that we are so used to assuming. Just as its movement is elusive, so is its impact in its social, cultural, and political context.

Yet, with very little doubt, it continues to be a Christian expression grounded in a daily-life experience, closest to the poorest of the poor, and often evoking an intimacy with the Spirit that resembles the relationship of a vulnerable toddler with a loving and caring parent. C H

Carlos F. Cardoza-Orlandi is Frederick E. Roach Chair in World Christianity at Baylor University. He is the author of Mission: An Essential Guide and coauthor (with Justo González) of To All Nations, From All Nations, and an ordained minister of the Iglesia Cristiana (Discípulos de Cristo) en Puerto Rico.

By Carlos F. Cardoza-Orlandi

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #130 in 2019]

Carlos F. Cardoza-Orlandi is Frederick E. Roach Chair in World Christianity at Baylor University. He is the author of Mission: An Essential Guide and coauthor (with Justo González) of To All Nations, From All Nations, and an ordained minister of the Iglesia Cristiana (Discípulos de Cristo) en Puerto Rico.Next articles

The delicate balance of church and state in Latin America

The role of religion in Latin America remains strong, and religious voices on all sides can be heard amid current political debates.

Joel Morales CruzSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate