“I would not call it show business”

DURING A 1973 APPEARANCE on the British talk show Russell Harty Plus, Billy Graham described the promise and peril of television ministry.

When Harty asked how Graham’s broadcast evangelism compared to the live preaching of John Wesley, Graham replied, “Television is a medium of face to face communication. It’s the most powerful medium we’ve ever known. And whether you’re selling a bar of soap or whatever you’re doing, television is the way to do it today. And if you are preaching the gospel, you can communicate by television.”

Graham stated that if he appeared on American TV for three nights, he would get 500,000 to 750,000 letters from viewers, “people pouring out their hearts and their problems.” Television could be used for evil, he explained, but it could also be used for good.

Later in the interview, Harty pressed the evangelist to name some pet peeves. Graham admitted that fame grew tiresome. “I’m happy to come to Europe once in a while where I can get a bit more privacy than in America where the television has made [my] face quite well known,” he said. Graham also joked with the host about his own aging countenance. The 55-year-old man on the screen no longer struck Graham as handsome, and he wished for Harty’s “marvelous” hair.

This interview illustrates three aspects of media-molded ministry—one positive, two negative. Graham’s use of media—especially the preeminent medium of the latter twentieth century, television—was extremely effective. But success as a media figure could veer dangerously close to slick salesmanship. Additionally, celebrity took a toll on personal life, demanding large amounts of time and energy from Graham while privileging sound bites over sermons and image over substance.

Testing the media

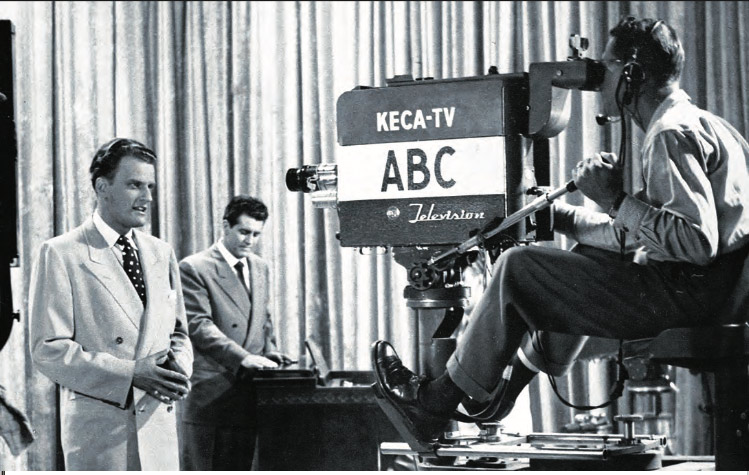

Graham’s career had been linked to mass media ever since newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst (according to a widely circulated legend) instructed his editors to pay attention to Graham during the 1949 Los Angeles crusade. To keep the momentum going, in November 1950 Graham launched the Hour of Decision radio program on 150 ABC stations. Just a few weeks into its run, the weekly broadcast was heard on 1,000 stations, and it topped all other religious programs in the Nielsen ratings. The program was still going under the new name Peace with God in 2014.

Graham experimented with a weekly televised version of Hour of Decision, but he quickly, and wisely, shut it down. Though Graham recognized the unique power of television, regular broadcasts proved both expensive and time consuming. (A constant need for raising funds would later contribute to the televangelist scandals of the 1970s and 1980s.) Graham’s organization opted instead to purchase occasional airtime, mostly to broadcast crusades.

The success of the radio and occasional TV broadcasts led Graham into more media ventures. He launched the My Answer syndicated newspaper column to address recurrent questions from all those who poured their hearts out in letters. He founded World Wide Pictures, a studio whose full-length feature films often followed the narrative of a crusade testimony, complete with footage of Graham preaching. And he started Decision magazine, which also featured crusade testimonies and raised support for evangelism.

One media venture stood apart from the rest: Christianity Today magazine, launched in 1956. Unlike the press and broadcast efforts associated with the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA), the goal of Christianity Today was less to save souls (its early readers were clergy) than to establish evangelicalism as an intellectually worthy religious tradition.

The magazine’s first editor, Carl F. H. Henry, argued for a version of American Protestantism that was conservative on topics like the inerrancy of the Bible and the sovereignty of God but not rigid and reactionary like fundamentalism. Christianity Today put flesh on these bones, fitting in with other Graham-related institutions such as the National Association of Evangelicals and Fuller Seminary.

As even more new media technologies emerged, the BGEA harnessed them to extend the reach of Graham’s evangelism. In 1993, back when the Internet was practically brand new, the 75-year-old Graham participated in an hour-long live chat on America Online. And in 1995, he built on a decade of experimenting with technology, using 30 satellites, 160 digital editing machines, and 13 generators, to transmit services from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to nearly 3,000 sites across the globe in an effort to reach a billion viewers—approximately one-fifth the population of the planet.

Superstar

Vast as it was, Graham’s own universe of print and broadcast media did not encompass the whole of his media engagement. By the early 1970s Graham was a regular guest on mainstream TV talk shows and a frequent contributor to periodicals ranging from Cosmopolitan to National Enquirer. He also gave dozens of press conferences in cities around the world.

In some ways, Graham’s celebrity was another example of how media extended his reach as an evangelist. During a legendary guest spot on Woody Allen’s talk show in 1969, Graham advocated biblical morality as the foundation of a happy life, explained why idolatry is the worst sin, and even evangelized his host. “In God’s sight, you are beautiful,” Graham said. “He made you, Woody Allen, and he expects you to live up to a standard that he has made.” Neither Allen nor his audience heard that kind of a message very often.

Press conferences served evangelistic purposes. Graham typically called a press conference to attract attention to an upcoming crusade. Staff made sure the details of the meeting would appear in the ensuing stories. Reporters allowed themselves to be used for free advertising because Graham fielded questions about current events, and his answers could make headlines.

An exchange from a 1975 press conference in Lubbock, Texas, illustrates Graham’s ability both to use and be used by the media. “You know,” Graham said, “one of the things about being a well-known clergyman or a well-known evangelist is I’m supposed to be an authority on every conceivable subject. And I’m not an authority on many subjects. . . . And there are a lot of the problems that we face today that I haven’t figured out the answer to. Except if everybody would turn to God, everybody would turn to Christ, I think we could approach our problems with new attitudes.”

Having delivered that come-to-Jesus line, Graham proceeded to answer questions about Betty Ford’s views on sex and marijuana, college morality, Watergate, the Equal Rights Amendment, the Middle East, and the American divorce rate. He went on to fill the 48,000-seat Jones Stadium at Texas Tech University for a crusade.

Ministering in the public eye entailed dangers. A remark in an interview could create a firestorm, such as the time in 1975 when a comment taken out of context led to the headline “Billy Graham Backs Ordaining Homosexuals.” He had actually said that homosexuals might be ordained if they repented, accepted Jesus, and were trained. Some reporters left out the parts about repentance and salvation.

Graham’s press team tried to head off such problems by vetting reporters before they got to the evangelist and by cultivating relationships with sympathetic journalists. Even so, press conferences were not tightly scripted, and writers from a variety of perspectives gained access to Graham. Despite his strong objections to the publication, Graham even sat with a reporter for Playboy in 1970, though he demanded that the writer turn off his tape recorder.

Risky business

Graham also constantly ran the risk of the press labeling him a fraud. Following a 1972 documentary about Marjoe Gortner, a phony tent revivalist, reporters repeatedly asked Graham about his own finances and those of other evangelists. Graham reassured the public that the days of the fictional con-man preacher Elmer Gantry were gone, a claim that has, sadly, been refuted many times since he made it—though Graham himself scrupulously avoided financial or sexual scandal.

While he must have faced temptation to put on a show for the camera, or to alter his message for different audiences, Graham’s media engagement was remarkable for its consistency and authenticity. In fact, broadcasting his crusades caused Graham to make his presentation more heartfelt, rather than flashier.

As he said in 1972, “We have no gimmicks because you cannot fool the electronic eye of that camera and people can see whether you’re sincere or not. It is true that our crusades are partially designed because of the cameras. We have to. . . . have excellent personnel who do the singing and the music . . . I suppose in that way we have adapted ourselves to television, but I would not call it show business.” CH

By Elesha Coffman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #111 in 2014]

Elesha Coffman is assistant professor of church history at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary and a former managing editor of Christian History.Next articles

Christian History timeline: life and ministry of Billy Graham

A timeline of world events and the major events in the life of Billy Graham

the editorsThe evangelist and the intellectuals

Billy Graham nurtured intellectual institutions and took the gospel to universities

Andrew FinstuenAn evangelistic band of brothers

Five friends who helped Billy Graham set—and stay—his course

Seth DowlandThe “Modesto Manifesto”

The Graham team decided to take concrete steps to avoid the slightest whiff of controversy

Seth DowlandSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate