Courage and pestilence

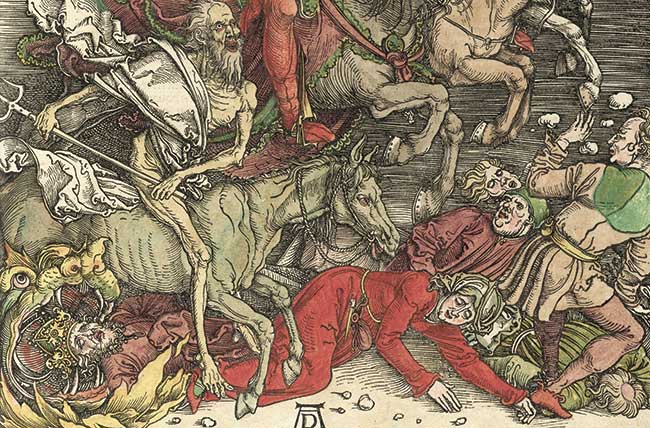

[Detail from Apocalipsis cu[m] figuris, Nuremburg: 1498, by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)—Typ Inc 2121A, Houghton Library, Harvard University / [public domain] Wikimedia]

On August 2, 1527, the bubonic plague returned to the German city of Wittenberg. It had been nearly two centuries since the Black Death, but that dreaded disease had continued to flare up, killing 30 percent or more of the population in each of its periodic outbreaks. Though the students and faculty of Wittenberg were told to leave the city, Martin Luther (1483–1546) stayed put: teaching, preaching, advising the city council, and ministering to the sick.

In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, many Christians have shared quotations from the letter Luther wrote in 1527, Whether One May Flee From a Deadly Plague (see p. 27). While we need historical and theological context to understand why Luther was writing—and what it cost him to stay—his advice is still relevant today.

Significant death

On average Europe saw a significant outbreak of the plague every nine years from the end of the fifteenth century through the middle of the seventeenth. Luther was no stranger to the disease; it had struck the university town of Erfurt in 1505, in the middle of his famous transition from rising law student to troubled Augustinian monk.

The plague intersected often with the history of the Reformation. Eight years before it came to Wittenberg, it killed 1,500 people in the Swiss canton of Zurich, including 22-year-old Andreas Zwingli. His older brother Huldrych (1484–1531), newly called as preacher of the city’s largest church, nearly succumbed himself. Some historians believe the older Zwingli’s brush with death in 1519 helped convince him to bring reform to Switzerland. (It certainly inspired his hymn writing; see p. 29.)

One of Zwingli’s followers in Zurich, Conrad Grebel (c. 1498–1526), had fled an outbreak of the plague in Paris. Over time, however, he broke with his mentor and began to rebaptize adults. With the support of Zwingli, the city council persecuted these early Anabaptists. Grebel managed to escape jail in 1526 and flee to Maienfeld, where another outbreak of plague dealt a final blow to his weakened health.

A year later the same disease took the life of another Anabaptist leader, Hans Denck (c. 1495–1527), who had taken refuge in Basel. In 1541 that same Swiss city would become the final resting place of radical theologian Andreas Karlstadt (1486–1541). His estranged friend Luther would find the cause of death by plague ironic, as he had called Karlstadt “the plague himself of the Basel church.”

Not just Protestants were affected. In 1522 Pope Adrian VI (1459–1523) was inaugurated in the middle of a plague outbreak killing nearly three dozen Romans a day. While all but one of his cardinals fled, Adrian stayed, hoping to bring about a moral and intellectual reformation of the church. He died a year later (not from plague) at age 64; but plague returned during the time of his successor, Clement VII (1478–1534)—even as German soldiers sacked the city and the papal court sheltered in the Castel Sant’Angelo.

That was just a few months before plague hit Wittenberg. When Lutherans fled the disease, a Dominican polemicist used such stories as ammunition in the war of words raging between Catholics and Protestants. So when a fellow Protestant pastor asked for his advice, Luther seized the opportunity to write on “whether one may flee from a deadly plague.”

A test of faith?

Luther acknowledged that how one responded to plague could be viewed as a test of faith in God. He could not “censure” those who stayed in a plague-stricken city, believing that “death is God’s punishment, which he sends upon us for our sins.” Such a view was hardly unusual among Catholics or Protestants of the time. Ten years after Luther’s letter from Wittenberg, plague threatened the city of Nuremberg. That city’s leading Lutheran pastor, Andreas Osiander (1498–1552), preached that “this horrible plague of pestilence cometh out of God’s wrath, because of the despising and transgressing of his godly commandments.”

In 1527 Luther did not doubt the reality of God’s judgments, but he refused to condemn those who tried to escape death. Otherwise, he argued, no one should try to escape a burning house or save themselves from drowning. “Why do you eat and drink,” he continued, “instead of letting yourself be punished until hunger and thirst stop of themselves?” Would such Christians no longer join Jesus in praying that God would “deliver us from evil”?

Even someone so highly educated as Luther did not understand the causes of bubonic plague. But while Osiander warned against attributing epidemics to “natural” causes rather than God’s mysterious judgments, Luther rebuked Christians who make “no use of intelligence or medicine.” Our own medicine is far beyond that of Luther’s day, yet some Christians continue to be wary of the advice of doctors, scientists, and public health officials.

But just as importantly, we should recognize in Luther’s response to the plague his doctrine of Christ-ian vocation. Rather than applying “vocation” primarily to the work of the clergy, Luther argued that God calls all members of the “common priesthood” to specific roles in this world, as particular ways of serving our neighbors in love. Being called to service ran through the whole letter. While it was “natural . . . and not forbidden” to save one’s own life, there was a higher calling to love God and one’s neighbor. It was only “as long as he does not neglect his duty toward his neighbor” that a given person could choose to flee the plague.

Particular callings might require particular courage. Not surprisingly Luther expected health-care workers to continue to care for the body, but he also believed that those called to public office had a high responsibility in the midst of an epidemic:

…all those in public office such as mayors, judges, and the like are under obligation to remain. This, too, is God’s word, which institutes secular authority and commands that town and country be ruled, protected, and preserved, as St. Paul teaches in Romans 13, “The governing authorities are God’s ministers for your own good.”

Though his chief concern here was maintaining social order, Luther also dreamed of a government so efficient that it would maintain places to care for the sick.

Multiple callings

What about pastors? If there were enough clergy to minister to those who remained in the city, others could flee. But Luther stayed. “Those who are engaged in a spiritual ministry,” he reasoned, “must likewise remain steadfast before the peril of death.” But at this point we must recognize a significant tension in Luther’s thought, for he believed that Christian vocation was both particular and plural.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, I too have felt the pull of multiple callings. As a teacher, I’ve moved my classes online. As a historian, I’ve tried to use everything from writing to podcasting to help the public draw on the past to meet the demands of the present. But I’m also a father and a husband, a son and a brother. I’m in a position to serve many, but none need me as much as the members of my family.

So was Martin Luther being faithful to his calling when he continued to teach, preach, and minister in 1527, and wrote this letter that Christians read to this day? Certainly, as a professor, pastor, and preacher. But what about his calling as father and husband?

As much as we can appreciate the wisdom of Luther’s letter, we read it knowing that his decision to stay in Wittenberg exposed his family to plague. While Luther’s year-old son, Hans, recovered from illness and his wife, Katie, survived to deliver their first daughter, young Elisabeth Luther died less than eight months into her life. That tension between multiple vocations runs through the ambivalent judgment of Luther’s recent biographer Lyndal Roper:

Luther’s decision to remain in Wittenberg was bold, but also revealed a reckless disregard for his own safety and that of his family. It may have been a residue of his wish for martyrdom, or, perhaps, another example of the remarkable courage that enabled him not to shirk what he felt to be his responsibility to his flock.

As in Luther’s day, so in ours: we are called in multiple directions as we decide how to respond to COVID-19. Courage may lie down any of the paths we might choose. CH

By Christopher Gehrz

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #135 in 2020]

Christopher Gehrz is professor of history at Bethel University and coauthor of The Pietist Option. He blogs at PietistSchoolman.com and at the Patheos blog Anxious Bench (www.patheos.com/blogs/anxiousbench/), where an earlier version of this article appeared.Next articles

Plague advice from Martin Luther

We can be sure that God’s punishment has come upon us, not only to chastise us for our sins but also to test our faith and love.

Martin Luther“Christ is the master”

Margaret Blaurer’s life shows how reformers reluctantly made room for female celibate ministry.

Edwin Woodruff Tait“Now, Christ, prevail”

When plague struck Zurich, Zwingli hurried home from vacation to tend the sick but soon contracted the disease himself.

ZwingliChrist’s passion and ours

Heerman turned to Christ’s passion to make sense of suffering.

Jennifer Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate