“I shall make all thing well”

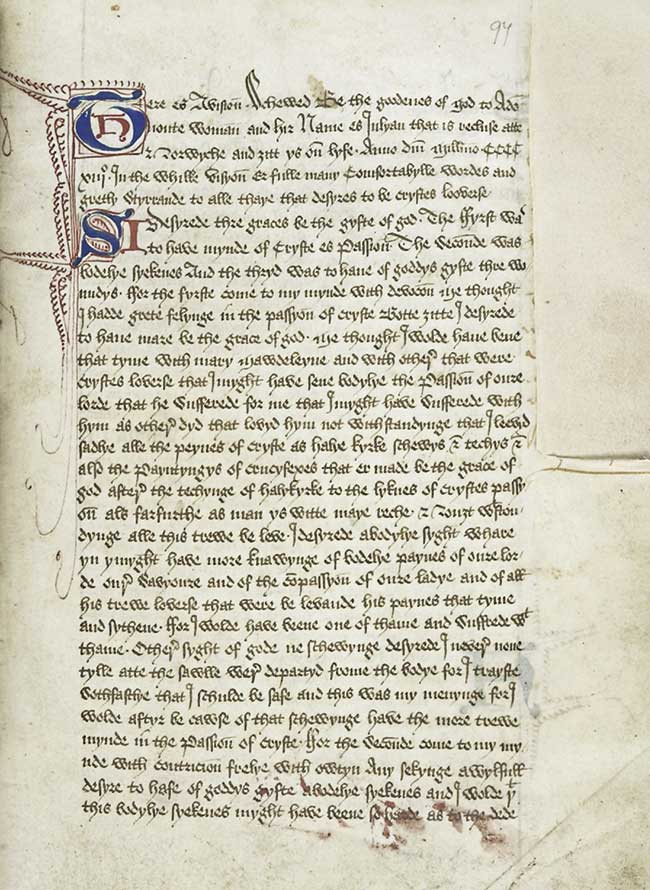

[Richard Rolle, Juliane of Norwich and others, A Carthusian anthology of theological works in English (the “Amherst Manuscript”) Mid-15th century—British Library]

Julian (1374–c. 1416), a notable mystic, was born in Norwich shortly before the Black Death ravaged England. She was about six when the plague swept through Norwich with all its terrors. The frightful cries of misery, the haunting scenes of despair and death, the panic of the populace, and the perplexing mystery of God’s dealings seemed to have turned her thoughts to God’s purposes and her own spiritual inadequacy to face death.

At any rate, sometime in her early years, she felt a lack within herself and asked God for three gifts. The first was the “mind” of Christ’s passion. The second was “bodily sickness in youth at thirty years of age,” by which she meant going through all that a dying person experiences—short of death itself.

The third was to receive three wounds: true contrition, heartfelt compassion, and purposeful love for God. However, she later admitted she had forgotten about the first two requests.

Despite her forgetfulness she considered that God remembered what she had asked because on May 8, 1373, when she was 30, her petitions were granted. She became seriously ill. Everyone thought she was dying. On May 12 she received the last rites, and she continued to decline. Three days later those attending her thought she actually had died. She herself reported difficulty breathing and numbness from the waist down.

A priest came to be with Julian in her final moments. The boy with him held a crucifix before her eyes, then set it at the foot of the bed. The priest commanded her to look at the cross. She did not want to, because it meant she had to change the position of her upper body, which was painful for her. However she obeyed. Soon the numbness spread to her chest and arms, and she could no longer lift her hands. She gasped for air and her heart beat erratically.

All pain was gone

Suddenly, as she stared at the cross, all her pain was gone, and her body was completely whole, especially the upper half. It occurred to her to ask to have Christ’s wounds (the stigmata). In this state of mind, she experienced a vision. She saw blood flow down from under the crown of thorns on the crucifix.

Christ seemed alive on that cross. The Trinity filled her heart with joy. She saw Mary and understood her obedience and reverence for God. And Julian heard Christ speak. He showed her a little thing about the size of a hazelnut and, in answer to her questions, told her it was everything he had made; it would last forever because of his love.

Thus began the first of 15 “shewings,” or revelations, granted her that day, with a sixteenth the following morning. After her recovery she wrote or dictated these visions in short form. For the next 20 years, she mulled them over and teased out their meaning. Finally she wrote a longer text, amplifying the insights she had gained in those years of meditation.

These books are the first known writings of an English woman. Some scholars consider the longer version of the Showings (to use the modern spelling) a work of systematic theology. It is not rigorous scholastic theology with propositions and proofs, but an attempt at eliciting self-consistent answers to theological questions based on what she had seen. She dealt with the origin and nature of sin, God’s love, human predestination, the problem of pain, and other difficulties.

Central to her revelations was the love that drove Christ to suffer for us. She saw this as the whole explanation for history and the great expectation of heaven. When she wondered why God allowed for sin, she merely heard that it was “behovable,” that is, necessary but hinging on other events. Her visionary Christ also promised her that all would be well.

When she wondered how such wellness is possible when the church (based on Scripture) teaches that many souls will be lost, she heard Christ reply, “I shall save my word in all things, and I shall make all thing well.” CH

By Dan Graves

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #135 in 2020]

Dan Graves is layout editor at Christian History. This is adapted from “This Day in Christian History: May 8 —Julian of Norwich and Her Showings”Next articles

Christian History timeline: Plague and epidemic throughout history

Here are some of the most famous epidemics and pandemics that we discuss Christian responses to in this issue

The editorsCourage and pestilence

Luther’s words amid 16th-century plagues speak to our own time in complex ways

Christopher GehrzPlague advice from Martin Luther

We can be sure that God’s punishment has come upon us, not only to chastise us for our sins but also to test our faith and love.

Martin Luther“Christ is the master”

Margaret Blaurer’s life shows how reformers reluctantly made room for female celibate ministry.

Edwin Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate